American Music Review

Vol. XLIV, No. 1, Fall 2014

By Michael Weinstein-Reiman, Columbia University

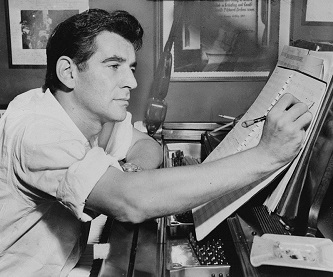

Leonard Bernstein, 1955. Al Ravenna, World Telegram. Staff Photographer - Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection.

It is impossible for me to make an exclusive choice among the various activities of conducting, symphonic composition, writing for the theater, or playing the piano. . . . What seems right for me at any given moment is what I must do.1

I am so easily assimilated.

It’s easy, it’s ever so easy!

I’m Spanish, I’m suddenly Spanish!

And you must be Spanish, too.

Do like the natives do.

These days you have to be

In the majority. . .2

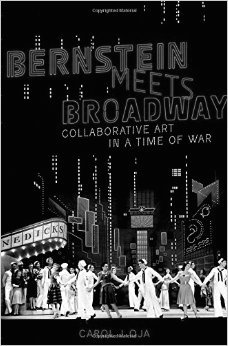

Carol J. Oja’s captivating monograph, Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War, is an expert synthesis of traditionally disparate musicological frameworks. Her text is at once a superlative narrative—one that weaves together the untold stories and broad cultural contexts of a seminal work of American musical theatre, On the Town, and its antecedent, the ballet, Fancy Free—and a thoroughgoing analytical study in American history, informed by extensive ethnography, archival research, and the author’s keen music-theoretical sensibility. As such, Oja’s book is ecumenical in methodology but singular in its historiographical pursuit; it shines a spotlight on an exceptional artistic creation, told in interlaced tales of groundbreaking visionaries, their collaborations, and their impact.

Throughout his life, Leonard Bernstein, like the thread of Oja’s monograph, deftly connected a host of musical and cultural worlds with extraordinary expertise. A ubiquitous and eclectic public figure, Bernstein had a hand in nearly every artistic milieu of the twentieth century, shaping it to fit his needs at the time. As Oja notes, with Bernstein “at the center of the action” of On the Town, he became a collaborator par excellence. However, Bernstein’s collaborative efforts frequently smacked of assimilative tendencies; he could, just as a conductor would accentuate a particular melody or motif, mold the medium and the discourse to suit his aesthetic.3

Assimilation rather than collaboration might be a more charged rubric under which we might subsume all the themes of Oja’s book, among them questions of genre, sex, race, and politics. As she demonstrates, from its understated diverse casting to its bald appropriation of musical styles, On the Town is an aspirational fusion born of a democratic impulse—an impulse that nevertheless could not be described as pluralist. In what follows, I highlight some of the overarching questions Oja seeks to illuminate in Bernstein Meets Broadway, but I do so paying special attention to assimilation as an artistic and social practice.

Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in the Time of War. Carol Oja, 2014.

Oja’s book is divided into three large sections; in the first of these, titled “Ballets and Nightclubs,” the author focuses primarily on an earlier collaboration between Bernstein and Jerome Robbins, the ballet Fancy Free. She writes: “[Fancy Free] is about transience, risk taking, and the sheer fun of popular culture. It focused on New York City, balancing high art with popular entertainment to produce a here-and-now aesthetic.”4 This balance between high and low would characterize the careers of Bernstein and Robbins, who indeed thrived on the here-and-now. In Fancy Free, the two limned the space between the charmingly banal and the fiercely forward-thinking, incorporating dance-hall moves and jazz idioms across a “remarkably broad spectrum of cultural and artistic references.”5 Crucially, in a maneuver that was partly autobiographical and distinctly modern, Bernstein and Robbins folded into Fancy Free a queer subtext, “with a primary story of boy meets girl that addressed a broad audience and a gay narrative directed to those who knew the signals.”6 Oja interfaces the details of Robbins and Bernstein’s respective romances with skillful musical analysis. For example, she connects Bernstein’s assimilation of Afro-Cuban traditions in the “Danzón” section of Fancy Free to El Salón México, the Latininspired “light” piece of Aaron Copland, Bernstein’s one-time mentor and lover.7 By positioning Fancy Free as a subtextual homage to the same-sex entanglements of their youth, in conjunction with its jazz-inspired montage,8 Oja situates the work’s eclecticism as a vital outgrowth of Bernstein and Robbins’s collaborative ethos.

On the Town grew out of this initial collaboration between Bernstein and Robbins, expanded to include Betty Comden and Adolph Green, who would come on board in 1944 as the show’s book writers and two of its principal cast. In the second large section of her monograph, “Broadway and Racial Politics,” Oja traces the genesis of On the Town, including an in-depth look at the career of Sono Osato, a Japanese-American woman who originated the role of Ivy Smith. “By the time of On the Town’s premiere,” Oja writes, “Sono personified the ways in which the show positioned itself in relation to the politics of war, yet largely stayed under the radar in doing so.”9 Indeed, born in Nebraska to a Japanese father and Irish-French Canadian mother, raised in Chicago and Europe, and trained in the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Sono naturally crossed cultural and generic boundaries, “moving from the world of ballet to that of Broadway in a prolonged by high-flying leap.”10 Sono’s jeté, however, was not accomplished without fanfare; as she was incorporated into the young, diverse, and dynamic cast of On the Town, her father, Shoji, was placed under house arrest in Chicago as part of the United States’s Japanese internment program. As Sono pirouetted across the stage each night as the “exotic Miss Turnstiles”—the All-American, though compulsively re-racialized beauty queen nextdoor—her father became the victim of wartime militancy and midcentury xenophobia.

In many ways, as Oja expertly notes, “exotic Ivy Smith” and Sono Osato—described by one African-American newspaper as “mixed, merry, and musical”11 —present tandem narratives of cultural arrogation, artistic attempts at racial pluralism that culminated in the “racial erasure” of the first post-war decade.12 With her biographies of several of the African-Americans who collaborated on On the Town, Oja wrests the production’s original “interracial roster of young dancers and actors who aimed for socially progressive theater” from its subsequent whitewashed resonance.13 Bernstein himself did not emerge from On the Town untouched by sociopolitical strife: by 1955, both he and Robbins would testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in response to a long list of supposed “subversive activities.”14 Of the 1949 feature film starring Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly (among several other luminaries), for example, Oja writes, “it is important to recognize that the ‘America’ greeted by the film was different from the place it had been when the stage show emerged. By 1949, not only had World War II been won, but the United States was entering a period of unprecedented growth and cultural ascendancy. It was also a more volatile political era, especially for left-leaning artists.”15 Indeed, where the wartime production of the Broadway show functioned as a critical nexus of multicultural frankness (and, importantly, political and sexual fluidity), its post-war iteration is the most overt manifestation of the work’s as similative qualities: white sailors in white sailor suits sing an anaesthetized score in what Oja astutely names an act of “racial retrenchment.”16

Leonard Bernstein circa 1960. Photo Courtesy of Erich Auerbach/Getty Images.

Though insightful musical references appear throughout Bernstein on Broadway, in the final section of the book, “Musical Style,” Oja takes a critical look at the score for On the Town. Oja writes, “On the Town responded . . . to left-wing agitprop, Broadway musicals with famous choreographers, modern ballet, and the most up-to-the minute forms of social dance.” It is in Bernstein’s ebullient music—and Oja’s shrewd analysis of it— that we expect to find some of the most overt examples of the composer borrowing across genres and cultures to attain a poignantly “here-and-now” sound. One such appropriation concerns Bernstein’s fusion of high art and jazz in the opening number, “I Feel Like I’m Now Out of Bed Yet.” The song, “written by a team of whites with music coded as black,” stems from a “white lineage of Broadway spirituals”—its bluesy aesthetic expanded to include modernist, less conventional phrase lengths and adventurous melodic writing.17 The beloved “Lonely Town” is a similarly eclectic offering. Oja notes that the lush, somewhat unstable harmonies of the number “convey a generalized sense of isolation,” and a break from the “disorienting violence of war.”18 This wistful setting gives way to an erotically charged pas de deux, for which Bernstein cultivated a distinctly rich, orchestral sound within the jazz idiom. “Come Up To My Place” and “I Can Cook Too,” immortalized in 1944 by the inimitable Nancy Walker (of subsequent Mary Tyler Moore Show and Rhoda fame), likewise seethe with empowered feminine sexuality, a fusion of burlesque bawdiness and operatic patter likely inspired by Bernstein’s love of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas.19 That type of overdramatized vocal delivery is caricatured in “Carried Away,” in which Claire and Ozzie trade in provocative innuendo and high art parody amidst the destruction of the American Museum of Natural History.

More veiled, though, are the musical-cultural references found in a trio of nightclub scenes in the second act of the production. In attendance at the fictive “Diamond Eddie’s,” “Congacabana,” and “Slam Bang” clubs, the five lead characters (all but Ivy Smith) witness performances of the seemingly innocuous number “I’m Blue.” In what Oja labels a “twisted racial journey,” “I’m Blue” appears in two satirical versions: a campy, “urban blues” that parodied “cheap white nightclub entertainment,” but that also notably traded in African-American musical tropes,20 and a “Latinized,” rumba-inflected number sung by a Carmen Miranda-esque character, Señorita Dolores Dolores. Unlike the 1944 original stage work, in which two different actresses, Frances Cassard and Jeanne Gordon, delivered these racialized musical offerings, in the 2014 revival of On the Town, a single actress (stage veteran Jackie Hoffman) sings both “I’m Blues” in a silly but outré assimilation of racial stereotypes. Ironically, as jazz, modernist pastiche, and cultural appropriation, this trio is where Bernstein shines best musically. “Rather than being defined by how they conformed to the parameters of a well-established genre,” Oja elucidates,

musicals were characterized by their capacity for flexibility,especially in relation to high-low qualities. While Bernstein posed this argument to characterize musical comedy in general, he was also articulating a framework for his own compositional style. In a sense, he was validating the cultural status of an aspect of his artistic life that was disdained by many of his classical-music colleagues.21

On the Town (1949). Gene Kelly/Stanley Donen.

While Bernstein on Broadway is the product of a long gestation that only happens to coincide with the 2014 Broadway revival of On the Town (Oja does not address this most recent production in her monograph), unpacking the nightclub act in the light of this ultimate assimilation presents a provocative turn. Bernstein’s Jewishness—his own status as Nisei, like that of Sono Osato—might have influenced his artistic malleability and fidelity to the here-andnow. Jackie Hoffman, widely known in Broadway circles as a purveyor of schtick, is a marker of immigrant-adjacent status; her shape-shifting presentation, from the notably Eastern European Madame Dilly, to that of Diana Dream and Dolores Dolores (in metaphysical “brown face,” no less!), is a crucial reassessment of On the Town’s initial understated colorblindness. Andrea Most notes, “The Broadway theater became [a set] on which Jews described their own vision of an idealized America and subtly wrote themselves into that scenario as accepted members of the white American community.”22 And so, the final quartet of “Some Other Time,” as Oja indicates, prefigures configurations Bernstein would rehearse in Candide’s garden and West Side Story’s idyllic “Somewhere”23: as idealized meditations on life after shore leave, brimming with optimism for social justice and true humanist collaboration.24

Carol Oja’s expansive Bernstein on Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War maps the creation of a groundbreaking work of musical theater onto its broader sociopolitical context. It does so remarkably—it is a compelling read, a compendium of rich cultural histories and previously untold stories, and as a vast resource for enthusiasts and scholars alike. The capacious footnotes and bibliography that accompany Bernstein on Broadway are testaments to its relevance to wide-reaching discourses. As thought-provoking and influential historiography, musicology, ethnography, and music theory, Oja’s book is sure to be a fixture on many bookshelves.

Notes

- 1 Joan Peyser, Bernstein: A Biography (New York: Billboard Books, 1998), 186.

- 2 Leonard Bernstein, et al. Candide: A Comic Operetta in Two Acts (New York: Boosey & Hawkes, 1994).

- 3 Carol J. Oja, Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 7.

- 4 Ibid., 12.

- 5 Ibid., 32.

- 6 Ibid., 23.

- 7 Ibid., 48.

- 8 Ibid., 51.

- 9 Ibid., 128.

- 10 Ibid., 123.

- 11 Ibid., 147.

- 12 Ibid., 186.

- 13 Ibid.

- 14 Elizabeth Crist, “Mutual Responses in the Midst of an Era: Aaron Copland’s The Tender Land and Leonard Bernstein’s Candide,” The Journal of Musicology 23:4 (Fall 2006), 489.

- 15 Carol J. Oja, Bernstein Meets Broadway, 114.

- 16 Ibid., 113.

- 17 Ibid., 169.

- 18 Ibid., 224.

- 19 Ibid., 234.

- 20 Ibid., 244.

- 21 Ibid., 278.

- 22 Ibid., 221.

- 23 Andrea Most, “‘We Know We Belong to the Land’: The Theatricality of Assimilation in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma!” PMLA 113:1 (Jan. 1998), 77.

- 24 Carol J. Oja, Bernstein Meets Broadway, 241.

- 25 Elizabeth Crist, “Mutual Responses,” 522.