American Music Review

Vol. XLV, No. 1, Fall 2015

By Naomi André, University of Michigan

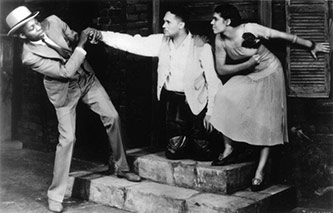

The Original Cast of Porgy and Bess. Photo by Richard Tucker, Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

To say that Porgy and Bess was produced by a racially homogenous “white” creative team does not tell the full story. Indeed, there was someone on the collaborative team who personified quintessential American whiteness: DuBose Heyward. Heyward was from Charleston, South Carolina and though his family was not as financially prominent as it once had been, he could trace his ancestors back to the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Heyward came from deep roots in a well-heeled southern white heritage. Conversely, George and Ira Gershwin were born to Russian Jewish parents who immigrated to the U.S. in the 1890s. In my discussion of immigration and the Great Migration in this opera, race matters. Though a scientific basis to biological differences rooted in race has been disproven in current scholarship, this was not the case for nineteenth-and early twentieth-century constructions of race and this directly affects Porgy and Bess. Yet rather than starting with the more expected discussion about whether or not Porgy and Bess is racially insensitive or how blackness is expressed, I will focus on how different articulations of whiteness can be found in the opera.1

Scholars in the field of whiteness studies have examined how European immigrants from the turn of the nineteenth into the twentieth centuries tried to distinguish themselves from black people when they arrived in the U.S.. Sometimes these strategies included distancing themselves from black people and trying to climb up a hierarchy where the enslaved and formerly enslaved were oppressed to the bottom of the socioeconomic and educational structure. But this was not the only tactic and sometimes immigrants joined in abolitionist and social justice movements that combined forces with African Americans and worked towards common goals of social uplift.2 Regardless of their individual stance, Jewish people experienced anti-Semitism and were branded with negative stereotypes, some of which were similar to those associated with black people.3 At the time of Porgy and Bess, this was especially relevant. Karen Brodkin, along with other scholars, cites the 1920s and 1930s as “the peak of anti-Semitism in America.”4 An area that has not received much attention in the Porgy and Bess literature is the richness of the interactions between blacks and Jews in the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s. At this time ragtime and the blues, Yiddish musicals, early jazz, and klezmer were circulating alongside each other in popular culture and their study could provide a more nuanced investigation into Gershwin’s experience and use of black musical idioms. My discussion here concentrates less on these provocative musical interactions themselves and more on their contexts; what happens when we think about constructions of race around whiteness, Jewishness, and blackness in the time Porgy and Bess was written, and how might this shape our thinking about this opera today?

The themes of travel and relocation are central to the story of George Gershwin, who came from a family that immigrated to New York City at the end of the nineteenth century. To further enrich this discussion, I want to juxtapose the concept of people moving to America with that of people moving within the United States, and specifically with the Great Migration. With this internal re-shuffling, we see a moment in American history, post-Reconstruction and after World War I, that featured the movement of African Americans from the South to the North and West. Porgy and Bess encompasses both worlds of displacement. George Gershwin’s parents, Moshe (Morris) Gershovitz and Rose Bruskin, emigrated from the area around St. Petersburg, Russia in the 1890s, and married in New York in 1895. They lived in various locations in New York’s Lower East Side—Ira Gershwin recalls the family moving twenty-eight times during his childhood, before 1916.5

DuBose Heyward. Courtesy of the South Carolina Literacy Map.

Isabel Wilkerson has written insightfully about the Great Migration in her Pulitzer Prize winning national bestseller The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration.6 In tracing the journeys and stories of hundreds of people she fleshes out the themes, places, and rhythms of the lives she documents. Wilkerson conducted her research at the turn of the new millennium, as the era she had chosen to study (1915-1970) was rapidly receding into the past and few of the original migrants remained. With their stories, this narrative of extreme poverty, utter lack of opportunities for advancement, and the ever-present threat of lynching in the Jim Crow South, is re-written into current memory and preserved in history. The caricatures of the vicious white roles in Porgy and Bess (the Coroner, the Detective, and the Policeman) feel more “real” when reading page after page of Wilkerson’s interviews, as we re-live some of the terror and constant fear of stepping out of place. The stereotypes in Porgy and Bess are usually leveled at the black characters in minstrel garb, and these are certainly present in the opera with the Jezebel Bess, Sambo Porgy, Crown the Buck, and others. Nonetheless, the exaggeration of operatic drama in the white characters serves the story well and brings to life some of the lived emotion Wilkerson captures in her documentary study of the motivations fueling the Great Migration.

Scholars have already noted a connection between some of Gershwin’s tunes in Porgy and Bess that bear resemblance to styles of Jewish klezmer and Yiddish theater as well as liturgical music. Howard Pollack’s 2007 biography of Gershwin picks out “Oh Hev’nly Father” (Act 2) as “reminiscent of a ‘davenning minyan.’”7 Geoffrey Block has demonstrated that Sportin’ Life’s “It ain’t necessarily so” is similar to the Torah blessing “Baruch atah Adonai” in melodic shape and content.8

All of the references to the Bible are from the Old Testament, indeed from the first five books of the Bible, also known as the Five Books of Moses, and the Torah (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). With cleverly crafted lyrics about David and Goliath, Moses found in the Nile by the Pharaoh’s daughter, Jonah and the whale, and Methuselah (living 900 years)—these stories work well for the Bible-believing people of Catfish Row. Moreover, they would also have resonance for those from the Jewish faith. Hence, these biblical references spoke directly to the diverse religious backgrounds of the opera’s first audiences through quotations spanning both Christian and Jewish cultural associations. Regarding the handling of “Baruch atah adonai,” the adaptation of this well known Jewish prayer appears strategically as it is featured in the “anti-sermon” (“It ain’t necessarily so”) that Sportin’ Life delivers after Sunday church services at the picnic on Kittawah Island. Making the connection between this these two religious traditions allows us today to have a greater appreciation of this charged moment, laden with religious allusions, staging multiple identities at once.

In the Great Migration from the southern U.S. to the North and West, specific urban cities emerge as prime locations for where people would settle and relocate. Chief in outlining these paths of migration were the railways that provided transportation to new homes and futures. These connections draw lines between otherwise seemingly unlikely geographical locations, with people from rural Mississippi ending up in Chicago, or people in Florida easily traveling up to New York City. Trains offered one of the main means of delivery in the Great Migration by physically transporting those formerly enslaved and their descendants to the North and metaphorically providing them with a route to a more plentiful and safer promised land out of the dangers of the Jim Crow South.9

John Bubbles, Todd Duncan, and Anne Brown in the original 1935 Porgy and Bess. Courtesy of the University of Michigan.

The conspicuous absence of this train metaphor near the end of the opera is significant. Here Sportin’ Life has a big number that lures Bess to get back on “Happy Dust,” leave Porgy (who is temporarily in jail), and join him in a high-struttin’ lifestyle in New York City. In fact, this is one of the most memorable numbers in the show: “There’s a boat dat’s leavin’ soon for New York.” I argue that the catchiness of this tune has obscured a central question: Why a boat? Who would take a boat from Catfish Row, South Carolina to New York City, especially when there were several train routes available and running between Charleston and Manhattan?10

While it is probable that Gershwin’s Porgy would take the train, the main question lurking in the background remains: why should Gershwin have him take a boat from Charleston, South Carolina to Manhattan? In fact, not even George Gershwin himself took a boat from New York City down to Folly Island (off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina) when he went there to learn more about the Gullah culture in June 1934; we know that he took the train.11 These memorable lyrics signify multiple things at once. “There’s a boat dat’s leavin’ soon for New York” presents a line of trochaic pentameter that jauntily scans with a swing beat over Gershwin’s syncopated setting. With the black dialect presented against the syncopation, we hear Porgy’s voice clearly. Yet the black man would probably find more consolation traveling in the company of other black train porters. Who takes a boat to New York City? I argue that it is Moshe Gershovitz and Rose Bruskin, Gershwin’s parents, exemplars of the Jewish emigrant experience.

I bring these things to our attention not to nit-pick with transportation routes, but to expose a broader story of how Porgy and Bess can be seen to reflect the experiences of George and Ira Gershwin. They were not only writing about the African American experience (what they knew, what they made up, what they learned while working on the show), but also an immigrant experience that was familiar in their family and to many audience members who would have attended the early productions. These were the first generation of children born to recently immigrated Russian Jewish parents who had made the migration to a “promise land” (to quote Porgy’s last number of the opera—“I’m on my way to the promise land”). And like many other Eastern European Jewish people who arrived at the end of the nineteenth century seeking opportunity, they traveled by steam ship. Does this bring a little of the Gershwin history into the opera? Were they writing themselves into history? Whatever the reason to use the word “boat” rather than “train,” the context around it deserves investigation.

In addition to being a landmark work that represents a created experience of African Americans, Porgy and Bess as an “American Folk Opera” fits into the larger history of American music, one that encompasses immigrant white and black folk cultures in the United States, as well as a troubled minstrel past. It might also tell us a little about the experiences of being Jewish—and not quite white—in the 1930s.

Notes

- 1 A sampling of the excellent literature that mentions Porgy and Bess and blackness includes: Richard Crawford “It Aint’ Necessarily Soul: Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess as a Symbol,” Anuario Interamericano de Investigacion Musical, Vol. 8 (1972): 17-38; Ray Allen “An American Folk Opera? Triangulating Folkness, Blackness, and Americaness in Gershwin and Heyward’s Porgy and Bess,” Journal of American Folklore, 117/465 (Summer 2004): 243-261; and Gwynne Kuhner Brown, “Performers in Catfish Row: Porgy and Bess as Collaboration,” in Naomi André, Karen Bryan, and Eric Saylor, eds., Blackness in Opera (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 164-186.

- 2 The literature on how immigrants to the U.S. navigated racial identities between black and white includes: Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White (New York: Routledge, 1995); Jennifer Guglielmo and Salvatore Salerno, eds., Are Italians White: How Race is Made in America (New York: Routledge, 2003); and Eric L. Goldstein, The Price of Whiteness: Jews, Race, and American Identity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006).

- 3 See Goldstein, The Price of Whiteness. A picture is reproduced from 1902 (with the caption “Is the Jew White?”) which is described as “a Jew with protruding lips and dark, kinky hair, physical traits that were often attributed to blacks in popular culture.” (45).

- 4 Karen Brodkin, How Jews Became White Folks and What that Says about Race in America (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1998), 25-26. Brodkin also cites David Gerber, ed. Anti-Semitism in American History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986) and Leonard Dinnerstein, Uneasy at Home: Anti-Semitism and the American Jewish Experience (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987).

- 5 Richard Crawford and Wayne J. Schneider, “George Gershwin.” Grove Music Online/Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed 20 June 2015, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/subscriber/article/grove/music/A2252861

- 6 Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Vintage, 2010).

- 7 Howard Pollack, George Gershwin: His Life and Work (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 46. Pollack in this connection between “Oh Hev’nly Father” and the davenning minyan cites Maurice Peress as making this observation about the similarity in the counterpoint.

- 8 Geoffrey Block, Enchanted Evenings: The Broadway Musical from Show Boat to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 77-78, Example 4.2 (b). Several Internet sites also mentioned this connection between Gershwin and this Torah blessing.

- 9 Not only a primary means of transportation, the railways were also one of the career areas for black men to earn a respectable living. For example, a specific subgroup of porters that started soon after the Civil War—the Pullman Porters—were black men hired to work on sleeping cars. As workers with gainful employment and wages, they soon formed an influential voice. A. Philip Randolph organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1925, later important agents in the Civil Rights movement. See Larry Tye, Rising From the Rails: Pullman Porters And the Making of the Black Middle Class. (New York: Henry Holt, 2004); Robert L. Allen, The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters: C.L. Dellums and the Fight for Fair Treatment and Civil Rights (Boulder, C.O.: Paradigm Publishers, 2014).

- 10 The Atlantic Coast Line RR 1900-1967 included Charleston-NYC under a different name (the Wilmington & Manchester RR connected with the North Eastern RR—which brought in Charleston in 1857). [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlantic_Coast_Line_Railroad]

- 1 “On June 16, 1934, George Gershwin boarded a train in Manhattan bound for Charleston, South Carolina. From there he traveled by car and ferry to Folly Island, where he would spend most of his summer in a small frame cottage.” David Zak, Smithsonian.com 8 August 2010. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/summertime-for-george-gershwin-2170485/?no-ist Gershwin’s train trip to Charleston is also mentioned in Robert Wyatt and John Andrew Johnson, eds., The George Gershwin Reader (New York.: Oxford University Press, 2004), 184.