American Music Review

Vol. XLIV, No. 2, Spring 2015

By Will Fulton, LaGuardia Community College and the CUNY Graduate Center

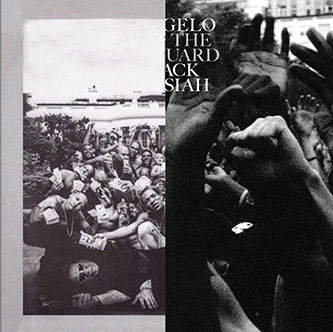

Juxtaposed album cover images of Kendrick Lamar, To Pimp a Butterfly and D’Angelo and the Vanguard, Black Messiah

When asked in a 2012 interview how he would classify his sound, D’Angelo responded: “I make black music.”1 While this may seem a flippant remark about genre categorization, this statement reveals the crux of D’Angelo’s creative process: the conscious synthesis, celebration, and continuation of African American musical traditions. Although D’Angelo (b. Michael Archer 1974) and Kendrick Lamar (b. 1987) differ artistically, Lamar’s album To Pimp a Butterfly (Interscope, 2015) demonstrates a similar compounding of black music genres, reclaiming and reconciling styles and eras toward evoking a historically unified African American music.

Both D’Angelo’s and Lamar’s recent albums are challenges to the respective genre taxonomies of soul and rap. To Pimp a Butterfly co-producer Terrace Martin comments: “I don’t know what to call this album. Some people call it jazz … but it’s heavily black in general!”2 As in the recent work of Prince, Erkyah Badu, and Kanye West, D’Angelo and Lamar index African American musical styles of the past in a dynamic relationship of nostalgic revivalism and vanguardism. On Black Messiah (Sony Music, 2014), D’Angelo and his band The Vanguard weave a self-reflexive musical tapestry that juxtaposes hip hop, boogie woogie, R&B balladry, Afropunk, and gospel quartet singing into a fluid continuum: black music. In a different context, but with a like historical focus, Lamar and his To Pimp a Butterfly collaborators merge diverse genres within a conceptual narrative that addresses racial politics and black celebrity, musically reconciling fissures between styles and generations of African American music.

Few albums in recent years have garnered such fervent critical interest as Black Messiah and To Pimp a Butterfly. However, while many commentators have focused on these albums for their originality within the marketplace, and often on D’Angelo and Lamar as creative auteurs, the performers’ relationships to larger networks of musicians, and the historiographic interests evident in these works demand further inquiry. This article will address how these performers exemplify the recent, politically charged wave of cultural historicism in African American popular music.

The ability of recording technology to preserve the vibrant history of African American music has long been recognized. In 1963, poet Langston Hughes considered the value of sound recordings in preserving musical voices for future generations, awed that “[p]osterity, a 100 years hence, can listen to Lena Horne, Ralph Bunche, Harry Belafonte, and Chubby Checker.”3 Given the central influence of black cultural production on the history of American popular music, beginning with minstrelsy, and the importance of orality and timbre in performance of African American music, the potential of sound recording to preserve the humanity and subjectivity of the performing voice is particularly significant. As Alexander G. Weheliye states, “[s]ound recording and reproduction technologies have afforded black cultural producers and consumers different means of staging time, space, and community in relation to their shifting subjectivity in the modern world.”4

As self-reflexive, conscious musical statements about the present informed by the “spirit” of past performers, Black Messiah and To Pimp a Butterfly provide D’Angelo, Lamar, and their collaborators strategies to stage current black musical culture within a continuum of African American cultural production and experience. The historical present offered on these recordings celebrates vibrant but often overlooked musical networks of African American church band, jazz, and rock musicians—communities of working musicians that are often invisible in mainstream pop culture. While for Lamar, this indexing of black music history is connected to the conceptual narrative of To Pimp a Butterfly, for D’Angelo it has been an evident— if not central—aspect of his creative process since his debut album Brown Sugar (EMI, 1995).

When entertainment manager Kedar Massenburg was seeking a marketing term for the music of his artists D’Angelo and Erykah Badu in 1997, he chose “neo-soul”: music that carried the spirit of 1960s and 1970s soul but reimagined for the hip-hop generation. D’Angelo came to reject the term, because he felt the genre distinction was too restrictive, preferring the wider, more inclusive categorization of “black music.”5 Although I had not heard the label when I first saw D’Angelo perform live, at the Supper Club in New York City in August 1995, the reasoning behind “neo-soul” seemed appropriate, if restrictive. Leading a large band complete with a brass section and backing vocalists, D’Angelo held court, seated at the Fender Rhodes electric piano, seamlessly incorporating covers of Al Green’s “I’m So Glad You’re Mine” (Hi, 1972), Smokey Robinson’s “Cruisin’” (Tamla, 1979), and quotations of the Ohio Players and Mandrill into his own hip-hop influenced sound.

For D’Angelo, affectionately termed a “scholar” by Vanguard singer and Black Messiah collaborator Kendra Foster,6 how performers carry on traditions in African American music is important. D’Angelo states of R&B singing:

After the Gap Band, Aaron Hall represented someone who was carrying on that tradition from Charlie Wilson. As far as that style of funk singer goes, we call them “squallers.” All of them were emulating Sly Stone … Who was emulating Ray Charles, of course … [Stevie Wonder] brought these vocal mechanics into the squall that other motherfuckers just couldn’t do. The only other motherfucker after Stevie Wonder, to me, that did it like that, was Charlie Wilson from The Gap Band. Aaron Hall represented the next generation of that. He was the next Charlie Wilson.7

D’Angelo’s perception of a clear historical trajectory – spanning from the 1950s and 1960s (recorded) performances of Ray Charles to Aaron Hall’s vocal technique in the late 1980s and early 1990s – is significant, and he consistently judges his own musical output against this continuum of black musical performance. Unlike his R&B influences, however, D’Angelo started his recording career as a rapper, in the Virginia-based group I.D.U. Productions. A product of the hip-hop generation, D’Angelo made music that merged the sensibilities of hip hop (such as thick “boom-bap” kick and snare patterns of the drum machine) with the earthy vibrations of musicians from an earlier era whose music was often sampled by hip hop. Like many musicians of his generation, D’Angelo learned about the breadth of black musical genres from an older relative who had a record collection, an uncle who was a DJ and introduced him to “jazz, soul, rock, and gospel history, from Mahalia Jackson to Band of Gypsys, from the Meters to Miles Davis to Donald Byrd,” a process that D’Angelo describes as “going to school.”8

D’Angelo recalls perceived similarities in the 1980s drum machine programming style of pioneering hip-hop producer Marley Marl to the late 1960s playing of Band of Gypsys drummer Buddy Miles.

[W]e went over to [I.D.U. deejay] Baby Fro’s house, he would always have some new record up, looking for breaks [to sample]. That’s the first time I heard Band of Gypsys. When I heard it, I thought I was listening to something new. Buddy Miles’ pocket sounded like Marley Marl to me… It was an “Ah ha!” moment for me because all of this music was made way back in the ’60s. It felt so fresh… It was a real revelation for me.9

Here he recounts the “revelation” in the similar thinking behind Miles’s 1969 rhythmic “pocket” and Marley Marl’s 1980s programming: a perceived connection between the rhythmic aesthetics of generations of black musicians working in different genres. While this relationship with records is far from unique, D’Angelo’s infatuation with infusing layers of historical influence into his work would become an important aspect of his creative focus, if not a career obsession. He has described dreams of talking to the late Marvin Gaye, and how the spirit of Jimi Hendrix at Electric Lady (the studio Hendrix built in the late 1960s, where D’Angelo recorded Voodoo in the late 1990s) was a major influence in his adding guitar to his music.

D’Angelo’s second album, Voodoo (Virgin, 2000), is further evidence that historical connection of black music genres was an important facet of D’Angelo’s process. On the single “Devil’s Pie,” D’Angelo imagines a slavery-era field holler set to a hip-hop backing track produced by DJ Premier. He states of “Devil’s Pie,” “I would say the spirit of the vocals was more like a chain gang, or like the feel of the slaves, the field slaves in the field picking whatever the fuck master had us picking, and that’s what we’d be singing.”10 Voodoo was lauded by critics and fellow musicians alike, with Beyoncé recently describing it as the “DNA of black music.”11

Left to right: Jesse Johnson (guitar), Cleo “Pookie” Sample (keyboards), and Kendra Foster (vocals) performing at the Best Buy Theatre, 11 March 2015. Photo by author.

Following Voodoo, D’Angelo had an extended absence from public performance. While the dramatic story of his personal struggles during this decade-long period has been well documented, D’Angelo’s musical journey during these years and how it impacted the creative process for Black Messiah is less discussed. Whereas he had worked in a social collective to create Voodoo, he began a follow-up album soon after on which he considered performing every musical and vocal part. As co-manager Alan Leeds recalls, his goal “was to record like Prince: complete creative control.”12 While products of this isolated period of recording formed some of the early versions of Black Messiah tracks, D’Angelo began incorporating other musicians and collaborators in his process, many of whom had connections to black music’s past and present. These included Jesse Johnson, former guitarist of The Time (and performer in Purple Rain), rapper Q-Tip of A Tribe Called Quest (as album lyricist), Leeds, a former road manager for James Brown and Prince, and singer/songwriter Kendra Foster, who at the time was touring as a backing vocalist with George Clinton and the P-Funk All-Stars.

Early descriptions of the music being recorded for Black Messiah stressed the influence of Hendrix and Funkadelic. In a 2014 interview, D’Angelo credited the importance of “crate digging” (slang for looking through record crates for grooves and samples) in his shift toward rock:

It’s a natural progression for me [toward rock], but honestly, I just feel like that’s where it’s going. The thing with me is, about rock and all that, years and years of crate digging, listening to old music, you kind of start to connect the dots. And I was seeing the thread that was connecting everything together, which is pretty much the blues, and everything, soul or funk, starts with that. That’s kind of like the nucleus of everything, the thread that holds everything together.13

It is unclear whether “where it’s going” here should be interpreted as the creative direction of his own sound, or how he perceives a general historical flow in black music. Obviously, however, D’Angelo sought to reconcile Hendrix’s style of rock, funk, and R&B in a way that spans fissures in the reception history and marketing of black music. Hendrix’s music, notably rejected by influential R&B DJ Frankie Crocker in the late 1960s, was not played on black-centered radio programming, or widely appreciated by black audiences during his lifetime. As James Brown and Parliament-Funkadelic bassist Bootsy Collins comments, “when Jimi [Hendrix] came on the scene, black people as a whole was not ready for that!”14 While in the 1970s, Hendrix’s heavy guitar style provided an indelible inspiration to a wide range of R&B artists, including the Temptations, the Isley Brothers, and progressive psychedelic groups like Funkadelic, it remained on the margins of R&B radio.15

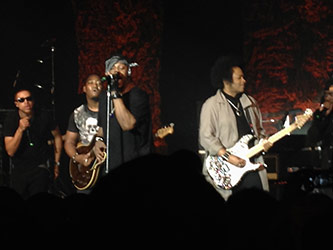

Left to right: Charlie “Red” Middleton (vocals), Isaiah Sharkey (guitar), D’Angelo, Jesse Johnson (guitar) performing at the Best Buy Theatre, 11 March 2015. Photo by author.

D’Angelo clearly considered the Black Messiah album a turn towards rock and funk, a distinct shift from his previous album Voodoo. Given his acute historical awareness, his attitude suggests a politicized reclaiming of the legacy of black rock guitarists in the face of taxonomic genre constraints put on soul/R&B and rock as respectively racially stratified “black” and “white” genres. In the album’s opening track, “Ain’t That Easy,” D’Angelo layers swelling guitar feedback that evokes the style of Hendrix and Funkadelic’s Eddie Hazel, before giving way to a push-and-pull syncopation in the introductory groove. The verse for “Ain’t That Easy” merges the quartet singing of groups like the Gospel Hummingbirds, a groove and chord progression reminiscent of Otis Redding’s “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay” (Stax/Volt, 1968), and heavy overdriven guitar timbres of Hazel and Hendrix. Meanwhile, the drum machine programming features bright, synthetic claps common in the music of Prince, as well as the loose rhythmic pocket of hip-hop.

D’Angelo’s opening Black Messiah track is an aural statement—a tapestry of genres of African American music. The layering of multiple, harmonizing, slightly heterophonic vocals with different levels of textual coherence, if in part a nod to the loose singing style of groups like the Gospel Hummingbirds, accentuates the problem of clarity. Many reviewers and fans have commented on (or complained about) the “mumble” of D’Angelo’s Black Messiah vocal performance. For D’Angelo, the less comprehensible vocal tracks represent a spiritually guided pre-verbalization, his initial “pure” vocal reaction to the recorded instrumental track.

You know, you’re putting your voice down on tape … it’s all about capturing the spirit. It’s all about capturing the vibe. I’m kinda a first take dude. The first time, cut that mic on and the spirit is there and what comes on the mic, even if I’m mumbling, I like to keep a lot of that initial thing that comes out. Cause that’s the spirit.16

The concept of being a vessel for “the Spirit” to speak, be it the Holy Spirit, or spirits of the dead, is a recurring concern for many African American musicians. As I will examine below, Kendrick Lamar also stresses the importance of the performer as vessel, and the role of the spirit in black musical production. The quest to be a spiritual conduit impacted several aspects of D’Angelo’s creative process, including the hiring of church musicians. He states:

The thing about the church is, what I learned early—they used to say this when I was going to church … “Don’t go up there for no form or fashion.” So I guess what that means is, “Listen, we’re up here singing for the lord. So don’t try to be cute,” you know. “Cause we don’t care about that. We just want to feel … what the spirit is moving through you.” And that’s the best place to learn that. So you shut yourself down and let whatever’s coming, come through you.17

D’Angelo enlisted a number of Virginia-based church musicians, including singer Lewis Lumzy. In recruiting younger, previously unknown performers from church bands to perform on tour and on Black Messiah recordings, D’Angelo brings mainstream attention to a vast well of active church musicians in communities across the U.S., widening further the scope of his celebration and continuation of African American musical traditions past and present.

D’Angelo and the Vanguard perform at the Apollo Theatre, 7 February 2015. Photo by author.

D’Angelo’s celebration of the spirit of past performers plays an important, even theatrical, role in his live performances. At the Apollo Theater performance on 7 February 2015, D’Angelo and the Vanguard incorporated a quotation of Hendrix during a performance of “One Mo’ Gin.” Transitioning from the slow, soulful groove into a heavy rock riff lead by Jesse Johnson’s guitar, the Vanguard broke into a climactic moment from Hendrix’s epic “1983 (A Merman I should Turn to Be)” (Reprise, 1968) as D’Angelo pointed upward. Although the origin of the quotation and the meaning of his gesture —pointing up to, and saluting Hendrix in heaven—may have been largely lost on the audience, D’Angelo wasn’t necessarily making the reference to play to the crowd’s interest or prior knowledge, as much to “dig in the crates” to share with them connections between African American musical genres.

This celebration and synthesis of past styles on Black Messiah is further exemplified on the track “Sugah Daddy.” The rhythm is built around a “hambone,” also called a “body pat” or “pattin’ juba” rhythm, performed by veteran R&B drummer (and septuagenarian) James Gadson. Samuel Floyd locates the origin of this term in early African American musical life:

When folk-made or makeshift instruments were not available, individuals and groups patted juba. “Patting juba” was an extension and elaboration of simple hand clapping that constituted a complete and self-contained accompaniment to dance.18

Merging the syncopation of the hambone “body pat” with the “boom bap” kick and snare pattern, and a sparse three-chord chromatic riff reminiscent of Lou Donaldson’s soul jazz recording of “It’s Your Thing” (Blue Note, 1969), D’Angelo unites hip hop, a relatively recent genre, with one of the earliest African American musical traditions. In live performance, this song takes on additional layers of historical significance, as D’Angelo extends it into a funk jam session, referencing the bandleading techniques made famous by James Brown by calling for a specific number of synchronized “hits,” and incorporating microphone stand choreography and Brown-influenced screams.

Left to right: Pino Palladino (bass), D’Angelo, Jesse Johnson (guitar), Cleo “Pookie” Sample (keyboards), and Kendra Foster performing at the Best Buy Theatre, 11 March 2015. Photo by author.

At the February 2015 Apollo performance, D’Angelo and the Vanguard strengthened the James Brown connection by transitioning from “Sugah Daddy” into a performance of Fred Wesley and the J.B.’s “You Can Have Watergate But Gimme Some Bucks and I’ll Be Straight” (People, 1973), a track that was both produced by and featured Brown.

A frequent collaborator, Questlove jokes that D’Angelo’s “sound” stems from his “utter disregard of time … be it release dates, be it prompt[ness] for shows, be it quantized meter or be it musical references; its his sound.”19 Whereas the fluidity of connection of genres and historical periods in some ways disregards time, in other ways it stages the history of black music, bringing new attention and valuation to past traditions, pioneering performers, and the networks of church musicians in African American communities.

If Black Messiah brings exposure to working church musicians, To Pimp a Butterfly celebrates a community of Los Angeles-based jazz musicians who have had a recurring role in Lamar’s music. Just as D’Angelo seamlessly juxtaposes historical influences across periods, Lamar and his collaborators were influenced by a wide range of genres and African American performers. As saxophonist and album co-producer Terrace Martin states:

We didn’t listen to the Beatles to do this record. No disrespect. We didn’t listen to the Who … We listened to Parliament. We listened to John Coltrane. We listened to Biggie … Jimi Hendrix, B.B. King, Guitar Shorty, Bobby Blue Bland, Little Walter, Little Richard—all the Littles!20

The album concept illustrates Lamar’s personal journey through African American life and celebrity in the shadow of the trials and tribulations faced by many mainstream black cultural producers. Hip-hop recordings have historically had an intertextual relationship with the past through references, via digital sampling, interpolation, and lyrical quotation. At various points, such as in the music of Public Enemy, these references have taken on increased political significance as markers of black music history and cultural production, both evoking and critiquing previous eras of African American cultural history. Evidencing the recent wave of cultural historicism in African American music, Lamar and his creative partners weave textual and musical references throughout To Pimp a Butterfly.

This is exemplified on the album’s third single, “King Kunta.” With a lyrical narrative that references Kunta Kinte, a latter-18th century slave character from Alex Haley’s 1976 novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family. “King Kunta” pays tribute to Compton rapper Mausberg, who was killed in 2000, while juxtaposing quotations of Michael Jackson, Jay-Z, and James Brown. The drum programming and bass line for the single are loosely interpolated from Mausberg’s single “Get Nekkid” (Shepherd Lane, 2000), a track produced by influential L.A.-based producer DJ Quik, while the cadence and elements of the lyrics in the first verse are derived from James Brown’s “The Payback” (Polydor, 1973).

Lamar furthers the intertextuality of “King Kunta” on the third verse, incorporating a lyric from Jay-Z’s song “Thank You” (Roc Nation, 2007) at 2:07, and the line “Annie are you O.K.?” at 2:34, from the chorus of Michael Jackson’s single “Smooth Criminal” (Sony, 1987). Connecting Brown’s 1970s bravado to the story of Kinte’s 1760s passage to America and slavery, while referencing Compton rap history, Jay-Z, and Michael Jackson, Lamar unifies generations of African American musicians and cultural history.

According to Terrace Martin, co-producer of “King Kunta,” there wasn’t a conscious discussion of incorporating different genres while making the album, but an ongoing mediation of racial politics and black cultural experience influenced the music:

Everybody on the record really understands what it’s like to be black in this day and age in America. Way before we did the music, it was important that everybody [understood] what being black was really about … It wasn’t, “We’re gonna do jazz, we’re gonna do funk,” we just wanted to be the soundtrack to [Kendrick’s] experience. What other music to do behind that but black music.21

Martin’s presence on the album is significant, as Lamar’s lyrics on several songs interweave with Martin’s contemplative alto sax improvisation, a duet-like integration of rap performance and jazz instrumentality that is rare, certainly for a mainstream, major label hip-hop release.

Martin, who has also produced beats for Snoop Dogg and Warren G., and contributed to a range of jazz projects, had previously performed with pianist Robert Glasper and bassist Thundercat (b Stephen Bruner) as 3ChordFold Live in 2014, and as the Terrace Martin Band in 2012. Martin states: “the jazz community is very small … I’ve been playing with these guys and writing music forever. They’re a very strong supporting musical cast.”22 Lamar has worked with Martin since his independent release Section 80 (Top Dawg Entertainment, 2011), which featured Martin’s band performing a live jazz instrumental backing to Lamar’s blend of spoken word poetry and rap on the Martin-produced track “Ab-Souls Outro.”

Lamar and Martin build a similar type of jazz-rap hybrid on To Pimp a Butterfly’s “For Free?,” merging the fluidity of live jazz performance with Lamar’s stream-of-conscious lyrics, recalling both slam poetry and the past performance practice of Saul Williams, Gil Scott Heron, and others. Pianist Robert Glasper describes the “For Free?” session:

I walk into this hip-hop session and I’m doing straight ahead jazz … I did like one take or two takes, but [Martin] was like, “Nah bud, dig in. Don’t worry about a thing, don’t think of it like a hip-hop thing, anything like that. Really dig in, like you’re hitting at the [Village] Vanguard or some shit … I was thinking of it like [Lamar] was a saxophone player, you know what I mean. Not like a singer or an MC, but literally like a saxophone player, it was like some jazz shit.23

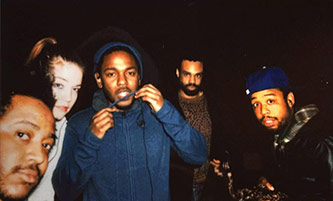

Left to right: Stephen “Thundercat” Bruner, Anna Wise, Kendrick Lamar, Bilal, Terrace Martin. Courtesy of Sonnymoon.

Incorporating the ethos of collective improvisation into hip hop, Lamar provides fresh mainstream exposure to the communities of jazz artists who have played a significant role in producing and performing hip-hop and R&B, but rarely have an opportunity for individual recognition. Lamar formed a loose collective of musicians for the studio sessions that included Martin, Thundercat, and singers Bilal and Anna Wise, all of whom worked on a number of songs on To Pimp a Butterfly over a two-year period.

This group of musicians was featured with Lamar on Stephen Colbert’s show The Colbert Report on 16 December 2014, performing an untitled song that was not recorded or released. During the performance, Lamar introduced Thundercat, Bilal, Wise, and Martin by name, bringing awareness to the networks of musical contributors to mainstream albums and live performances that are often unrecognized.

Martin, Thundercat, and Glasper all contributed to the jazz suite at the end of To Pimp a Butterfly on the track “Mortal Man,” to accompany an “interview” by Lamar of Tupac Shakur, created by interspersing soundbites drawn from an unreleased 1994 interview recording of Shakur with Lamar’s questions. The seventy-three minutes of To Pimp a Butterfly that precede Shakur’s appearance feature newly recorded contributions from Ronald Isley, Snoop Dogg, and George Clinton juxtaposed with a web of lyrical and musical allusions of past African American musicians. The first appearance of Shakur’s voice (at 6:49 of “Mortal Man”) strikingly evokes another spirit in the tapestry of black music history. The importance of the spirits speaking through musicians is exemplified by an “exchange” between Lamar and the samples of Shakur that begins at 9:59:

Lamar: In my opinion, the only hope that we kinda have left is music and vibrations. A lot of people don’t even understand how important it is, you know. Sometimes I can get behind a mic, and I don’t know what type of energy I’m gonna push out, or where it comes from …

Shakur: That’s the spirit. We’re not even really rapping, we’re just letting our dead homies tell stories for us.

Lamar: Damn …

Using the technology of digital recording, Lamar stages a conversation that merges the intertextuality of hiphop sampling with the evocation of a “speaking spirit” of Shakur in order to create a discussion that considers the importance of past voices in African American music.

Lamar’s use of live instrumentation and the celebration of black music history on To Pimp a Butterfly were initially met with some resistance from hip-hop radio and press, who expected the hard-core, minimal aesthetic of drum machine “boom-bap” patterns common in hip-hop, and much of Lamar’s earlier work. Preceding the March 2015 release of the album, the first single “i” was released in October of 2014, prominently featuring the combination of live instrumentation and a sample of the Isley Brothers’ “That Lady” (T-Neck, 1973). The song includes a replayed sample of a psychedelic, phased and distorted guitar riff that was originally performed by Ernie Isley, a nod to Hendrix’s timbre and performance style (Hendrix had served as a guitarist for the Isley Brothers for a short time in the mid-1960s). Lamar intimates knowledge of the Hendrix connection in the song’s lyric “the wind can cry now,” a likely reference to the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s single “The Wind Cries Mary” (Track, 1967).

In a November 2014 interview with Hot 97 hip-hop radio personality DJ Ebro, Lamar was questioned about the evident change in style of “i.” Ebro noted, with evident disappointment, that “this record [“i”] feels acoustic, it feels live instruments, [whereas your previous album] Good Kid, M.A.A.D City, a lot of it felt like some real sampled, 808 Production elements, using drum machines.”24 Lamar defended incorporating instruments, arguing that it would sound even “rawer” (a coveted aesthetic in hip hop): “If anything … It probably feel even more raw, because it’s a little bit more dirty with the live dirty drums on it, it’s not something that’s contemporary with the MPC [drum machine] and you’re pressing, different [drum] patterns.” When questioned about the “pop” qualities on “i,” Lamar responded tellingly about the importance of reclaiming the sound as “black” music:

I think the classifications of music is totally twisted, because now you have a generation where you take an Isley Brothers sample which is soul, and now you’re in a world where people consider it pop … I want to revamp that whole thing, and put it back to its original origins … and not be scared to say: “This is not that, this is black! Young kids gotta know this!”25

As D’Angelo reclaims rock on Black Messiah tracks and in live performances, Lamar here stresses the political importance of teaching younger African Americans about their musical heritage through connecting the diverse styles in the history of black music.

Black Messiah and To Pimp a Butterfly are albums released in an era when racial politics, both in popular music and in U.S. culture in general, have made avoidance of the discussion of race difficult. Clover Hope writes that due to recent events, “I never felt my blackness more than I have in the past three years” and that To Pimp a Butterfly “is music that makes you hyper-aware of this blackness.”26 As a white music historian who previously worked in the music business marketing black music genres, writing about these albums has made me acutely aware of ongoing tensions in the racial politics of popular music. In the shadow of a recent wave of appropriations of black cultural idioms by white performers, the identification of music as “black” rather than “hip hop” or “soul” takes on increased significance.

Historical distance will show the extent to which recent trend s will influence perception of music and its history. What is clear is that black music as a concept will continue to be relevant as long as a climate of racial politics exists. As long as white performer Miley Cyrus asks for music that “feels black,” as her producers stated in 2013, her performance of that music can never be regarded as “post-racial.”27 At a time when white singer Sam Smith is deemed “The New Face of Soul” by one critic28 while veteran rapper Scarface opines that African American rappers will one day be marginalized historically as Chuck Berry was in rock history, the celebration of black music and historical consciousness in Black Messiah and To Pimp a Butterfly is both political and timely. Prince stated at the 2015 Grammy Awards that “albums still matter.”29 The fervent interest from fans and critics in D’Angelo’s and Lamar’s albums corroborates Prince’s statement, but it also highlights the “matter” that those albums continually bring into focus: the vibrant history of black music, and the often unrecognized communities of working musicians who continue to preserve and develop musical traditions.

Notes

- 1 D’Angelo quoted in interview with Nelson George, “D’Angelo 2014 RBMA Lecture,” Red Bull Music Academy online, http://www.redbullmusicacademy.com/magazine/dangelo-lecture, accessed 15 March 2015.

- 2 Justin Charity, “Interview: Terrace Martin Talks the Traumas and Close-Knit Collaborations that Inspired Kendrick Lamar’s New Album,” Complex online, http://www.complex.com/music/2015/03/interview-terrace-martin-producer-to-pimp-a-butterfly, accessed 15 March 2015.

- 3 Langston Hughes, “Long Gone, Still Hear Voices,” quoted in Suzanne E. Smith, Dancing in the Street: Motown and the Cultural Politics of Detroit (Cambridge: Harvard , 1999), 92.

- 4 Alexander G. Weheliye, Phonographies: Grooves in Sonic Afro-Modernity (Durham: Duke, 2005), 20.

- 5 D’Angelo, quoted in George interview.

- 6 Kendra Foster, Facebook post, 11 February 2015.

- 7 D’Angelo quoted in Chairman Mao, “Interview: D’Angelo on the Inspirations Behind Black Messiah,” Red Bull Music Academy online, http://www.redbullmusicacademy.com/magazine/dangelo-black-messiah-inspirations-interview, accessed 1 April 2015.

- 8 Amy Wallace, “Amen! (D’Angelo’s Back)” GQ online, June 2012. http://www.gq.com/entertainment/music/201206/dangelo-gq-june-2012-interview?currentPage=1, accessed 15 March 2015.

- 9 Chairman Mao interview.

- 10a D’Angelo, quoted in George interview.

- 11 Saint Heron, “Solange, Janelle Monae, Thundercat, Beyoncé and More Celebrate 15 Years of D’Angelo’s ‘Voodoo’ album,” Saint Heron online, 4 February 2015, http://saintheron.com/featured/saint-heron-and-friends-celebrate-15-years-of-dangelos-voodoo/, accessed 15 March 2015.

- 12 Leeds quoted in Ibid.

- 13 D’Angelo, quoted in George interview.

- 14 “Bootsy Collins, Legendary Funk Bassist, Interviewed on the Sound of Young America.” http://maximumfun.org/sound-youngamerica/bootsy-collins-legendary-funk-bassist-interview-sound-young-america, accessed 15 March 2015.

- 15 Which is not to say black rock musicians were dormant during this period. Rather, a range of African American bands, including hardcore band Bad Brains, the punk band Death, ska-rock fusionists Fishbone, and the hard-rock outfit Living Colour (led by guitarist Vernon Reid) exemplify a wide range of engagements of black bands in rock performance from the 1970s onward that were later supported by organizations like the Black Rock Coalition (founded 1985) and the Afropunk Music Festival (founded 2002). However, it was still common for black rock bands to be denied recording contracts on the basis that they “didn’t sound black enough” in the early 1990s. Quote from an unnamed A&R executive at Atlantic Records in 1991 to Mark Brooks, then of the RGB Band. Mark Brooks, personal communication, 10 April 2015.

- 16 George interview.

- 17 George interview.

- 18 Samuel A. Floyd, The Power of Black Music (New York: Oxford, 1995), 53.

- 19 Questlove quoted in “D’Angelo’s Black Messiah, The DVD Extras: Behind The Scenes Info From Questlove, Russell Elevado, Ben Kane + More.” Okayplayer online, http://www.okayplayer.com/news/dangelo-black-messiah-dvd-extras-behind-the-scenes-questloverussell-elevado-ben-kane-alan-leeds.html, accessed 1 April 2015.

- 20 Justin Charity, “Interview: Terrace Martin Talks.”

- 21 Ibid.

- 22 Ibid.

- 23 Jay Deshpande, “Jazz Pianist Robert Glasper on His Role in Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly,” Slate online, 27 March 2015. http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2015/03/27/kendrick_lamar_s_to_pimp_a_butterfly_robert_

glasper_on_what_it_was_like.html, accessed 1 April 2015. - 24 DJ Ebro, quoted in “Kendrick says Macklemore went too far + who “i” is for & the state of HipHop,” Hot 97 interview, 3 Nov. 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tItZsMcLSRM, accessed 1 April 2015.

- 25 Lamar quoted in Ibid.

- 26 Clover Hope, “The Overwhelming Blackness of Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly,” The Muse / Jezebel online,17 March 2015. http://themuse.jezebel.com/the-overwhelming-blackness-of-kendrick-lamars-butterfly-1691770606, accessed 1 April 2015.

- 27 Adelle Platon, “Miley Cyrus Asked For a ‘Black’ Sound for Single, Says Songwriters Rock City,” Vibe online, 12 June 2013 http://www.vibe.com/article/miley-cyrus-asked-black-sound-single-says-songwriters-rock-city, accessed 1 April 2015.

- 28 Amy Wallace, “Sam Smith: The New Face of Soul,” GQ online February 2015, http://www.gq.com/entertainment/music/201502/sam-smith-new-rat-pack, accessed 1 April 2015.

- 29 Brittney Cooper, “America’s “Prince” problem: How Black people – and art – became ‘devalued,’” Salon online, 11 February 2015, http://www.salon.com/2015/02/11/americas_prince_problem_how_black_people_and_art_became_

devalued/, accessed 1 April 2015.