American Music Review

Vol. XLV, No. 1, Fall 2015

By David Gutkin and Marti Newland, Columbia University

On 26 and 27 June 2015, the life and work of composer H. Lawrence Freeman gained an audience and context. Columbia University hosted a performance of Freeman’s 1914 opera Voodoo, the first production since its 1928 debut, and an interdisciplinary conference, “Restaging the Harlem Renaissance: New Views on Performing Arts in Black Manhattan.” The events took place one week after the Charleston Church Massacre, where nine members of Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church were shot and killed during prayer service by a self-proclaimed white supremacist. This act of anti-black terror—too similar to those enacted during the early twentieth century—lent the reviving and reconsideration of Freeman’s work a weighty sense of timeliness. The engagement with Freeman’s life and music that weekend offered original insight into black expressive culture during and before the Harlem Renaissance. We hope it may also have served to ignite scholarly interest in the composer and lead to more performances of his operas. This edition of the American Music Review offers context for Freeman’s contributions by featuring selected papers from the conference’s “Harlem Renaissance Opera” panel.

H. Lawrence Freeman at the piano. RBML Archive c. 1921, Courtesy of Edward Elcha.

Born in Cleveland, Harry Lawrence Freeman (1869-1954) studied piano as a child and began performing as a church organist around the age of twelve.1 He was said to have been spurred to compose after encountering Wagner’s Tannhäuser as a young man. By 1891 Freeman had moved to Denver, where he formed an all-black amateur opera company to put on his first works, the libretti of which he also wrote. The Martyr (subtitled “a sacred opera”), which Freeman would later count as his first “grand opera,” was performed in Denver and then again in Chicago during the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, although it was not part of the fair itself. Set in ancient Egypt in the early days of Judaism, the opera’s exotic subject matter, lofty, faux-antique libretto, and Romantic score would set the mold for many of the approximately twenty operas Freeman composed over the next half-century.

Indeed, the plan for his life’s work—to compose a monumental corpus of “grand operas” and “music-dramas” based on the legends and histories of what he called the “darker races of the world”— began to crystallize by the close of the nineteenth century.2 An 1898 article in The Cleveland Press labeling Freeman “the colored Wagner” reads: “Freeman’s plans are to go to Europe in about two years and after a thorough course at the big conservatories to go to Africa. He wants to meet the Zulus, the Kaffirs, the Abyssinians and other nationalities and study their legends, mythology, and native music. He believes he can construct truly grand and noble operas on these foundations.”3 Freeman never made it to Africa, nor did he study in Europe. He did, however, receive lessons in the 1890s, after returning to Cleveland, from conductor and composer Johann Heinrich Beck, and in 1903 incorporated African students at Ohio’s Wilberforce University (where he taught from 1902 to 1904) into performances of his opera An African Kraal. After leaving Wilberforce, Freeman worked as music director for a number of musical comedies and theatrical organizations including Ernest Hogan’s Rufus Rastus in New York (1906), the Pekin Stock Company in Chicago (ca. 1907), Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson’s Red Moon tour (1909-1910), and John Larkins’ Royal Sam tour (1911-1912).4 Around 1912 Freeman moved to Harlem with his wife, actress-singer-director Carlotta Freeman, where he lived and worked as a composer, private music instructor, and occasional music critic for the rest of his life.

While Freeman’s ambition to weld the European operatic tradition with African sources was evident from the very beginning of his career, according to the composer’s own telling, he initially rejected the influence of African American folk music entirely. In his unpublished study, The Negro in Music and Drama, Freeman recounts a tense exchange with famed poet Paul Laurence Dunbar on the subject of African American folk culture. Dunbar, Freeman writes, had attended the 1893 Chicago performance of The Martyr. Passing through Cleveland two years later, and staying with the Freemans, Dunbar admitted his bafflement that the composer ignored “Negro themes . . . the folk, work or camp-meeting songs of the South,” and in fact all black American music. He states “There is nothing Negroid in any of your compositions.” Freeman records his reply:

“I didn’t intend that there should be. What do I know about those things?” (I was insulted –

outraged – exasperated) “Let somebody else do it; for it is all totally foreign to me. But let me

understand you, thoroughly. You mean for me to copy and utilize, for operatic purposes, those

funny-sounding noises – groanings moanings and wailings... You expect me to say ‘Dis’ and

‘Dat’ in music, do you?... Well,” I concluded; “You suit yourself: I’ll suit myself: Do all the

‘South Before The War’ stuff you wish. None of it for me!4

1947 performance of Freeman's opera The Martyr at Carnegie Hall. H. Lawrence Freeman Papers, Series VI, Box 51.

After relating this story, however, Freeman writes that he had “long since learned to love and revere these selfsme [sic] aboroginal [sic] Negro themes and melodies more than any music within the ken of mortal man.” Indeed, not only did the “South Before The War” become a recurring setting in Freeman’s operas, he also began incorporating African American folksongs and spirituals into his compositional language and Southern black dialect—or his imagination thereof—into his otherwise high-flown libretti (a slave in the “American Music-Drama” Athalia sings: “Sojers is crossin’ de fiel’ out dere, ‘Pears lak to me deys a heedin’ heah!”). With the addition of African American subject matter and music to his expansive operatic vision, by the 1910s Freeman had constructed the conceptual basis for what he called “Negro Grand opera.” “By this,” he writes in one essay, “I mean works conceived by Negro composers, based upon typical Negro life and interpreted by Negro artists.”5

For Freeman, “Negro Grand Opera,” although conceived as distinctly American, should build on the global mytho-historic project he had already embarked upon. “We also claim the right,” Freeman writes, “to depict certain episodes of the other dark skinned races, such as the [American] Indian, Mexican, Mongolian and other oriental peoples, especially those who have made their abode in Africa from time immemorial, such as the Egyptian and the Arab.”6 Among Freeman’s operas were: Valdo (1895), a “Romantic Opera,” about a nineteenth century Mexican caballero (Freeman later named his son after the title character); The Octoroon (1904), a romance about “miscegenation” in the antebellum South based on Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s serialized novel of 1861-62; An African Kraal (1903), set in Kaffirland; The Tryst (1911) and The Prophecy (1911), both about American Indians; Athalia (1916), set in the South during the Civil War; Vendetta (1923), set in Mexico; and the Zululand “African Music Drama” tetralogy (ca. 1917-43) based on the novel Nada the Lily by H. Rider Haggard.

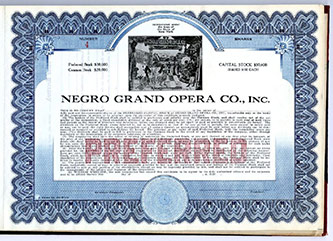

Negro Grand Opera Co. Stock. Preferred Stock $30,000; Common Stock $20,000; Capital Stock $50,000; Shares $100 each (1920). H. Lawrence Freeman Papers, Series VI, Box 51.

To produce his operas, which he continued composing even as they mostly went unperformed, Freeman began to work out plans as early as 1913 for a black opera company. Originally to be called the Colored Grand Opera Company of New York, the organization was eventually incorporated as the Negro Grand Opera Company in 1920. Seeking to sell stock in the Company at $100 a share, Freeman and his son Valdo printed flyers appealing to racial pride: “The Negro composer has not had this same opportunity for public presentation, the Caucasian not deeming it within his province to accept the Negro’s creative ability in the realms of higher art seriously . . . Hence the successful presentation of these works by a superb organization . . . who will forthwith establish irrefutable proof of the creative achievement of the great Races of the World.”7 Selling stock did not prove successful, and the Negro Grand Opera Company only managed to put on a few performances over the next decade, including Vendetta in 1923 at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem, and Voodoo in 1928 at the Palm Garden on 52nd street in the Broadway district.

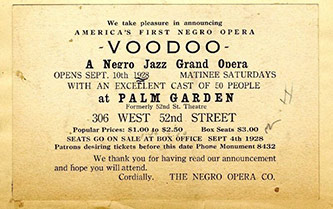

Cut short owing to poor ticket sales, the 1928 run of Voodoo at the Palm Garden nevertheless received a significant amount of attention in both New York’s white and black presses. This may have been partially owing to advertisements that designated the work with the intriguing, au courant label: “Negro Grand Jazz Opera.” In fact, Freeman had completed Voodoo in 1913 or 1914, before the word “jazz” had entered mainstream use, and in his own writings he generally referred to the work simply as “grand opera.”8 Reviews were notably mixed. The predominant criticism leveled at Voodoo in the white press when it was premiered was that it exemplified an anxiety-ridden and even perverse attachment to a rapidly receding nineteenth-century European Romanticism. One reviewer complained, “The work is supposed to be a jazz-opera, so a jazz orchestra was selected. But ‘Voodoo’ is not jazz. It is attempt to produce under the guise of negro forms the old Italian form of opera. There are arias that ape Verdi and Donizetti. There is a plot that reaks [sic] of the tragedic school.”9

The stakes and criteria for considering Freeman as modern were obviously different for Harlem society and the black press, for whom artistic innovation was almost inevitably bound up with questions of socio-economic progress and philosophies of racial uplift. Writing for the New York Amsterdam News, theater critic Obie McCollum incisively commented on a dialectic of conservatism and innovation in Freeman’s life and work. Upon stumbling into Freeman’s studio, the reviewer conceded, one might be forgiven for exclaiming: “‘Here is an old school music teacher who lives in the past.’” “Certainly,” McCollum continues, “the Elizabethan period paintings, the wall masks recalling the glory which was the Moor’s, the alabaster bust of Shakespeare, bard of Avon; the mullions and furniture in Doric, Louis IV and Ionic, and the paneled walls and ceiling in ebony, red, gold and pale green would suggest a leaning toward yesterday.” But to dwell on appearances, the author suggests, would be to entirely miss the deep strain of innovation in the work of this “pioneer composer.”10 Similar rhetoric could be found in reviews of Voodoo published in black newspapers. A headline subtitle in the Baltimore Afro-American, for example, reads “‘Voodoo,’ Race Opera Opens Up New Field—Lawrence Freeman’s Play Takes Pioneer Step in New Race Culture,” while an advance publicity blurb in the New York Amsterdam News was given the martial title, “The Negro Invades the Grand Opera Field.”11

Postcard-sized advertisement for Voodoo (1928), H. Lawrence Freeman Papers, Series VIII, Box 59.

In 1933 Freeman convinced Alfredo Salmaggi to produce and conduct Voodoo at the Hippodrome Theater, with the excellent house orchestra, provided that Freeman himself raise $2,000 for scenery and costumes. Hoping to entice Salmaggi into staging his father’s work, Valdo Freeman bombastically estimated that a production of Voodoo would “attract most of the 350,000 Negroes in greater New York.” Despite a letter-writing campaign in support of Freeman carried out in the New York Amsterdam News, the necessary funds were never raised and the Hippodrome production never took place. But the 1930s also contained some notable successes for Freeman. In 1930 he was awarded the Harmon Prize. On 25 January 1934, three one-act operas by Freeman were presented at Salem M. E. Church in Harlem to a capacity audience of 2,500 people. Later that year, Freeman’s work reached an even larger audience when he was chosen to participate in “O, Sing a New Song,” a “musical extravaganza” presented at Chicago’s Soldier Field that was “conceived to display Negro Music in an Historical way.”12

Despite a dearth of performances in his later years, Freeman seems never to have stopped imagining that his contributions to American opera would eventually achieve critical and popular acclaim. During the late 1940s he began to draw up plans for an organization to be called the Aframerican Opera Foundation, a kind of Bayreuth-in-America that would provide a platform for the performance of his works. The plan included the construction of an opera house to be built “on the outskirts of New York City, with a seating capacity of seven thousand people, and parking lot for two thousand automobiles.” Perhaps we are not quite there yet, but the conference and two sold-out performances of Voodoo at Columbia University’s Miller Theater in the summer of 2015—almost ninety years since it was last heard—is a pretty good start.

*****

Freeman, Voodoo, Act 1, Duet: "Oh Radiant Night."

Courtesy of Annie Holt and the Morningside Opera.

Freeman, Voodoo, Act 1, Mando's Aria.

Courtesy of Annie Holt and the Morningside Opera.

Freeman, Voodoo, Act 2, Chloe's Aria.

Courtesy of Annie Holt and the Morningside Opera.

Notes

- 1 The sketch of Freeman’s life and information about the reception of Voodoo that follows is drawn from David Gutkin, “American Opera, Jazz, and Historical Consciousness, 1924-1994,” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2015). This work is reliant on the H. Lawrence Freeman Papers held at Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- 2 “The Artistic Status,” (circa 1920) in H. Lawrence Freeman Papers, Series VI, Box 49, Folder 11.

- 3 “[Word missing] African Operas,” Cleveland Press, 25 March 1898. This article does not bestow the title “the colored Wagner” on

Freeman but rather observes that it is “the appellation given to Harry L. Freeman by the musicians of Cleveland.” In H. Lawrence Freeman Papers, Series VIII, Box 59. - 4 From 1908-1909 Freeman served as an organist at the Cory Methodist Episcopal Church in Cleveland. Dates and professional positions are found in H. Lawrence Freeman, The Negro in Music and Drama (unpublished typescript). In H. Lawrence Freeman Papers, Series V, Box 50, Folder 3.

- 5 H. Lawrence Freeman, The Negro in Music and Drama (unpublished typescript), 342-43. In H. Lawrence Freeman Papers, Series V,

Box 50, Folder 3. - 6 H. Lawrence Freeman, “The Negro in Grand Opera” (unidentified music trade magazine, ca. 1922). In H. Lawrence Freeman Papers,

Series VIII, Box 55. - 7 “The Negro in Grand Opera.” In H. Lawrence Freeman Papers, Series VIII, Box 55.

- 8 “The Artistic Status.” In H. Lawrence Freeman Papers, Series VI, Box 49, Folder 11.

- 9 Between 1924 and 1929 Freeman composed American Romance, a work that did in fact officially bear the subtitle “Jazz Opera.” Curiously, this was also his only opera that solely featured white, Anglo-American characters—but that is another story.

- 10 Harold Strickland, “A New Opera,” The Brooklyn Daily Times, 11 September 1928.

- 11 Obie McCollum, “The Trailblazer: H. Lawrence Freeman—Opera Composer for Four Decades,” New York Amsterdam News, 20 October 1934, 9.

- 12 “‘Voodoo’ Race Opera Closes After Short N. Y. Run: ‘Voodoo,’ Race Opera Opens Up New Field—Lawrence Freeman’s Play Takes Pioneer Step in New Race Culture—SINGING EXCELLENT—Large Chorus and Orchestra of 21 Pieces,” Baltimore Afro-American, 29 September 1928, 9. “The Negro Invades the Grand Opera Field,” New York Amsterdam News, 22 August 1928, 6.

- 13 Charles C. Dawson, “The Artist’s Conception of the Pageant,” in the official booklet National Auditions Annual, A Century of Progress, Souvenir Edition of Afro-American Pageant, Inc., Soldier Field August 25, 1934. In H. Lawrence Freeman Papers, Series VIII, Box 53, Folder 1.

- 14 The conference was organized by Annie Holt and sponsored by the Heyman Center Public Humanities Initiative, as well as the Columbia Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, The Department of Music, The Institute for Research in African American Studies and the IRAAS Alumni Council, The School of the Arts Community Outreach and Education, The Columbia Ph.D. Program in Theater, and the Rare Book and Manuscript Library. The conference planning committee members were Annie Holt, Christina Dawkins, David Gutkin, Emily Hainze, Jennifer B. Lee, Marti Newland, Matthew Sandler, Rosa Schneider, and Marcia Sells. The performances of Voodoo took place in Miller Theater through the collaboration of Morningside Opera, Harlem Opera Theater, and the Harlem Chamber Players. The opera was conducted by Gregory Hopkins and directed by Melissa Crespo. The score, used in manuscript form, was reproduced from the Columbia Rare Book and Manuscript Library, where it is included in the papers that the Freeman family donated. By appointment, the 2015 performances of Voodoo can be seen and/or heard at Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. For a full list of conference participants and their paper titles see: heymancenter.org/events/harlemrenaissance/