American Music Review

Vol. XLV, No. 1, Fall 2015

By Stephanie Doktor, University of Virginia

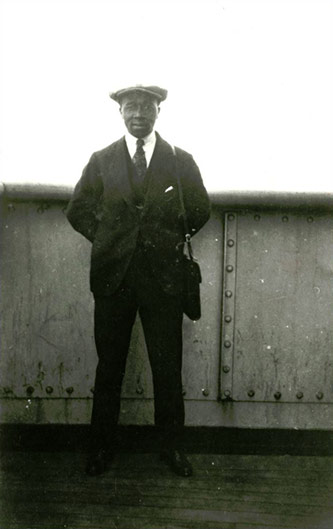

Edmund Thornton Jenkins, Courtesy of Charleston Jazz Initiative, Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, College of Charleston, Charleston, SC.

In the early twentieth century, there was a vigorous debate about what role, if any, black folk music would play in defining U.S. concert music. This question galvanized leaders and artists of the New Negro Renaissance, especially around the issue of jazz.1 To optimize political change, many black intellectuals and artists wanted to emphasize jazz’s positive association with folk authenticity, so-called primitive vigor, and black originality, while, at the same time shedding minstrel stereotypes. W.E.B. Du Bois and Alain Locke, for example, encouraged the serious treatment of black folk music.2 If incorporated into Western European traditions of art music, the spirituals (and for Locke, even jazz and blues) had the potential to showcase the cultural achievements of black Americans. Other black intellectuals pushed against this Eurocentricism and criticized the assignment of race progress solely to elites. Langston Hughes poignantly identified this “urge within the race toward whiteness” as the great racial mountain “standing in the way of any true Negro art in America.”3 Hughes commanded black Americans to embrace jazz—what he called “the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world.”4 Even Locke argued that “the cloister-walls of the conservatory and the taboos of musical respectability” were strangling the potential of powerful black folk traditions. For these leaders and artists, locating strategies to advance the race through art was shaped by apprehension about being too black or becoming too white.5 Black artistry was steeped in respectability politics wrought with anxieties about class.

Central to the Harlem Renaissance was the development of artistic expressions that championed the black freedom movement. But, as recent scholarship demonstrates, other urban centers both within and outside of the United States also contributed to these vibrant conversations. In Escape from New York, Davarian Baldwin draws attention to black Americans who traipsed the globe, mapping topographies of racial solidarity within new cultural contexts, to contribute to a broader black international movement of racial awakening.6 The cosmopolitan career of composer and jazz clarinetist Edmund Thornton Jenkins (1894-1926) exemplified the political and artistic aspirations of the international American New Negro. Jenkins traveled through and briefly lived in Atlanta, London, Belgium, Paris, Harlem, and Baltimore.7 He wrote classical music by day and led dance orchestras by night, all while devising strategies to “uplift the race” through black music.8 Nowhere were his international New Negro politics more evident than in his unfinished operetta Afram, written in 1924 after leaving the United States for the last time, disillusioned by prejudice, to return to Paris.9 Afram’s mixture of classical vocal forms and black popular music, along with its African diasporic plot, articulate the experiences of the 1920s black American expatriate, the New Negro abroad. In its negotiation of these disparate styles, the operetta engages with black intellectual discourse about music’s ability to express the black modern subject.

Cover, Afram, 1924, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, Jenkins played clarinet in his father’s famous Jenkins Orphanage Band, a bastion of early jazz. He became proficient on the violin and in composition at the Avery Institute—the city’s first free secondary school for African Americans—and he subsequently studied composition with Kemper Harreld at HBCU Morehouse College in Atlanta. In 1914, he traveled to England to lead one of his father’s orphanage bands, The Famous Piccaninnys, at the Anglo-American Exposition. In the wake of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s success, Jenkins traded in his minstrelsy-laden job to study classical composition at the Royal Academy of Music. But he never abandoned his interests in jazz. In London, he directed the Queen’s Hall Orchestra, featuring Jack Hylton, and recorded their mixture of sweet and hot styles to mark one of the earliest examples of a racially mixed band. In 1921, he was invited to Paris to direct one of the Art Hickman orchestras. Jenkins became an important connection for other black musicians traveling through Europe, including Will Marion Cook and his Southern Syncopated Orchestra, James P. Johnson, Will Vodery, and Sydney Bechet.

While jazz offered Jenkins steady employment, he believed, like Locke and Du Bois, black classical music had important political implications. He had spurts of success in this arena. He premiered his first Folk Rhapsody, an orchestral piece embellished with spirituals and ragtime rhythms, in London in 1919 and Ostende, Belgium in 1925. He won Opportunity’s Holstein prize in 1926 for both his African War Dance and Sonata in A minor for cello. For Jenkins, these compositions, rooted in black folk music and musical representations of blackness, had the potential to edify black male listeners and mobilize them as activists. After serving as a committee member of the African Progress Union, a London-based association dedicated to the “welfare of African and Afro-peoples,” he formed his own fraternal organization. The Coterie of Friends educated its members about “people of colour” and organized social gatherings centered on black classical music. Jenkins also helped W.E.B. Du Bois arrange musical programming for the 1921 and 1923 Pan-African Congresses. As an exemplary member of the “Talented Tenth,” Jenkins believed high art could guide the race toward the promise of equality. He pursued this work relentlessly, and, in addition to composing, he tried to create an all-black orchestra and a publishing firm for black music. He struggled to find patronage for these projects during his brief life, which was cut short by complications following an appendectomy in Paris at the age of thirty-two.

At the time Jenkins began writing Afram in 1924 he had taken a break from composition the year prior to lead dancebands in Paris and London. Will Marion Cook had been playing in Paris and, after encountering Jenkins in 1923, believed he was “the best musician in the colored race” and “the very best instrumentalist in any race.”10 He asked him to return to the U.S. and conduct what would become Cook’s Negro Nuances revue. He did, but the show was off to a bad start, so Jenkins withdrew before opening night. Determined to succeed in his native country, Jenkins moved in with Will Vodery in Harlem (and later Robert Young in Baltimore) while looking for work and financial support, but several months later he returned to Europe, discouraged by the lack of opportunities for black composers and entrepreneurs in the U.S.. Gwendolyn B. Bennett, writing in Opportunity, said Jenkins came to America “filled with enthusiasm about some sort of musical plan,” but he left utterly discouraged after being reminded of “the frightful prejudice that hounds the American Negro’s every thought and action.”11 Yet, his nine-month stint in Harlem and Baltimore left an indelible impression on his music; the political possibilities of black American entertainment infused Afram.

Afram, 1921, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.">

Afram, 1921, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.">

"Final," Afram, 1921, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.

The nearly complete piano and vocal manuscript indicates a three-act work which tells the story of an unnamed African Prince and Princess Bella Twita, who are in love with each other but separated by the Atlantic ocean. The Prince has won a war for the King of Dahomey, but has traveled to the United States (for unspecified reasons) and asks the Princess to come to him: “Do not let yourself be discouraged, put off by the seas and the mountains.” While waiting, the Prince attends a cabaret performance, which concludes with an eight-number revue called “The Charleston Revue.” It serves as the scenic and sonic backdrop for the couple’s reunion in the final act. Jenkins exploits the division between high art and popular music to carve out two distinct subjects: African nobility, who use traditional operatic forms and sing in French, and black American working-class entertainers, who perform ragtime-infused Tin Pan Alley tunes and sing blues numbers in English. Though Afram begins by separating popular and classical music in the first two acts, it concludes, in the third act, with the African couple uniting then joining the performance troupe to dance to a “Foxtrot for Jazz Orchestra,” based on the rhythm of the Prince’s aria. Popular music brings the lovers together, and the operatic music assigned to African nobility is absorbed and rearticulated by black American entertainers.

Jenkins’s pan-Africanism is ensconced in the plot’s narrative. When the Prince sings about the Princess, he always mentions her country, making it hard not to hear a subtext of love for the homeland of the African diaspora: “On the African earth / ardent and so far away / My hopeful love / My arms take your waste and I am at your knees.” In Afram, the Princess is Africa: the hope of equality through solidarity of black citizens living in hostile nations across the globe. Du Bois captured this philosophy better than anyone. When Jenkins was writing the operetta, Du Bois, with whom Jenkins frequently corresponded, had just conducted his third Pan-African Congress and often wrote about the continent in The Crisis. He argued for its decolonization and raised awareness about the shared struggle of the “darker races.” He also shaped the continent into a cultural symbol for black heritage and distinctiveness: “Africa is the Spiritual Frontier of human kind,” he proclaimed.12 These sentiments are echoed in Afram’s final chorus: “Long live the African country of which the lovers have come to this American land where they found each other.” Behind Afram’s love story lies an operetta fundamentally about diasporic struggle and reverence.

Afram, 1924, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.">

Afram, 1924, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.">

"Kentucky Kate," Afram, 1924, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.

Much like the highbrow musicals of Jenkins’s colleague, Will Marion Cook, Afram depicts adoration for Africa but sometimes through a reductive cultural lens that makes problematic assumptions about what it means to be and sound African. The operetta is comprised of an assemblage of references to divergent parts of the continent’s vast region. The title “Afram” refers perhaps to a setting, maybe the Ghanian river. The subtitle describes “La Belle Twita” as “Roman Africain,” calling forth an ancient North African past. And the “Danse de Guerre” (which celebrates the King of Dahomey’s victory) is a Zulu war-song, sung by the Prince’s soldiers and replete with plodding bass lines, clamorous dynamics, and harmonic dissonance. It comes from Songs and Tales from the Dark Continent (1921) by ethnomusicologist Natalie Curtis, and it was intended to be used to ramp soldiers up before a battle. Jenkins’s cocktail of African symbols yields a less-than-favorable, if not confusing, representation of the continent’s diverse inhabitants, and his treatment of Africans as soldiers performing loud and percussive music relies heavily on the primitivist stereotypes gaining traction in the 1910s. However, this simplistic characterization of Africa is complicated by the Zulu war-song’s context, which Jenkins would have encountered in the text. Its transcriber, Madikane Čele wrote:

The white man is apt to think of the black man as a yoked and subject being. But when first encountered by the British, the Zulus were a strong and proudly militant people whose highly trained armies were the pride and glory of their kings... It cannot be forgotten how, with only the [short javelin and shield], the naked hosts kept at bay the firearms of the English.13

Afram, 1924, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.">

Afram, 1924, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.">

"The Levee Lounge Lizard," Afram, 1924, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.

The historical legacy of songs such as these was a point of racial pride for New Negroes. Within a pan-Africanist framework, depictions of black Africans with warlike fortitude—like those in Countee Cullen’s poem, “Heritage,” for example—symbolized resistance to violent formations of white supremacy.

If anything in this operetta deserves a bit more scrutiny it is Jenkins’s treatment of black American folk culture, which entertains African nobility. “The Charleston Revue” sequence is a mixture of instrumental dances, vaudeville choruses, and blues numbers performed by, according to Jenkins’s annotations, an authentic Charleston-based dance troupe and a vaudeville performer in the style of Florence Mills. The songs establish the performers’ American identities through geographical references: “The Carolina Strut” and “The Charleston Crawl” are two of the dances, and “Kentucky Kate” tells us she’s not from Caroline but there for the good weather.

Two of the blues songs depict, if not caricature, southern working-class blackness. In the “slow blues tempo” of “The Levee Lounge Lizard,” the singer, using black dialect, tells us he is “Mister Rastus / Lord of Levee fame / Ain’t nobody going to make me change my name / I’ve lived for years in this self same spot / And I’ll live another two scores ‘fore I’m prepared to drop.” The piano accompaniment imitates guitar strumming, a walking bass, and a repetitive ornamental gesture emphasizing the blues scale. Called a pejorative minstrel name, this character is content in his rural obstinacy and lackluster blues career. To compensate for his lack of fame and wealth (“I ain’t no movie star / I ain’t no desert shah), he asserts his heterosexual prowess (“But when I get behind the women folks / I shows them where they are”).

Kentucky Kate, another stock character, is a “low down strutter.” Over a walking bass, she lures the audience in with her mysterious identity: “Perhaps you’d like to know who I am?” In keeping with a blues phrase structure, her melodies are, at first, syllabic and syncopated, but each phrase ends on a sustained note, letting its confident sentiment linger. She is both itinerant and feisty, not subjected to the mores of middle-class femininity and sexuality. Her identity is her invention, she proclaims, as she plays “highbrow” and “pure” but also “poh” and angry. The stereotype of the aggressive southern working-class black woman culminates in the final verse: “Nobody bet not flurry me / Cause I ain’t go tell in no high falutin words / In my powest language / I generally gives the bird.”

Afram, 1924, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.">

Afram, 1924, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.">

"Danse de Guerre," Afram, 1924, Courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research.

In these and other numbers of the full cabaret, Jenkins relies on negative black stereotypes through classed and gendered markers, which establishes a difference between the cabaret’s performers and its wealthy audience members. In this way, the operetta highlights the division between working-class blacks and black aristocracy. This distinction was central to the ideology of racial uplift. For Du Bois, it was the responsibility of “best of this race” to “guide the mass away from the contamination and death by the worst.”14 As scholars have noted, these elite black leaders distinguished themselves from the other ninety percent for self-advancement in a white supremacist world.15 Kentucky Kate and the Levee Lounge Lizard were the mass to be led by the educated and professional minority. This racial hierarchy—riddled with class anxieties—materializes poignantly when the Princess first enters the Charleston nightclub with her black servant, Liza. At the same time, the Prince, angry he is alone, interrupts the show, calling it an “empty spectacle.”

Though Afram’s depictions of blackness refracted class inequalities of the United States, Jenkins paints African Americans in a much more multifaceted way than he does his African characters. The Prince and Princess are assigned the same, static sentiment and they repeat it, with the same melodies, over the course of multiple duets and arias. The sheer number of black American characters and diversity of their expression delineate more nuanced identities. The most dynamic character is Tom, a young black man, who welcomes and seats guests at the Charleston nightclub. In the skit, Tom abruptly stops to demand a fair wage for his labor from his white manager. He brazenly asks the manager for ten percent of the evening’s receipts. Though interrupted by the start of the revue, the dialogue provides a window into Jenkins’s commitment to black equality through representation, even for the other ninety percent.

Afram is an imprint of the diasporic experiences of an African American expatriate in Europe. To probe at competing notions of ethnicity, national identification, and race, Jenkins used the hard and fast distinction between jazz and classical music that occupied the early twentieth century. His hybridized music not only reflected his ever-shifting identity, as he traversed what Paul Gilroy dubs the Black Atlantic, but also engaged with Harlem Renaissance discourse on musical representations of blackness. Afram signals a step away from Du Bois’s and Locke’s somewhat paternalistic view of black folk music and towards Hughes’s youthful and rebellious embrace of jazz. Such a shift coincides with Jeffrey Jackson’s and Tyler Stovall’s accounts of American expats living among Parisian négritude.16 Yet, Afram challenged these Euro-American visions of the modern world with its dependence on Africa as a symbol of strength and unity, as an imaginary nation whose citizens revel in choice and mobility, pleasure and freedom.

Notes

- 1 For a brilliant discussion of this complex New Negro conversation, which undergirded my introductory paragraph, see Paul Allen Anderson, Deep River: Music and Memory in Harlem Renaissance Thought (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2001).

- 2 W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 1903 (reprint, Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications, 1994), 155-164; Alain Locke, “The Negro Spirituals,” in The New Negro, 1925 (reprint, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1992), 199-200. For an analysis of these perspectives, see Anderson, Deep River, 16 and 113.

- 3 Langston Hughes, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” Nation, 23 June 1926, 692.

- 4 Ibid., 694.

- 5 Alain Locke, “Toward a Critique of Negro Music,” in The Works of Alain Locke, Charles Molesworth, ed. (NY: Oxford University Press, 2012), 137.

- 6 Davarian L. Baldwin, “Introduction: New Negroes Forging a New World,” in Minkah Makalani and Davarian L. Baldwin, eds., Escape from New York: The New Negro Renaissance Beyond Harlem, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 1-27.

- 7 Jeffrey P. Green, Edmund Thornton Jenkins: The Life and Times of an American Black Composer, 1894-1926 (Westport, CT and London: Greenwood Press, 1982). Green’s thorough biography and his procurement of Jenkins’s archives made this research possible.

- 8 My reference to racial uplift is influenced by: Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920 (Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Press, 1993) and Kevin Gaines, Uplifting the Race: Black Leadership, Politics, and Culture in the Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

- 9 The manuscript is housed at the Center for Black Music Research, whose collection and support facilitated this research: Edmund T. Jenkins, Afram, manuscript, Box 1, Folder 1-3, Edmund Thornton Jenkins Scores and Other Material, Center for Black Music Research Library and Archives, Columbia College Chicago.

- 10 Will Marion Cook to Rev. Daniel Joseph Jenkins, 7 March 1923, Box 1, Folder 2, Edmund T. Jenkins Collection, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

- 11 Gwendolyn B. Bennett, “Edmund T. Jenkins: Musician,” Opportunity 3 (November 1925): 339.

- 12 W.E.B. Du Bois, “Little Portraits of Africa,” The Crisis 27 (April 1924): 273.

- 13 Natalie Curtis, Songs and Tales from the Dark Continent: Recorded from the Singing and the Sayings of C. Kamba Simango (Ndau Tribe, Portuguese East Africa) and Madikane Čele (Zulu Tribe, Natal, Zululand, South Africa) (NY: G. Schirmer, 1921), 63.

- 14 W.E.B. Du Bois, “The Talented Tenth,” The Negro Problem: a series of articles by representative American Negroes of today (New York: J. Pott & Company, 1903), 33.

- 15 Gaines, Uplifting the Race: Black Leadership, Politics, and Culture in the Twentieth Century (Chapell Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1997); Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994).

- 16 Jeffrey Jackson, Making Jazz French: Music and Modern Life in Interwar Paris (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003); Tyler Stovall, Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light (Boston and N.Y.: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1996).