American Music Review

Vol. XLV, No. 1, Fall 2015

By Carolyn Guzski, SUNY—College at Buffalo

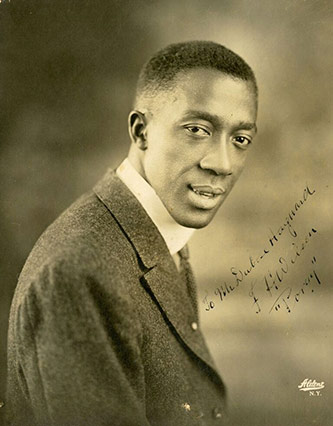

Frank H. Wilson, Courtesy South Carolina Historical Society, DuBose Heyward Collection.

The bracing sounds of Machine Age modernism juxtaposed with the gestures of symphonic jazz reached the stage of the Metropolitan Opera at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, when John Alden Carpenter’s ballet Skyscrapers was given its world premiere by the theater’s resident dance company and orchestra on 19 February 1926. An unusual number of debuts were made on the highly anticipated evening: Carpenter (1876-1951), already well known in the genre for his scores to The Birthday of the Infanta and Krazy Kat; Robert Edmond Jones (1887-1954) as designer and co-creator of the abstract staging; corps member Roger Pryor Dodge (1898-1974), later an exponent of jazz dance, in a principal role; and musical theater choreographer Sammy Lee [Samuel Levy] (1890-1968) as director. The Metropolitan departed most significantly from tradition, however, by including an unprecedented program credit for a special all-black chorus employed in the ballet’s central “Negro Scene” and identifying its leader, Frank Wilson, by name.1

New York’s leading African American newspaper, the New York Amsterdam News, congratulated the performers on the putatively historic occasion: “This will be the first time, to our knowledge, that our people ever had the opportunity of appearing at the Metropolitan and it is natural that we should wish all hands luck in this new undertaking.” The uncertainty was well founded, for Pitts Sanborn of the New York Globe had been the city’s sole daily arts critic to call attention to an earlier cohort of dancers of color who appeared as supernumeraries in the 1918 Metropolitan premiere of Henry F. Gilbert’s The Dance in Place Congo, noting: “The few real Negroes on the stage were worth many times all the host of disguised whites.”2 Wilson’s achievement was buried as well across succeeding decades—race is not promoted in a World War II-era house publication, Metropolitan Opera Milestones, and Wilson himself is absent from the theater’s inaugural annals, only to resurface in an exhaustively revised edition without the debut attribution accorded his colleagues on the Skyscrapers production team.3 He receives cryptic mention in a profile of the theater’s historical archives and a scholarly biography of Carpenter. But not until Carol Oja’s Making Music Modern connected the dots with James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan was the performer identified as the actor singer Frank H. Wilson (c. 1885-1956), creator of the title role in the 1927 dramatization of DuBose Heyward’s novel Porgy, as well as a featured role (developed for him by Heyward) opposite Paul Robeson in the film adaptation of The Emperor Jones (1933).4 While Wilson’s papers are regrettably not extant, newly available resources offer an expanded perspective on the circumstances surrounding a stage debut that preceded by nearly three decades that of Marian Anderson, complicating the received narrative of the theater’s official desegregation in 1955.5

It was Otto H. Kahn (1867-1934), the progressive-minded chair of the Metropolitan production company from 1908, who issued a call to arms for American contemporary realism at the opera in 1924 with the startling suggestion that Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, and George Gershwin write for the Met’s stage.6 Kahn had charged assistant general manager Edward Ziegler with seeking fresh talent for an American repertoire program initiated under his aegis in 1910, and the former music critic placed Carpenter on his roster of composers to pursue. Kahn attempted to interest Carpenter in rising playwright Zoë Akins as librettist, but without success. The composer instead sought European production of his Infanta score with the famed Ballets Russes, using a connection with Sergey Prokofiev (Carpenter helped push The Love for Three Oranges to production in his native Chicago) to have the composer advocate for his music with company director Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929) in Paris.7 Notably cool to American work for its purported lack of sophistication, the impresario declined Infanta but unexpectedly advanced an unrealized concept—attributed to his former dancer-choreographer Leonid Massine (1896-1979)—on the theme of the chaotically energetic American metropolis. Artistic representation of contemporary life through the dance had emerged as a hallmark of the newly formed Ballets Suédois, and Diaghilev viewed the competitive threat posed by the company’s performances at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées with increasing concern.8

Carpenter responded with an adroit twenty-five-minute dance score. Its single act was structured as a chiastic arch in five sections that even an envious Prokofiev admitted was “[M]odernistic and admirably orchestrated,” albeit “empty, with snatches of Petrushka and of the French composers,” an opinion he rendered after hearing the Metropolitan dress rehearsal.9 Skyscrapers: A Ballet of Modern American Life portrayed a reinvigorated interwar generation against the dramatic backdrop of a second Industrial Age, drawing in part on a contemporary aesthetic vision that explored interrelationships among African and African American influences on the modernist scene. The idea had already found expression in the Ballets Suédois repertoire (the troupe gave the 1923 world premiere of Milhaud’s La création du monde), perhaps inspiring Carpenter’s pursuit of similar creative elements as the Skyscrapers project coalesced. His own strategy was distinctly reactionary, however, possibly in response to the tepid reception of the Milhaud work in America (blamed on its ultramodernist idiom) and the Met’s conservative reputation.10

Carpenter’s “Negro Scene” is set as a sonic oasis amid the sweeping vitality of “Work” and “Play,” components of American life depicted with Stravinskyan rhythmic propulsion, neoprimitivist melodies, bitonal harmonic collisions, and a striking orchestration featuring multiple pianos (a legacy of Les Noces), prominent brass and woodwind groups, and a colorful percussion battery. It is in the ballet’s central section, where the Negro Scene follows the departure of revelers from a Coney Island landscape, that Carpenter most decisively positions his music as an entry in the symphonic jazz genre by augmenting allusions to ragtime and popular song, and the novelty timbres of banjo and a saxophone trio, heard earlier.11 The “Negro Scene” itself originates as a dream sequence for an African American character (portrayed at the Met by Dodge) costumed in the regulation street-cleaning uniform of New York’s municipal White Wings brigade. Carpenter’s orchestration shifts to richly textured string writing to introduce a gentle blues-inflected melody that is subsequently set to vocables (sung at the Met by Wilson and his chorus). The composer overtly sought a “throw-back to negro plantation life” through the evocation of the African American spiritual, which transitions in the scene’s second half to a fervent jubilee-inspired idiom both sung and danced by the chorus as they symbolically join White Wings in the modern age.12

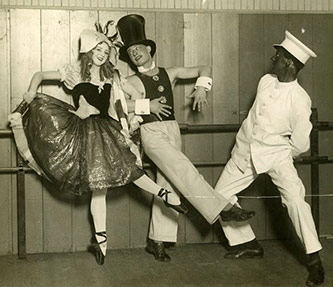

While the sequence’s patronizing images and romanticized view of a halcyon antebellum South are certainly problematic for modern audiences, Carpenter evidently believed its vocal forces were vital, for he was extremely reluctant to omit them at Diaghilev’s request.13 In the event, the impresario lost interest in the work after a projected Met-sponsored American tour by his company was abandoned, and Metropolitan general manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza subsequently acquired the piece, assuring Kahn that the 1925-26 season would “have a varied and interesting repertoire and in a greater part of a modern character [sic].” Gatti recognized that Carpenter “wrote [Skyscrapers] without having a real libretto and I must frankly admit that it will not be easy to find a plot or a series of scenic impressions to fit it. However, we shall do our utmost so that the Ballet may be presented in an interesting manner.”14 The laborious task was accomplished by the composer in collaboration with Robert Edmond Jones, whose distinguished New Stagecraft work with Eugene O’Neill, as well as his design and direction of Ridgely Torrence’s landmark Three Plays for a Negro Theater (1917), were well known to Kahn. On retreat in rural Vermont, the pair devised a principal dance trio comprised of a Broadway entertainer (the “Strutter”) and an “American Girl” ingenue (played by prima ballerina Rita De Leporte as “Herself”)—character types that had appeared in Cole Porter and Gerald Murphy’s 1923 ballet Within the Quota—in addition to White Wings. By August 1925, however, Ziegler was complaining to Kahn of Carpenter’s “intrusive manner” with respect to the production’s staging and casting. Whether racial considerations were under debate is unclear, but in December Frank Wilson signed a Metropolitan contract to “furnish ... Twelve (12) Colored Singers to sing the music allotted to them in Mr. John Alden Carpenter’s Ballet ‘Skyscrapers’” at a fee of $120 per performance for the group, inclusive of all rehearsals.15 Any friction surrounding the engagement was likely to have been diplomatically resolved by Kahn, whose steady support also lay behind the 1918 Place Congo production.

Skyscrapers principals Rita De Leporte, Albert Troy, and Roger Pryor Dodge, Courtesy Pryor Dodge.

Wilson pursued serious aspirations throughout the Harlem Renaissance period as a dramatic actor, still a rarity among black performers severely limited by casting opportunities. Born Francis Henry Wilson, the actor endured an early life unsettled by his widowed mother’s premature death from asthma in the overcrowded tenements of San Juan Hill (later the setting for West Side Story).16 Wilson joined the legions of African Americans consigned to grueling service work in the city before finding a new home among the family of actress Ann Greene. The couple married in 1907 at St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church on West 53rd Street, a center of black life for its proximity to several prominent congregations, the Colored Men’s Branch of the YMCA, and especially the Marshall Hotel, epicenter of black Bohemia and the African American entertainment industry. Wilson demonstrated a fine singing voice on the vaudeville stage, touring with blackface minstrel Eddie Leonard and forming the Carolina Comedy Four vocal quartet, before delving into acting at Harlem’s Lincoln and Lafayette theaters in his own plays of black life. The productions were frequently accompanied by a spirituals ensemble known as the Folk Song Singers, which he organized.17

In 1917 Wilson embarked on a course of study that would change his life when he enrolled at the American Academy of Dramatic Art along with Rose McClendon (1884-1936), a completely unknown artist destined to become the leading black actress of her generation. Both in their thirties at the time of their dramatic debuts, the pair appeared jointly in a number of increasingly visible New York productions: Justice (1919); In Abraham’s Bosom (Pulitzer Prize, 1927), Wilson’s breakthrough role, taken over from Jules Bledsoe at the Provincetown Playhouse one month after the conclusion of his Skyscrapers engagement; and Porgy (1927-1930), in which the actor logged 853 performances in the title role, including a European tour and command performance for George V.18 Given his arduous path to success, Wilson’s reputation as man and artist is remarkable. Joining the Broadway cast of Watch on the Rhine in 1941 (Wilson appeared in both the stage and film versions), actress Ann Blyth encountered the actor as a supportive presence backstage and consummate professional. A young family member remembered him as exceptionally modest, yet highly aspirational: “He really encouraged us to make something of our lives.”19

Wilson undoubtedly struggled with the pervasive racial inequities of the legitimate stage, which the Metropolitan reinforced by casting the sole featured black role in Skyscrapers with a white dancer. This common industry practice continued to rob performers of color of the few roles to which they may have been able to gain access. Yet the garish blackface makeup worn by the White Wings character in publicity photographs, redolent of Al Jolson’s in The Jazz Singer (1927), differs markedly from an alternate view (above) that was not released by the theater, in which Dodge attempts a visual portrayal without resort to obvious minstrel style. It is difficult to determine which version found its way to the Met stage, but a photograph of the Place Congo company indicates that in 1918 the theater followed a version of intricate racial coding that arose in early film productions to maneuver among performative conventions in flux: performers of color were portrayed with visual authenticity (albeit in stereotyped roles); principal dancers (all white, and identified in the program) wore ethnic makeup similar to Dodge’s in the unreleased photograph; and corps men (all white, and by Met tradition not listed in the program) who portrayed black characters partnering women used minstrel-style blackface. The stratagem served to signal—rather than conceal—white male identities among the corps, differentiating them from actual performers of color in order to ostensibly quell audience anxieties surrounding the possibility of unsanctioned interracial intimacy. Some metropolitan journalists wrote dismissively of the relevance of such purported “morals issues” to artistic organizations, but fears of public protest were apparently not entirely unfounded, for during its 1916 American tour the Ballets Russes management was summoned before Manhattan’s chief magistrate to explain the behavior of “carousing slaves” in the harem scene of its staging of Scheherazade. Only “by urging upon the negro slaves the desirability of respectful demeanor toward the houris” was the troupe allowed to retain the ballet in its Met-sponsored engagements.20

While critical response to the world premiere of Skyscrapers was generally positive, with the “Negro Scene” uniformly praised, the Metropolitan’s attempt to remain culturally relevant in the American imaginary dated rapidly and Skyscrapers was dropped from its repertory by 1930. By then, however, Wilson’s dramatic career was fairly launched, and the realpolitik of representing the nation’s shifting racial terrain on the lyric stage awaited renegotiation.

Notes

- 1 Skyscrapers program (season 1925-1926), Metropolitan Opera Archives, Lincoln Center, New York.

- 2 “American Ballet by Negroes at Opera House,” New York Amsterdam News, 17 February 1926, 5; Sanborn, “American Pieces Produced at the Metropolitan,” New York Globe, 25 March 1918, 10.

- 3 Mary Ellis Peltz, Metropolitan Opera Milestones (New York: Metropolitan Opera Guild, 1944); William H. Seltsam, comp., Metropolitan Opera Annals: A Chronicle of Artists and Performances (New York: H.W. Wilson and Metropolitan Opera Guild, 1947), 444; Gerald Fitzgerald, ed., Annals of the Metropolitan Opera: The Complete Chronicle of Performances and Artists (New York: Metropolitan Opera Guild and Boston: G.K. Hall, 1989), updated version available online as http://archives.metoperafamily.org/archives/frame.htm.

- 4 Dorle J. Soria, “Treasures and Trifles,” Opera News 52 (September 1987): 26; Howard Pollack, Skyscraper Lullaby: The Life and Music of John Alden Carpenter (Washington, D.C. and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995; rprt. as John Alden Carpenter: A Chicago Composer, Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2001), 223; Carol J. Oja, Making Music Modern: New York in the 1920s (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); James Weldon Johnson, Black Manhattan (New York: Knopf, 1930).

- 5 Interview with Carlotta Wilson Stanley (Brodheadsville, Penn.), 27 June 2014.

- 6 “The Metropolitan Opera: A Statement by Otto H. Kahn” (New York: Metropolitan Opera Company, 15 October 1925), 22-23; Otto H. Kahn Papers, Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library, Princeton, N.J., box 171. The contents of this pamphlet were largely drawn from a speech Kahn delivered on 1 January 1924.

- 7 Carpenter letter to Ziegler, 21 October 1919, Metropolitan Opera Archives, Ziegler correspondence (season 1919-20); Sergey Prokofiev, Diaries 1915-1923: Behind the Mask, trans. Anthony Phillips (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008), 516.

- 8 Carolyn Watts, “America in the Transatlantic Imagination: The Ballets Russes and John Alden Carpenter’s Skyscrapers” (M.A. thesis, University of Ottawa, 2015), 20-21, 52.

- 9 Sergey Prokofiev, Diaries 1924-1933: Prodigal Son, trans. Anthony Phillips (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012), 270-71. Prokofiev negotiated unsuccessfully with the Metropolitan during his American period for the production of three of his operas: The Love for Three Oranges, The Gambler, and The Fiery Angel.

- 10 Watts, “America in the Transatlantic Imagination,” 21-23. The shift in appreciation of African art from ethnographic record to aesthetic object in New York dates from 1914 exhibitions at the Washington Square Gallery, curated by Robert J. Coady, and at Alfred Stieglitz’s Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession. “African Art, New York, and the Avant Garde,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2012/african-art/appreciation-for-african-art.

- 11 A detailed discussion of the score and associated staging appears in Pollack, Skyscraper Lullaby, 222-34. The concept of symphonic jazz was set in motion by the pioneering Carnegie Hall appearances (1912-1914) of African American conductor James Reese Europe (1880-1919) with the Clef Club Orchestra and promoted after his death by self-proclaimed “jazz missionary” Paul Whiteman (1890-1967), who premiered Carpenter’s A Little Bit of Jazz at his Second Experiment in Modern Music concert at Carnegie Hall in December 1925. The style had already been heard at the Metropolitan in 1924 when competing bandleader Vincent Lopez appeared at the house on a rental basis with a program that significantly featured a multiracial roster of composers. See Oja, Making Music Modern, 326-27.

- 12 Carpenter’s scenario sketches, quoted in Pollack, Skyscraper Lullaby, 232-33.

- 13 Financial strictures were cited as the primary reason; Watts, “America in the Transatlantic Imagination,” 84-85.

- 14 Gatti-Casazza letter to Kahn, 26 May 1925, Metropolitan Opera Archives, Gatti-Casazza correspondence (season 1925-26).

- 15 M.L. [Minna Lederman], “Skyscrapers: An Experiment in Design,” Modern Music 3 (January-February 1926): 25; Ziegler letter to Kahn, 12 August 1925, Kahn Papers, box 171; F.H. Wilson contract with Metropolitan Opera Company, 24 December 1925, Metropolitan Opera Archives.

- 16 Certificate of Death, Phebe Wilkinson Wilson (M10468, 4 April 1897), New York City Department of Records, Municipal Archives. Wilson’s birth certificate remains unlocated, but the actor gave his birth date as 4 May 1885 on WWI and WWII draft registration documents. This date is also recorded on his Certificate of Death (Borough of Queens, 156-56-401783, 17 February 1956), and comports with the age reported on the certificate of his first marriage (M15470, 12 June 1907).

- 17 Marcy S. Sacks, Before Harlem: The Black Experience in New York City before World War I (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 6, 76-77; “Famous Neighbors,” Long Island Sunday Press, 14 February 1937, 2; “‘Pa Williams Gal’” is Well Received at Lafayette Theatre,” New York Age, 15 September 1923, 6.

- 18 Wilson letter to DuBose Heyward, 3 February 1930, Heyward Collection 1172.01.04.03 (P) 1-18, South Carolina Historical Society, Charleston. Wilson also had supporting roles in prominent O’Neill plays of the 1920s: All God’s Chillun Got Wings (1924); and The Dreamy Kid/The Emperor Jones (double bill, 1925).

- 19 Telephone interviews with Ann Blyth (Toluca Lake, California), 13 May 2015; and Eula Gunther Evans (Petrolia, Ontario), 13 July 2014.

- 20 “Tailoring of Police Spoils ‘Scheherazade,’” New York Tribune, 27 January 1916, 9. A detailed historical discussion of racial coding appears in Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, Migrating to the Movies: Cinema and Black Urban Modernity (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005), 50-90.