American Music Review

Vol. XLIV, No. 2, Spring 2015

By Mark Burford, Reed College

W.C Handy at the American Negro Music Festival. Courtesy of St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

The functions of public musical spectacle in 1940s Chicago were bound up with a polyphony of stark and sometimes contradictory changes. Chicago’s predominantly African American South Side had become more settled as participants in the first waves of the Great Migration established firm roots, even as the city’s “Black Belt” was newly transformed by fresh arrivals that ballooned Chicago’s black population by 77% between 1940 and 1950. Meanwhile, over the course of the decade, African Americans remained attentive to a dramatic narrowing of the political spectrum, from accommodation of a populist, patriotic progressivism to one dominated by virulent Cold War anticommunism. Sponsored by the Chicago Defender, arguably the country’s flagship black newspaper, and for a brief time the premiere black-organized event in the country, the American Negro Music Festival (ANMF) was through its ten years of existence responsive to many of the communal, civic, and national developments during this transitional decade. In seeking to showcase both racial achievement and interracial harmony, festival organizers registered ambivalently embraced shifts in black cultural identity during and in the years following World War II, as well as the possibilities and limits of coalition politics.

The ANMF was made possible through an earnestly committed, if circumstantially bonded, cohort of bedfellows. The event was created in 1940 by Defender executive and writer W. Louis Davis, a forty-year-old business and public relations guru with an appreciation for the “wonderful art of selling.”1 Through an array of endeavors, ranging from life insurance to his own music booking agency, Davis built a reputation as one of Chicago’s most visionary and well-connected black residents. Davis was a fierce advocate for black quality of life issues, which he and Defender colleagues believed could be furthered through more fluid dialogue between cultural production, public service, and black capitalism. The ANMF was empowered by an impressive interracial Board of Directors and amicable relations with influential local business leaders and black churches. Instrumental in festival programming was Davis’s sister-in-law Marva Louis, the glamorous and socially conscious wife of revered heavyweight champion Joe Louis.

As a Defender initiative, the festival drew strength from an activist black press flush with confidence from its expanded reach and unprecedented political access. The 1940 death of Defender founder and Booker T. Washington protégé Robert Abbott and the assumption of the paper’s editorship by his nephew John Sengstacke signaled a passing of the mantle to “a younger, post-Washingtonian generation of black and white Chicago intellectuals, journalists, entrepreneurs, activists, and cultural workers”2 for whom the Defender represented the increasingly militant face of an ambitious civil rights program. By the end of WWII, national circulation for black newspapers had risen to an all-time high of nearly two million, and as Bill Mullen has argued, well after the 1939 Hitler-Stalin pact shook the convictions of many progressives, the Defender’s pages reflected the street cred that communists maintained among many black Chicagoans for their anti-racist commitments.3 The war in Europe was another omnipresent backdrop. The ANMF was launched as a benefit for the American Red Cross’s War Relief Fund. When the U.S. military entered combat, and even after the war ended, the event continued to raise funds for various causes under the auspices of Defender Charities while remaining a vehicle for the expression of black patriotism and bolstering home front morale.

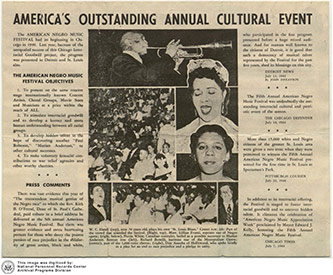

American Negro Music Festival: America’s Outstanding Cultural Event, Chicago Times, 7 July 1944, National Personnel Records Center, Archival Programs Division.

Insofar as it foregrounded Americanism, interracialism, and the spiritual as an emblem of the country’s racial and Judeo-Christian past, the ANMF can also be understood as a spin-off. The Chicago Tribune’s annual Chicagoland Music Festival, held from 1930 to 1964 at Soldier Field, regularly drew massive crowds from throughout the Midwest region. Promising to cater to all musical tastes and social classes and bringing together top professionals and amateurs identified through regional competitions, the Chicagoland Festival sought to mitigate racial strife with an event intending “to create kindly feeling between Caucasians and Negroes” through its racially mixed audiences.4 Patriotic performances and audience sing-alongs were prominently featured, though the annual highlight of the Chicagoland festival were the Negro spirituals sung by a 1,000-voice African American chorus led by the dean of Chicago’s black choir directors J. Wesley Jones. In a powerful annual climax redolent with visual and sonic symbolism, 2,000 white choristers joined Jones’s ensemble for the singing of Handel’s “Hallelujah” chorus.

Davis seemed intent to rearticulate the model and message of the Chicagoland Music Festival but from a black perspective informed by uplift ideology. In its first three years, the ANMF was held at Soldier Field but in 1943 it was relocated—perhaps emblematically—deeper into the South Side to Comiskey Park, home of the Chicago White Sox. The Chicagoland festival’s populist message was echoed in the ANMF promise to present artists who “have reached farmers, housewives and laborers through the radio, performing music as varied and beautiful as the groups that make up America.” Yet despite declaring offerings “ranging from opera to jive,” the first years of the ANMF were dominated by concert music. The wedding of classical music and the spiritual was clear in the festival’s programming of such popular religious vocal ensembles as the Southernaires, the Wings Over Jordan choir, and Jones’s mass chorus alongside classically trained African American soloists. Among early headliners were the two preeminent black male recitalists, tenor Roland Hayes and bass-baritone Paul Robeson. Marian Anderson, perhaps America’s best-known concert artist by virtue of her European triumphs and her landmark 1939 Easter Day recital on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, never appeared, though she was an honorary chairperson.

In the 1920s, Hayes, Robeson, and Anderson had pioneered the performance of arranged spirituals alongside European art songs at recitals. Because of its steady commitment to programming classical music, the ANMF presented an historically significant array of black concert and opera singers beyond the “big three,” many them younger artists, including sopranos Anne Brown, La Julia Rhea, and Muriel Rahn; Canadian contralto Portia White; tenor Pruth McFarlin; and baritones Todd Duncan, Kenneth Spencer, and Robert McFerrin, who in 1955 became the first African American man to sing at the Metropolitan Opera. In another borrowing from the Chicagoland festival, the fifth ANMF added a regional “Search for Talent” contest for aspiring black classical vocalists from Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Missouri, Kentucky, and Illinois, who competed to be among three finalists given the opportunity to perform at the festival, broadcast nationally on CBS radio. Third place at the 1947 festival talent search went to nineteen-year-old Wilberforce College student Leontyne Price. The festival’s aesthetic orientation could be discerned even in several of the jazz artists who appeared: violinist Eddie South, boogie-woogie pianist Dorothy Donegan, bandleader Marl Young, and swing harpist Olivette Miller were all classically trained musicians.

In 1945, the sixth ANMF made a notable shift. Concert music was still prominently featured—Juilliard-trained Brown, who created the role of George Gershwin’s Bess opposite Duncan as Porgy, was enthusiastically received singing “Summertime” and a Debussy aria—and the Deep River Boys and Jones’s chorus crooned spirituals. A general air of solemnity held sway during a memorial to black America’s beloved president Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who died in office just three months prior. Highlighting the tribute was the “Going Home” theme from the slow movement of Dvořák’s “New World Symphony” played by one of FDR’s favorite musicians, African American accordionist Graham Jackson. Restoring the air of festivity and stealing the show, however, was the band of vibraphonist Lionel Hampton, starring “5 feet, 3 inches, 210 pound boogie-woogie wizard of the ivories” Milt Buckner. Hampton’s set in front of a reported crowd of 25,000 spectators marked a popular turn at the ANMF, a signature moment documented by Albert Barnett’s glorious blow-by-blow description in the Defender:

But it was when the band played “Caledonia,” that caution was thrown to the wind, with a number of youths jitter-bugging up and down the broad aisles to the applause and encouragement of the fans.

A near-sensation hit the grandstand opposite right field, when a popcorn vendor, thrilled from fingertips to toes by the rocking Caledonia strain, suddenly threw his popcorn and container away and started gyrating and jitter-bugging up and down the wide steps of the grand-stand.

The youth’s performance was almost professional and before long, everybody in the park, in all tiers of seats, even those on and near the bandstand, were enjoying the spectacle, and howling encouragement to the dancing pop-corn vendor, who was finally led away by insistent police.5

Apart from the Hampton-inspired rite of passage from spirituals to swing, the festival also built its brand through appearances by such prominent black figures as Joe Louis, Mary McLeod Bethune, Langston Hughes, Pearl Bailey, Earl “Fatha” Hines, Ella Fitzgerald, and perennial favorite W. C. Handy, and by white Hollywood actors including Paul Muni and Don Ameche.

The mid-forties marked the apex for Defender circulation and the festival’s success appears to have grown along with the paper’s fortunes as in these years the ANMF reached its own zenith in visibility and prestige. This was evident in the festival’s expansion—beginning in 1944, the ANMF was “franchised,” repeating its program at Briggs Stadium in Detroit and Sportsman’s Ball Park in St. Louis—and in the remarkable degree of high level support. Letters of endorsement came from the mayors of Chicago, Detroit, and St. Louis, from the governors of Illinois, Michigan, and Missouri, and from President Roosevelt hailing the festival for recognizing the “universal” appeal of black cultural achievement. Coming on the heels of deadly race riots in Detroit and Harlem during the summer of 1943, the timing of this aggressively mobilized affirmation was surely not coincidental. All messages of support for the ANMF heavily underscored its important role in furthering black and white solidarity. Chicago Mayor Edward Kelly, who appeared annually in person to congratulate the festival for having become a “national institution,” designated the week leading up the 1945 event “American Negro Music Festival Inter-Racial Good Will Week.” Martin Kennelly took up these duties when he was elected mayor in 1947. The festival and the black musical heritage it celebrated, Roosevelt wrote to Davis, “contributed much to interracial morale on the home front” and deepened “appreciation of democracy and each other.”6

The music of black Christianity, particularly spirituals and gospel, neatly encapsulated the symbiotic virtues of ethnic difference and national cohesion. Jones, the venerable and musically conservative director of the esteemed Metropolitan Community Church choir and president of the National Association of Negro Musicians, was assisted in the direction of the mass choir by pioneering gospel songwriter Thomas A. Dorsey and singer Magnolia Lewis Butts. In 1933, Butts, Jones’s longtime associate as a soloist with his choirs and as director of the youth choir at Metropolitan, partnered with Dorsey and Theodore Frye in co-founding of the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses, which laid the institutional foundations for the modern black gospel movement. We can only speculate about whether recognition of Dorsey and Butts as co-directors of Jones’s mass chorus came with stylistic modifications or whether it simply acknowledged their standing within the South Side church music community. Regardless, the contribution of core members of Chicago’s gospel scene to the ANMF indicates the increasingly secure place of black gospel alongside the concert spiritual in the 1940s. Despite the conspicuous and curious absence of Chicago’s numerous gospel luminaries at the ANMF—for instance, the Roberta Martin Singers, the Soul Stirrers, or Mahalia Jackson, whose 1947 recording “Move On Up A Little Higher” made her a national sensation—audiences at the ninth festival heard gospel music in the popular format of a multi-city “gospel song battle.”

Yet it is difficult to know if the inclusion of gospel in festival programming in 1948 was a triumphant breakthrough or an early sign of difficulty drawing stars that resulted in the radically scaled-down community event presented a year later. In 1949, the ANMF, in its tenth and final year, was moved from the summer to the fall and from Comiskey to the Chicago Coliseum. More significantly, the suddenly and unmistakably withered lineup was a likely product of the Red Scare. Casting aspersions on civil rights activists by linking them with communism was a familiar script. As A. Phillip Randolph, National President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, observed in a 1936 editorial: “It’s gotten to be a regular indoor sport now to damn most movements and individuals who resolutely and aggressively fight for human and race rights and the rights of the workers and minority groups by branding them as ‘red.’”7 The stakes were raised, however, when on 22 March 1947 President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9835 to purge Communist influence from the federal government. Commentators quickly noted close-to-home implications for African American sociopolitical aspirations. In enforcing Truman’s so-called “Loyalty Order,” the black press observed, “FBI agents and loyalty board personnel are including reports of interracial association in the category of ‘derogatory’ information against federal workers in loyalty proceedings,” and U.S. Attorney General Tom Clark identified an array “interracial groups active in the fight for Negro civil rights” as subversives. “Communism and integration have apparently come to mean the same thing to the average white southerner,” a resigned Al Smith wrote in his Defender column.8

In such a climate, the ANMF would have been an easy target for reactionary anti-communists both within and outside of government. Particularly suspect were the festival’s motto of “interracial goodwill” and its open associations with Robeson, black actor and progressive activist Canada Lee, and American Youth for Democracy, the renamed Youth Communist League, whose chorus sang at the 1946 event and which soon landed on the Attorney General’s blacklist. Already a financial loss even during its heyday due to Davis’s expensive taste for talent and costly investment in advertising, the ANMF began to run up unpayable debts as some loyal supporters withdrew their support. When board member Whipple Jacobs’s tenure as President of the Chicago Association of Commerce ended in 1946, the Association’s endorsement was discontinued and Jacobs informed Sengstacke and Davis “I cannot authorize the use of my name on your Board of Directors in connection with further promotional activities for the festival.”9 These budgetary and political realities help explain the festival’s jarring swerve from booking “stars from the concert stage, radio, theater and music worlds” to presenting talent drawn from “south and southwest siders.” Instead of Hollywood, Broadway, and concert artists, the tenth and final ANMF in October 1949, held less than a month after the Peekskill riots mortally wounded Robeson’s career and undercut the American Left, featured community theater actors, high school bands, and a “gospel fete,” with unidentified singers, directed by Dorsey.10

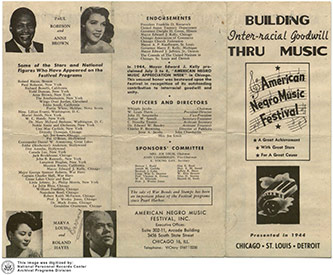

American Negro Music Festival: 1944 Program, National Personnel Records Center, Archival Programs Division.

The American Negro Music Festival was ushered in confidently on a wave of Popular Front–era interracialism, was sustained by a spirit of national unity during the “good war,” and abruptly evaporated under the gathering clouds of Cold War anticommunism. Such a summary is undoubtedly true, though it only tells part of the story. Mullen observes how Popular Front–style political coalitionism in 1940s Chicago helped buttress local civil rights activism through “the creation of an imaginary black political space” constructed by a “fantastic recombining of ideological possibilities.”11 The American Negro Music Festival was one such heterogeneous political space, bringing the goals of the black freedom struggle into close proximity with nationalist fervor, religious belief, liberal faith in the free market system, promotion of the city of Chicago, and celebrity buzz. The fate of the ANMF is a reminder of the doors to progressive collaboration that were permanently slammed shut by McCarthyism, though it is also a cautionary tale about how the necessary compromises of coalitions and the “expediency of culture” can neutralize the more radically critical edges of political activism.12 At Comiskey Park, the ante for publicly recognizing black musical achievement was a lusty celebration of American militarism.

Moreover, the feel-good ethos of interracial harmony and the safe space of culture—“through music and song the barriers of race are forgotten,” touted Defender promotion13—always harbored a risk of becoming non-threatening side streets that bypassed troubling questions that continued to face black Americans in the 1940s: anti-lynching legislation, adequate employment opportunities, equitable housing practices, and voting rights. Lastly, at a time when for some African Americans “swinging the spirituals” a la Sister Rosetta Tharpe was considered shameful cultural sacrilege, the ANMF became a form of discourse on black cultural politics, as the eventual programming of swing and gospel indicated ongoing negotiation of the place of the popular and the black vernacular within a politics of respectability. With an eye on possibilities envisioned and limitations faced, the American Negro Music Festival becomes recognizable as an episode within the history of Chicago’s festival culture that encompassed both the expansion and the constriction of black musical and political desires during a period of profound national change.

Notes

- 1 William Occomy, “Business and Commerce,” Pittsburgh Courier, 1 August 1936.

- 2 Bill Mullen, Popular Fronts: Chicago and African-American Cultural Politics, 1935-46 (Urbana and Chicago: University of

- Illinois Press, 1999), 44-74.

- 3 Ibid.

- 4 Monica Reed, “Music Festivals and the Formation of Chicago Culture,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 103 (Spring 2010): 736

- 5 Albert Barnett, “25,000 Honor FDR at Negro Music Festival,” Chicago Defender, 28 July 1945.

- 6 Letter from Franklin Delano Roosevelt to W. Louis Davis, 23 March 1945.

- 7 A Phillip Randolph, “Randolph Says Race Congress Not Communist,” Chicago Defender, February 1936.

- 8 “Clark Lists ‘Red’ Groups,” Pittsburgh Courier, 13 December 1947; Lem Graves, Jr., “Flimsy Charges Used in FBI, Loyalty Board ‘Purges,’” Pittsburgh Courier, 11 December 1948; Al Smith, “Adventures in Race Relations,” Chicago Defender, 6 August 1949.

- 9 Letter from Whipple Jacobs to W. Louis Davis, 6 March 1946; Letter from Jesse Jacobs to John Sengstacke, 8 March 1946, John Sengstacke Papers, Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, Chicago Public Library.

- 10 “Plan American Music Festival Oct. 1 in Stadium; Name Aids,” Chicago Tribune, 21 August 1949.

- 11 Mullen, Popular Fronts, 57.

- 12 George Yudice, The Expediency of Culture: Uses of Culture in the Global Era (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003).

- 13 “Overflow Crowd Expected Friday,” Chicago Defender, 26 July 1947.