American Music Review

Vol. XLVIII, Issue 1, Fall 2018

By Kathy Acosta Zavala, University of Arizona

You see, you’ve got to work fast, but not be in a hurry. You’ve got to be patient, but not be passive. You’ve got to recognize the hope that exists in you, but not let impatience turn it into despair. Does that sound like double-talk? Well, it is, because the paradox exists. And out of this paradox you have to produce the brilliant synthesis. We’ll help you as much as we can—that’s why we’re here—but it is you who must produce it, with your new atomic minds, your flaming angry hope, and your secret weapon of art. (399)

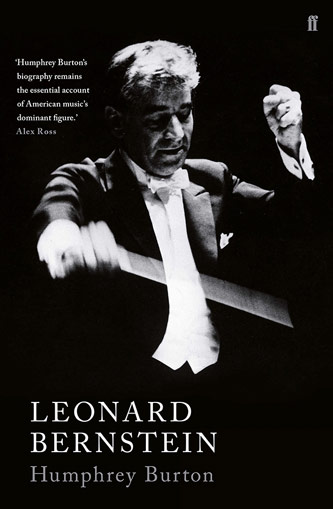

Bernstein delivered this speech in 1970 for the opening day at Tanglewood. In hindsight, the sentiments echoed a life dedicated to teaching the next generations of musicians around the world. On the centenary of Leonard Bernstein’s birth, the musical world has decided to pay tribute to this American icon and remember him with nothing short of a Bernstein bash. His music has been the main focus of festivals around the world. His Sony recordings have been presented as Bernstein’s Mahler Marathon at Lincoln Center. And works by scholars, biographers. and writers—including his eldest daughter, Jamie Bernstein’s Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein (Harper, 2018)—have taken on the task of revisiting his life, accomplishments, struggles and, most importantly, his legacy. Humphrey Burton’s revision of his 1994 biography, Leonard Bernstein (Faber & Faber, 2017), is part of this celebration, providing invaluable insights into Bernstein’s life, struggles, rise to stardom, and personal life.

Burton’s biography is a massive undertaking of love and dedication. Throughout the chronological format of the biography he allows the reader to develop a personal rapport with Bernstein through writings, lectures, and interviews. In addition Burton includes extensive letters to close friends and musical contemporaries, such as the conductors Mitropoulos and Koussevitzky, the composers Aaron Copland and David Diamond, and others. In the book, the letters to Helen Coates, who was Bernstein’s teacher, personal secretary, and confidant for more than fifty years, are essential to the overall understanding of Bernstein’s struggles, thoughts, sexuality, relationships, and musical projects. Newspaper articles, reviews, and Bernstein’s speeches are also used to construct a compelling narrative.

Burton’s tone, at times ironic and comical, allows the author’s voice to come through and hints at his opinions and perceptions. Comments such as “he had only himself to blame for his spreading waistline” (428) and parenthetical additions such as “in Vienna he conducted Mahler’s Sixth Symphony, which made a fine (but bearded) conclusion to Unitel’s Mahler cycle,” (437) punctuate Burton’s narrative persona.

The biography begins with an almost theatrical prologue that describes Bernstein’s funeral: “Everything was orderly and quiet. It made a startling contrast with the jagged tensions of the funeral parlor scene Bernstein had imagined for the opening of his opera A Quiet Place.” (xiii) After the opening, the book is formatted in six carefully delineated parts. In “Part One—The Education of an American Musician: 1918–1943,” Burton is not shy in pointing out Bernstein’s inconsistent and misguided statements about his childhood and teen years during interviews later in his life. For instance, Burton points out that Roy Harris, rather than Koussevitzky, was the first to suggest that Bernstein change his name to something more Anglo-Saxon when he was inquiring about studying at Curtis at Copland’s suggestion.

In “Part Two—Rise to Prominence: 1943–1951,” the biography becomes a valuable resource for study of Bernstein’s compositional output. Each composition is contextually set into the narrative allowing the reader to become acquainted with extra-musical factors. Part Two, “Part Three—Something’s Coming—The Composing Years: 1952–1957” and “Part Four—The New York Philharmonic Era: 1957–1969” follow the young conductor’s travels across the continent, and later the world. His first encounter with Felicia Montealegre in February 1946, their almost five-year-long engagement, and their marriage and Bernstein’s entrance into the world of fatherhood are chronicled. It is during these chapters that we start to comprehend two main contradictions in Bernstein’s life: a desire to be a conservative family man that conflicted with his addiction to traveling and the baton; and the tension with what Burton calls “his alternative life” as a composer and the conundrum of never allocating enough time to compose, always struggling to finish compositional projects and commissions, and leaving his works to the mercy of his incredibly busy schedule. Comments such as “Bernstein remained as hooked on the baton as he was on nicotine” (462) permeate the last two parts of the book, “Part Five—Coming Apart: 1969-1978” and “Part Six—Anything but Twilight: 1978–1990.” Bernstein’s celebrity status in the press, Felicia’s death, his coming out as gay, his deteriorating health, and his desire to lend support to nuclear disarmament and world peace come through in these last chapters as well. Burton describes how Bernstein’s early worries from 1947 that “his work as a composer might forever be sacrificed on the conductor’s altar” (155) became a driving force to establish a legacy beyond his conducting and resulted in the composition of his American opera A Quiet Place, which took him thirty-five years.

Burton’s 2017 revised edition contains a “New Introduction,” which discusses new scholarship written about Bernstein in the twenty-first century. The topical divisions include Bernstein’s early music-making, his Harvard years, the early years in New York, his homosexuality, early ballets, his Broadway production in the time of war, the FBI surveillance period, the New York Philharmonic years, the legacy of the Young People’s Concerts, and the 2013 publication of “Mr. [Nigel] Simeone’s . . . scrupulously edited The Leonard Bernstein Letters.” (3)

Burton’s biography made me reflect on the personal correspondence that came to light in The Leonard Bernstein Letters addressing Bernstein’s sexuality. The Felicia Bernstein letter, which has been labeled as ranking amongst “the most thoughtful and touching ‘prenuptial agreements’ on record” dating 1951–1952, became one of the most revealing sources in unveiling Felicia’s understanding and acknowledgement of the maestro’s homosexuality.1 In it is she says, “You are a homosexual and may never change—you don’t admit to the possibility of a double life, but if your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depend on a certain sexual pattern what can you do?”2 Another scholarly source addressing Bernstein’s sexuality is Nadine Hubb’s article titled “Bernstein, Homosexuality, Historiography.”3 After reading these articles and letters, I wonder whether the inclusion of these new findings and perspectives could have changed the narrative in Burton’s biography.

The technological advances of the twenty-first century have magnified the online resources available for further scholarship on Bernstein’s life. Scholars now have access to the Library of Congress Leonard Bernstein Collection and the New York Philharmonic Archives at the touch of a button. Burton’s appendix “Notes to Sources” has retained its value by providing Bernstein scholars with an encyclopedic compendium of quotes from letters, interviews, reviews, and Bernstein’s professional writings. This appendix can be considered a companion to the cornucopia of letters, concert programs, reviews, and writings available online. Combined with all the new research on Bernstein, Burton’s Leonard Bernstein has evolved from an essential biographical source to a key resource in the study of twentieth-century American music.

Notes

- 1 Michael Roddy, “Bernstein in Letters: Gifted, Gay and Loved by his Wife,” Reuters (11 April 2014).

- 2 Nigel Simeone, ed. The Leonard Bernstein Letters (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013).

- 3 Nadine Hubbs, “Bernstein, Homosexuality, Historiography,” Women & Music, 13 (2009): 24–42.