American Music Review

Vol. XLVIII, Issue 1, Fall 2018

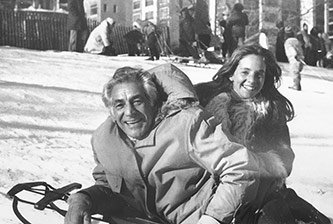

By Jamie Bernstein

From the time he was a young man, my father spoke out whenever he saw an injustice, or an atrocity, or a dire need. It often got him into trouble. Indeed, by the time he was able to view his own FBI file in the 1980s, it was 800 pages long. That’s because J. Edgar Hoover had been keeping tabs on that pesky Bernstein guy since the 1940s. But that was my father’s way: he didn’t shrink from raising his voice in protest when he thought it was necessary to speak up.

And whenever he could, he put his own music to work to express the ideas he believed in. Many of his compositions explore humanity’s struggle to rise above evil.

My father never lost his idealism; there was a part of him that felt if he could just write a good enough melody, he might be able to heal the world. Of course, he knew this was impossible; he wasn’t crazy. But the impulse to make the world a better place through his notes drove him forward as a composer. What I hear in my father’s music—and what moves me the most—is that he could not and would not give up on the possibility of a better world. In fact he’s dreaming that world for us, through his notes.

That dream drove him forward as a conductor, too. On 24 November 1963, he conducted Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, “Resurrection,” in a televised tribute to President Kennedy, who had been assassinated two days earlier. On the broadcast my father said, “This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.” I see that quote all too often these days; it’s a social media favorite every time there’s a terrorist incident, or a school shooting.

During the Vietnam War, my father composed his theater piece Mass, which channeled the angry protests of the young people in those days who were confronting a bellicose and irresponsible government. The piece was commissioned for the inauguration of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. President Nixon was advised against attending the event; his henchmen warned that Bernstein had inserted a “secret message” in Latin to embarrass the president. The secret message turned out to be “Dona nobis pacem”—a standard line in the Catholic liturgy. It was a typical moment of Nixon administration paranoia. But in any case, there was certainly nothing secret about my father’s anti-war stance; that’s one of the reasons Leonard Bernstein’s name appeared on Nixon’s infamous White House Enemies List.

Leonard Bernstein lived long enough to witness the Soviet Union lose its iron grip on eastern Europe and to see the Berlin Wall come down. On Christmas Day of 1989, my father conducted a multinational orchestra, chorus, and soloists in a historic performance of Beethoven’s 9th, broadcast worldwide from the newly reunified city of Berlin. For the occasion, my father changed Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” text to “Ode to Freedom.” The event was a magnificent expression, in my father’s final year, of his lifelong commitment to using music as an engine for peace, compassion, and brotherhood—the very same goals that Beethoven himself strove to express through his own symphonies.

All my father’s words, deeds, and ways of living provide a shining example to young artists today—musicians in particular—who are newly galvanized to forgo the ivory tower and, instead, share their creativity with their communities and reach out with their artistry to help make the world a better place. These young people refer to themselves as Citizen Artists. It’s a beautiful name for a beautiful way to be— and without a doubt, Leonard Bernstein was Citizen Artist Number One.

He put his music-making to greater purpose whenever he could. We think of that Beethoven 9th at the fall of the Berlin Wall; we think of the songs reflecting feminism, civil rights, and gay rights within his piece Songfest; we think of his theatre piece Mass, which protested the Vietnam War; we think of his Journey for Peace concert in Hiroshima, and his Music for Life concerts to benefit AIDS research.

In the myriad celebrations for Bernstein at 100, we’re not just looking backward; we’re contemplating the future. This is where music is going: music in the service of others, music to heal an ailing planet, music to raise hope and neutralize hatred, music as a manifestation of love. These are the ingredients of my father’s unique legacy. His 100th birthday is a wonderful opportunity for orchestras, soloists, teachers, and music fans of every stripe to celebrate Leonard Bernstein, not only as the iconic twentieth century composer that he was, but also as a template for the passionate—and compassionate—musician of the twenty-first century.