American Music Review

Vol. XLVIII, Issue 1, Fall 2018

By Leann Osterkamp, Regis Jesuit High School

Pianists are familiar with Leonard Bernstein’s work Touches for the piano because it is one of the longest works he wrote for the instrument, making it easy to program and present. It also enjoyed public fame as one of the required commissioned works of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, one of the most prestigious competitions for instrumentalists. Some of his other piano works make moderate appearances on stages throughout the world, including his Symphony No. 2, “Age of Anxiety,” which is essentially a piano concerto, and some of his Anniversaries, short vignettes that are often used as encores in most programs. Fewer pianists, however, are even aware of his Sonata for Piano, his longest solo work for the instrument, or the many other short pieces and collections ranging from his Sabras to Bridal Suite. After coming across the Sonata for Piano in my fourth year of conservatory study, I began to question why these terrific works for the piano were not more commonly known and performed. After all, they came from the pencil of Leonard Bernstein. After recording Bernstein’s complete works for solo piano for the Steinway and Sons Label, I made this question the inspiration for my doctoral research.

Bernstein’s piano music is often recycled into his other significant orchestral and theater works. The majority of Bernstein’s piano works are short, often no longer than two or three pages in length, so that, when the music appears in orchestrations, it is always incorporated into a larger musical structure. When recycled, a given piano work is extended, modified, and varied, or, alternatively, the piano score can appear musically identical, serving as an independent scene or episode within the larger instrumental work. As a result, most of the piano works have essentially become musical synecdoches, representing only a part of the more well-known larger whole. Consequently, most are viewed similarly to published sketches or reductions rather than as independent progressive piano works.

The Leonard Bernstein Collection at the Library of Congress houses hundreds of boxes containing letters, photos, manuscripts, receipts, and countless other objects from the life and career of the great maestro. One of the most influential archival scholars for this collection was Jack Gottlieb. In his lifetime, he was the Sherlock Holmes of the piano manuscripts, tracing manuscripts to their respective decade and context. However, in the publication and archival flurry of the twenty-seven years since Bernstein’s death, many piano works were left undated or were inaccurately archived. In many cases, Gottlieb laid an important foundation for understanding the social, historical, and political contexts of many of the piano works but, in his lifetime, was only able to make an initial conjecture about many of their contexts and lineages.

I began my own research at the Library of Congress with a performer’s perspective. I not only wanted to understand when and under what circumstances every piano work was written but I wanted to understand why. As a pianist, I believe that performers are more inclined to connect with and perform repertoire they can see a purpose behind and, in turn, audiences are more receptive to performances of works when they are able to understand the reason behind their creation. Why did Bernstein finish some pieces overnight and spend weeks on others? Why were the Anniversaries dedicated to these specific people and in specific years? Why were there conflicting titles for the Sabras? Why did it appear that there were so many unpublished piano works in the finding aid of the Bernstein Collection that I had never heard of or seen? Why did Bernstein choose to recycle so many of his piano works in larger pieces? These were only a few of the many questions that jumped to mind as I began opening box after box.

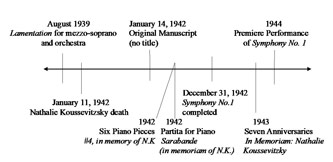

Not only did I find many astounding unpublished piano works within the collection, but as I corrected some dates and pieced together a compositional history, I discovered just how much musicological information was packed into each tiny piano piece. In culmination, the history of the piano works demonstrated clear trends in Bernstein’s compositional process. Individually, each work unveiled a riveting interesting personal side-story that showed the inseparable connection between Bernstein’s personal and professional life. This article will provide a glimpse into how fruitful and illuminating the process of tracing a piano piece backwards from publication to creation can be. The relationships among In Memoriam: Nathalie Koussevitzky; Symphony No. 1, “Jeremiah;” Partita for Piano; Seven Anniversaries; and Lamentation (1939) demonstrate a purpose behind Bernstein’s musical recycling, his compositional process in doing so, as well as the personal and social motivations that influenced his artistic choices.

Though it is common knowledge that the piano work In Memoriam: Nathalie Koussevitzky shares musical material with the “Lamentation” movement from Bernstein’s Symphony No. 1, “Jeremiah,” the accurate compositional dates and circumstances surrounding both works are often incorrect or not present at all.1 The factual historical dates presented here reveal potential issues in publication error and fundamental misunderstandings behind the significance and greater meaning of both works.

Symphony No. 1 was first performed in 1944 with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Bernstein’s original program note unveils the compositional process and timeline of the works while commenting on their external sources for emotional reference and programmatic understanding:

In the summer of 1939 I made a sketch for a “Lamentation” for soprano and orchestra. This sketch lay forgotten for two years, until in the spring of 1942 I began a first movement of a symphony. I then realized that this new movement, and the scherzo that I planned to follow it, made logical concomitants with the “Lamentation.” Thus the symphony came into being, with the “Lamentation” greatly changed, and the soprano supplanted by a mezzo-soprano. The work was finished on 31 December 1942 and is dedicated to my father. … As for programmatic meanings, the intention is again not one of literalness, but of emotional quality. …The movement (“Lamentation”), being a setting of poetic text, is naturally a more literary conception. It is the cry of Jeremiah, as he mourns his beloved Jerusalem, ruined, pillaged, and dishonored after his desperate efforts to save it. The text is from the book of Lamentations.2

Bernstein claims that his initial sketch of Lamentation (1939) was not reused until the spring of 1942. Though Bernstein refers to the work as a sketch in this context, a letter sent from Bernstein to Aaron Copland on 29 August 1939 describes the piece as a finished work:3

I’ve just finished my Hebrew song for mezzo-soprano and orchestra. I think it’s my best score so far (not much choice). It was tremendous fun. Under separate cover, as they say, I’m sending the Lamentation for your dictum. Please look at it sort of carefully, it actually means much to me. Of course, no one will ever sing it, it’s too hard, and who wants to learn all those funny words? Eventually the song will become one of a group, or a movement of a symphony for voice and orchestra, or the opening of a cantata or opera, unless you give a very bad verdict.4

There is a clear distinction between a sketch and an independent work that is part of a larger whole. Furthermore, there is a distinction between a work intended to be part of a larger group and a work that is merely included in a larger collection for the sake of longevity and performance. In this case, Lamentation (1939) was conceived as an independent work that would be used as a part of a larger set merely for likelihood of performance. Lamentation (1939) also was intended for mezzo-soprano initially, meaning this change was not a result of the Symphony No.1, as is suggested by Bernstein’s program note.5

In Memoriam: Nathalie Koussevitzky, which shares a substantial material with the final third movement “Lamentation” of Symphony No.1, was composed on 14 January 1942. This is the new accurate date provided on the manuscript in the Library of Congress. The published version incorrectly labels Nathalie Koussevitzky’s death as 15 January 1942 and the compositional date as 1943. Nathalie actually died on 11 January 1942 and the work was composed in the three days following her death.

This piano work is known today as part of the Seven Anniversaries collection. The published version of Seven Anniversaries was not finalized until around 1943. The Library of Congress collection reveals that the anniversary set went through two significant versions before the final published rendering. One version was a set originally titled Partita for Piano and contained five Baroque dance pieces. In Memoriam: Nathalie Koussevitzky was included in this 1942 set as “Sarabande (in memoriam of N.K.).” In the same year, the piece was included in a set entitled Six Piano Pieces.6

Bernstein needed to finish Symphony No.1 quickly. In 1942, he ended his formal studies at Curtis and moved to New York City to pursue the next chapter of his career. In an effort to help facilitate that process, he decided to submit his Symphony No.1 in a composition competition at the New England Conservatory. Testimony of his close friends and the fact that Bernstein finished the completed work on 31 December 1942 (the final deadline for the competition) prove that there was a significant time crunch imposed on the completion of the symphony:

Bernstein decided to enter his Jeremiah Symphony into a competition organized by the New England Conservatory, for which his Tanglewood conducting mentor Serge Koussevitzky was serving as chairman of the jury. He made significant changes to his song sketch, shifting the vocal part to mezzo-soprano, and in a frantic burst of activity, he worked around the clock to complete the entire symphony before the December 31, 1942 deadline. Bernstein enlisted his sister Shirley and friends David Diamond and David Oppenheim to help with copying and proofreading, and his roommate Edys Merrill hand-delivered the score to Koussevitzky’s Boston home on New Year’s Eve. He did not win the competition, but his Jeremiah Symphony would nonetheless bring him great success.7

Therefore, as Bernstein composed the symphony for the competition, he looked back at earlier compositions to expand and complete a three-movement symphony in the time available. Lamentation (1939) does not include material found in In Memoriam: Nathalie Koussevitzky. The final version of the Symphony No.1 “greatly changed” Lamentation (1939) by simply combining music from Lamentation (1939) with the already completed In Memoriam: Nathalie Koussevitzky. Perhaps Bernstein added the musical material of In Memoriam: Nathalie Koussevitzky to the movement “Lamentation” to not only save time, but to also catch the emotional attention of Maestro Koussevitzky.8 It is interesting to consider whether the repurposing of his piano music was solely done out of time constraints, for social favoritism, or a perfect combination of both.

In comparing these manuscripts and all other examples of Bernstein’s repurposing of early piano music into later orchestral manifestations, a clear compositional trend appears. Articulation and phrasing are modified during the repurposing but the musical structure and original content are maintained from the piano score. This trend gives a fresh insight into Bernstein’s compositional process and personal perspective of his piano repertoire.

A short two-page solo piano piece can tell performers and scholars many different stories about this iconic composer. Alone, In Memoriam: Nathalie Koussevitzky demonstrates beautiful lyricism for the piano and shows a personal connection to the Koussevitzky family. Historically, it illuminates the young maestro’s life events of the time and leads to the discovery of lost collections, such as Partita for Piano. Compositionally, it is one of Bernstein’s earliest examples of musical recycling and helps to create the foundation for one of his most significant compositional trends, as well as highlight some facets of his orchestration techniques (when compared to the later repurposing). Musically, it also changes current performance practice for pianists. As I recorded this work for my album, it was invaluable to understand that the piece was conceived as a sarabande, which influenced phrasing, pacing, and rhythmic stress. Bernstein’s piano music is a fresh new portal into understanding the maestro as a composer and a social icon.

Notes

- 1 A representation of this is the work of Sigrid Luther, “The Anniversaries for Solo Piano by Leonard Bernstein,” (DMA diss., Louisiana State University, 1986). Not only is the death date of Nathalie misrepresented, but the order of compositional manifestations is merely hypothesized.

- 2 Leonard Bernstein, Program Note to Symphony No. 1, “Jeremiah” (1942), (Milwaukee: Boosey & Hawkes, 1992).

- 3 The completion date on the manuscript reads August 25, 1939.

- 4 Leonard Bernstein to Aaron Copland, 29 August 1939, in The Leonard Bernstein Letters, ed. Nigel Simeone (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 35.

- 5 Leann Osterkamp, “Leonard Bernstein’s Piano Music: A Comparative Study of Selected Works (DMA diss., The Graduate Center CUNY, 2018), 28.

- 6 Though it is clear that the January 14 manuscript is the initial manifestation of this specific piano work, it is uncertain whether Partita for Piano or Six Piano Pieces came first. The edits on Six Piano Pieces may indicate that it is the earlier of the collections.

- 7 Leonard Bernstein Office, “Symphony No.1: Jeremiah (1942),” accessed 7 June 2017, https://leonardbernstein.com/works/view/4/symphony-no-1-jeremiah.

- 8 Osterkamp, “Leonard Bernstein’s Piano Music,” 30.