American Music Review

Vol. XLIV, No. 2, Spring 2015

By Joanna Smolko, University of Georgia

From the Singers Glen Music & Heritage Festival, 2007. Joseph Funk explains shaped notes in his singing school. Photo courtesy of Gayle Davis.

As a composer, conductor, teacher, and singer, Alice Parker (1925-) has promoted and arranged American folk and vernacular materials throughout her long career, with particular attention to traditions of sacred music. In her opera Singers Glen, she recreates the musical life of a nineteenth-century Mennonite community in Singers Glen, Virginia (a small town within the Shenandoah Valley) using shape-note hymns as the foundation of the opera. The opera centers around Joseph Funk (1778-1862)—composer and compiler of multiple hymnals during the nineteenth century, including A Collection of Genuine Church Music (1832) and several editions of The Harmonia Sacra. The hymns function as historical artifacts within the opera, woven together with other historical documents, such as personal letters, to tell the story of Funk’s life and role in the community. In addition to acting as sonic history, the music and text of the hymns unfold the central conflicts of the drama—song versus dance, voice versus instrument, sacred versus secular, young versus old, progress versus tradition, assimilation versus preservation. The reenactment of two singing schools, one reflecting traditional music practices and the other with a progressive approach, unfold these core tensions of the opera.

As an educator and a composer, Parker consistently emphasizes the importance of preserving musical traditions. Much of her work consists of arrangements of preexisting songs, and she has frequently adapted shape-note hymns and incorporated them into large-scale works such as Singers Glen and her cantata Melodious Accord (1974). These arrangements give her the opportunity to interact with the past, yet she is conscious of the limits of historical reenactment, writing, “If I have a chance to arrange tunes from a certain time and place I learn about them from working with them–but my impulse is never to create a ‘historical setting’. The tune ends up being filtered through my 20th/21st-century musical ideas.”1

Parker values the ways in which these hymnals record community traditions of music. She writes, “Love songs, ballads, fast and slow dances all found their way into the shape-note hymnals, and were a vital part of the musical life in rural communities.”2 These diverse traditions are highlighted in Singers Glen, and through the narrative, the characters themselves rediscover the roots of their music. In this opera Parker uses the dramatic possibilities inherent in the genre to imaginatively recreate the community life of the town.

Singers Glen is constructed around twenty-five hymns taken from the first three editions of Joseph Funk’s hymnal A Compilation of Genuine Church Music.3 Some of these, such as “Sweet Affliction,” “Resignation,” and “Idumea” are commonly found in other nineteenth-century shape-note hymnals. Hymns such as “Lime house,” “St. Olaves,” and “Confidence” have their first known source within Funk’s editions of Harmonia Sacra. The hymns alternate with and sometimes accompany aria- and recitative-like sections, as well as sections of spoken dialogue. They also function as leitmotivs, representing particular characters as well as creating links between themes within the story line.

The narrative of Singers Glen focuses on simple moments of life, more in line with the ideals of verismo than operatic melodrama. Household chores, routine conversations, (on the weather or the price of hymnals, for example), community events, and strong yet understated emotions create the drama in the work. Even Parker’s stage directions place an emphasis on the ordinary. For example, her instruction for the set-up of the first singing school calls for young people in lively conversation, sedate elderly, rowdy children, and “a baby or two.”4

Parker conveys this community as being in a state of flux, pulled both towards the past and the future. In the discussion of the genesis of the work, Parker writes, “Fact and fiction are mingled to illustrate the basic conflict of the work, that between the artist as visionary, and the restraints of the traditional church.”5 The conflict is especially evident in the contrast between the use of instruments by Joseph and his family and the dominant view of the Mennonite church at the time—that instrumental music should not be used in worship, and further, that musical instruments reflect a worldliness that should not be present within the religious community.6

In Singers Glen, there is no simple either/or answer to the tensions between the preservation and transformation. Instead, Parker portrays almost a dialectical relationship between the two. Both the community (the Mennonite Church) and the creative individual (Joseph Funk) are portrayed as necessary parts of a whole: without growth, the community and its music would wither; without roots, the new would have no meaning. Alice Parker writes that one of the purposes of this work is to explore the fact that “Joseph’s path led in one direction—ecumenicism, a preoccupation with the art which unites people, rather than the words which divide them; and the Church’s led in another—the wish to preserve the way of life which was and is of such value.”7 The prologue of the opera sets up the dynamics that are explored more fully in the two singing schools.

The prologue opens with the funeral of Joseph Funk’s wife, in 1833, the year after the first publication of A Collection of Genuine Church Music. The first hymn “Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt” is sung in its original German.8 This sets up one of the central tensions specifically within this community of whether to preserve the German language within worship, or to assimilate to English. Singers Glen was one of the first Mennonite communities to adopt English language worship services in the United States, and this was in a great part spearheaded by the work of Joseph Funk. This prologue also introduces “Brother Peter,” a respected elder who advocates preserving the old ways. Brother Peter represents a community commitment to tradition, a foil for the creativity and innovation of Joseph Funk. Joseph is shown as a mediator of progress and change, especially through the publication of hymnals and the use of musical instruments in his family. His son Timothy likewise values progress and innovation.

As Act 1, Scene 2 begins, the hymn “Invocation” is played by the orchestra as the community readies itself for the singing school. Snippets of everyday conversation—weather, politics, bookselling, even dialogue in German—sound over a series of hymns played by the off-stage orchestra. Again, this scene emphasizes everyday life, the commonplace realities too frequently ignored in veins of historical narrative prior to the new social history. Joseph calls the singing school together by inviting the community to sing “Invocation.” After the hymn, Joseph instructs the newcomers in the art of singing using solfege and shape-notes. Parker instructs that a large chart be used to show the symbols.9 While Joseph teaches the community a detailed singing school lesson within the narrative, Alice Parker teaches the audience and the performers by proxy. This direct involvement of the audience in the tradition, history and music of the community situates the opera firmly in the context of other public history presentations. As visitors become participants in public displays of history when they meander through reenactments at places like Colonial Williamsburg, so the audience—even though they do not actually sing—become participants in this opera.

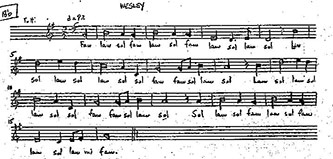

Following Joseph’s lesson, “Wesley” is sung on solfège syllables, in unison, notated in the score with the original shape-notes.10 Again, Parker creates a teaching moment: even though the audience never sees the score, the use of shape-notes in the performance score informs the performers as they learn the parts (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Parker, Singers Glen, Act 1, Scene 3, Wesley. Used by permission of Hinshaw Music, Inc.

All singers are taught the melody before the harmony and text are added. This embodies Alice Parker’s melody-centered approach to composition and music education: all parts should be taught the melody in order for all the participants to understand its structure and its relationship to other voices. Joseph then teaches the minor mode, using the hymn “Hiding Place.” The hymn begins with unison voices, but quickly transforms, using fugal textures as well as paired imitation between voices. It evokes the fuging tunes found in many shape-note hymnals (including Joseph Funk’s publications), but the imitation is freer. Again, Parker develops these hymns, exploring their melodic, harmonic and polyphonic possibilities, rather than treating them as objects to be preserved intact.

After Joseph teaches a round, Brother Peter suggests singing one of the old hymns. One of the elders chooses “Idumea,” its heavy text and minor mode creating a reflective mood. The group sings it first on syllables (emphasizing the traditional mode of performance), again with shape-notes presented in the score. The first verse is sung with slight modifications of the original harmony, followed by an imitative development of the melody in the next verse. The men and women double the treble and tenor, reflecting the performance practices of the hymns, and creating a dense, interwoven texture.

The singing continues with “Social Band,” followed by “Christian Farewell” suggested for the closing hymn. As the group sings “Christian Farewell,” most of the people exit, leaving only a handful behind. At this point, Timothy Funk’s fiancée Susan proposes that they sing another song. Hannah Funk’s fiancé Jacob asks Timothy to play the flute, but Timothy declines. This moment foreshadows the incorporation of instruments into the second singing school, a crucial moment in the narrative of the opera. For the moment, however, the traditional mode of performance wins out over more innovative additions.

Timothy instead suggests that Susan and he sing a duet for them, “Transport,” a hymn, as Parker notes in the score, transformed into a love song. Again, Parker evokes the secular/sacred tension present in the history of the hymns. The text is florid, expressive, and full of vivid metaphors, opening with, “One spark, O God, of heavenly fire awakes my soul with warm desire to reach the realms above.” She transforms this hymn into an operatic love duet through its scoring—a duet between the affianced couple, accompanied by the soaring off-stage orchestra. In this arrangement, Parker successfully re-creates two levels of history: the previous existence of many tunes like this as secular music, and the presence of the hymn as a sacred work in the community of Singers Glen during Funk’s lifetime.

Following the duet, a reprise of “Christian Farewell” concludes the singing school. Though this is the more traditional singing school, deep tensions have been introduced: new songs versus old songs, a suggestion to use a musical instrument, and a hymn transformed into a love duet. Parker probes deeper into these tensions in the second scene of the final act.

Figure 2. Parker, Singers Glen, Act 2, Scene 2, Mount Ephraim, mm. 1-3. Used by permission of Hinshaw Music, Inc.

In Act 2, Scene 2, Parker brings the sense of living history to a new level, as we see progress and creativity come into increasing tension with tradition, heightening the sense of history and hymnody as dynamic processes. In this scene, she focuses on moments in which the performance of hymns symbolizes and enacts the transformation of a tradition through the actions of a creative individual. The school is led this time not by Joseph, but by his son Timothy, and includes the young people of the community, several of whom bring their instruments. Parker calls for the string quartet that has previously performed off-stage to join the school onstage, and allows for a variety of other instruments, according to the performers’ abilities.11 In this scene, Alice Parker showcases vigorous tunes, especially emphasizing the dance-like qualities of the hymns.

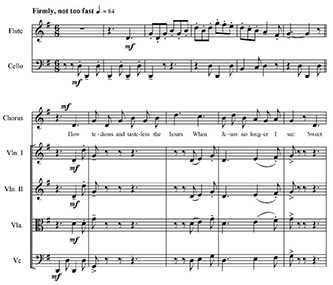

With Timothy encouraging the instrumentalists to begin, the young people begin to sing “Mt. Ephraim.” The text of the hymn itself joins in the argument for the use of instruments, as well as underscoring the nervousness of the musicians, beginning with the lines “Your harps, ye trembling saints, Down from the willows take” (Figure 2).

The instrumentalists hesitantly (perhaps even guiltily?) follow the voices before joining together with them. They quietly echo the melody just sung (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Parker, Singers Glen, Act 2, Scene 2, Mount Ephraim, mm. 4-7. Used by permission of Hinshaw Music, Inc.

After echoing the vocal line a couple of times, the instruments join with the voices. For the most part the instruments simply reinforce the vocal lines, or intertwine with them polyphonically. However, as the scene progresses, the instrumental music becomes increasingly independent from the vocal lines.

The tension in the act increases with the next hymn, “Greenwood,” during which the children start moving to the music. Not only is it a singing and playing school, it now begins to transform itself into a barn dance as well. Hannah chides the children for their levity. Someone calls for a cheerful hymn, and as “Greenfields” begins, more and more people begin dancing. Alice Parker highlights the dance qualities of this hymn through accents on the strong beats and light staccato notes on the weak beats in the instrumental parts (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Parker, Singers Glen, Act 2, Scene 2, Greenfields, mm. 1-11. Used by permission of Hinshaw Music, Inc.

The hymn’s “secular” sound is commented on in the following discussion:

Girl: I visited my cousins in Ohio. They sang like this—but game songs. And they called it a play-party.

Solomon: We can’t do game songs. Just hymns.

Girl: I don’t see the difference, if we’re moving about.

Hannah (virtuously): I call it dancing, and it comes from the devil.

Timothy: Oh, Hannah—if we’re singing God’s words, and praising him with instruments, it can’t come from the devil. Let’s sing “Christian Hope.”12

Figure 5. Parker, Singers Glen, Act 2, Scene 2, Christian Hope, mm. 1-6. Used by permission of Hinshaw Music, Inc.

As noted earlier Timothy’s view of the music reflects Parker’s own. For Alice Parker, the use of a secular tune as the basis of a hymn is in no way sacrilegious or even contrary to the text. She writes, “A folk dance with a hymn text must still dance, and a love song speak with passion. The words to a hymn are no more an end to themselves than the pitches and rhythms: both seek to define the Indefinable, know the Unknowable, and celebrate the central mystery of life.”13

In her arrangement of “Christian Hope,” Parker fully realizes the transformation from sacred back to secular music. Its lively tempo and 6/8 meter attest to its roots in Anglo-American dance music, specifically its qualities as a jig. The rhythm patterns of the strings in the opening measures (mm. 1-5) emphasize the bouncy quality of the meter (Figure 5).

The sacred-secular connection reaches its pinnacle in this scene as the folk tune “Irish Washerwoman” (noted in the score as not being found in the hymnal) is interpolated into “Christian Hope.” During this interpolation, Parker instructs that “the dance takes shape.” The visual dance reflects a crucial moment in the opera: the sacred and the secular have clearly merged (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Parker, Singers Glen, Act 2, Scene 2, Irish Washerwoman, mm. 41-49. Used by permission of Hinshaw Music, Inc.

Sacred song becomes dance, vocal music becomes instrumental music. Sharing the same meter and some of the same rhythmic patterns, the similarity between the tunes is remarkable. Through this transformation, Parker makes the roots of the hymn transparent. Again, Parker plays with layers of history: the earlier presence of many shape-note hymns as jigs and secular folksongs, and their presence in this community as sacred songs.

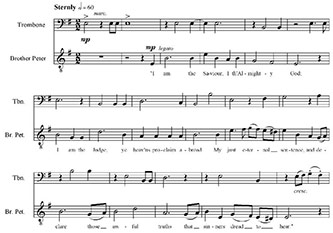

The jig continues, until interrupted by Brother Peter and the Old Couple. The music comes to a “ragged halt” as the musicians become aware of Brother Peter’s presence. Timothy goes to bring his father Joseph from the house, who is strongly reprimanded by Brother Peter for “following the world’s pattern.” He then introduces “Mount Carmel,” its text, slow tempo and E-minor tonality reinforcing the text’s caution of judgment. Its opening verse encapsulates this message (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Parker, Singers Glen, Act 2, Scene 2, Mount Carmel, mm. 1-18. Used by permission of Hinshaw Music, Inc.

Joseph responds saying, “Your text is a strong one Brother Peter. I can answer you best with another hymn, from the New Testament.” The following hymn, “Waverly,” strongly contrasts with the previous hymn, instead focusing on peace and brotherly love. Note the contrast between its opening verse and that of the previous hymn:

And is the gospel peace and love!

Such let our conversation be;

The serpent blended with the dove,

Wisdom and sweet humility.14

In the final conversation of the opera, Joseph states his philosophy, that for him, music is in no way contrary to his beliefs, “My Church, or my Music? Surely the Lord of Love, who gave us the gift of song, cannot require that I cease to sing!” But rather than setting out a new course through a complete break with tradition and his community, he tells his son Timothy, “We must learn to live at peace with our neighbors and friends. Let us pray for guidance in the days to come.” The opera concludes with the community joining in the hymn “Divine Goodness.” Peace and reconciliation prevail, even in the midst of very real conflict and tensions.

In Singers Glen Alice Parker reenacts an American musical tradition. History is not treated as a static point, but as a dynamic process even within this short period of time in a small town. Change is present, yet it takes place within an established tradition. The tensions are explored within the vastly different singing schools, but there is no simplistic resolution to the seemingly contradictory pull between tradition and progress. Brother Peter and Joseph Funk represent the two ends of the spectrum, and both are treated thoughtfully throughout the opera. Though Brother Peter is stern, he is well-respected and loved by the community. Though Joseph is innovative, he respects the members of his town. The key to bridging these binaries—as presented in the opera and within Parker’s musical philosophy—is through working within communities. She writes, “The twentieth century seems to have brought vast separations. As scientific knowledge advances, and the world shrinks, we know less and less about relating to our neighbors and preserving communal activities.”15 making reforges the connections that have been lost.

Parker complicates the issue of a sacred-secular dichotomization of music through exploring the hymns’ histories. In the first singing school, a hymn is treated as and demonstrated to be a love song. In the second singing school, a hymn historically sung a cappella has words that extol the use of instruments in worship, and a hymn is treated as a jig. The ambiguities and contradictions abound, and Parker revels in these moments. To understand these tensions, Parker argues that one must pay attention to the history and style of both tunes and text, as well as their relationship to each other. She suggests several questions that can be used to probe the relationship of the “voice” of the music with the “voice” of the text: “Do these two voices reinforce or contrast? Is attention paid to the matching of accents and loaded syllables?” What is created, she continues, when an old tune is paired with a new text or “a prayerful text” is set to “a jigging tune?”16 Only through knowing the history of these hymns can the dialectical pulls between the sacred and secular, between preservation and change, be understood.

The 1970s were years of extreme tension within American culture, a time of critique and celebration, patriotism and protest. Alice Parker does not provide an answer to the problems in America at the time, either explicitly or implicitly in this opera. However, she does give an example of a process in which change and progress come about peacefully, on the whole, without destroying the people involved or the musical tradition. Preservation and progress are oppositional forces clearly at work in the opera and in the events on which the opera was based, but Singers Glen ends with a call for changes to be initiated with both respect for the past and love for the community.

Significantly, since its premiere, Singers Glen has been performed as part of ongoing community celebrations in the city of Singers Glen. The Music and Heritage Festival of Singers Glen, taking place approximately every five years, still incorporates the opera as a crowning point in its festival. Recent festivals included performances of Singers Glen on 15-16 September, 2007,17 and on 22-23 September, 2012.18 Thus the opera has been incorporated into the very traditions that it celebrates, demonstrating that through respect for tradition and community, the “vast separations” of the twentieth-century can indeed be bridged.19

Notes

- 1 Alice Parker, interview by author, e-mail, 26 April 2006.

- 2 Alice Parker, Creative Hymn-Singing: A Collection of Hymn Tunes and Texts with Notes on Their Origin, Idiom, and Performance, and Suggestions for Their Use in the Service, 2nd ed. (Chapel Hill, NC: Hinshaw Music, 1976), 48.

- 3 Parker conducted much of her research at the Historical Library at Eastern Mennonite College, Harrisonburg, VA (interview with author). Except where noted, all hymns are from the first three editions of A Compilation of Genuine Church Music (1832, 1835, 1842).

- 4 Alice Parker, Singers Glen: An Opera in a Prologue and Two Acts, piano and vocal score (Chapel Hill, NC: Hinshaw Music, 1978), 60.

- 5 Unpublished program notes quoted in John Yarrington, “A Performance Analysis of ‘Martyrs’ Mirror,’ ‘Family Reunion’ and ‘Singers Glen,’ Three Operas by Alice Parker” (DMA diss., University of Oklahoma, 1985), 121-122.

- 6 Even to this day, some of the most conservative Mennonite denominations and communities discourage or forbid the use of musical instruments—in worship or the home—because of their “worldly” qualities. See Cornelius Krahn and Orlando Schmidt, “Musical Instruments,” in Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/M876ME.html/ (accessed 10 March 2008).

- 7a Unpublished program notes, quoted in Yarrington, “A Performance Analysis,” 121-122.

- 8 It is taken from Joseph Funk’s earliest and only German-language hymnal, Ein Allgemein nützliche Choral-Music (Harrisonburg, VA.: Gedruckt bei Lorentz Wartmann, 1816).

- 9 Parker, Singers Glen, piano and vocal score, 60.

- 10 Ibid., 72.

- 11 Parker, Singers Glen, piano and vocal score, 124. She directs, “Other casual instruments are brought by chorus members who play when they wish: recorders, dulcimers, zithers—all very informal.”

- 12 Ibid., 100.

- 13 Parker, Creative Hymn-Singing, 48.

- 14 Parker, Singers Glen, piano and vocal score, 176.

- 15 Alice Parker, Melodious Accord: Good Singing in Church (Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 1991), 14.

- 16 Parker, Melodious Accord, 23.

- 17 See http://gleneco.blogspot.com/2007/09/music-like-sublime-scriptural-poetry-is.html (accessed 16 August 2013).

- 18 See http://www.donovanumc.org/MusicandHeritageFestival2012 (accessed 16 August 2013).

- 19 Parker, Melodious Accord, 14.