American Music Review

Vol. XLIV, No. 1, Fall 2014

By Elliott S. Cairns, Columbia University

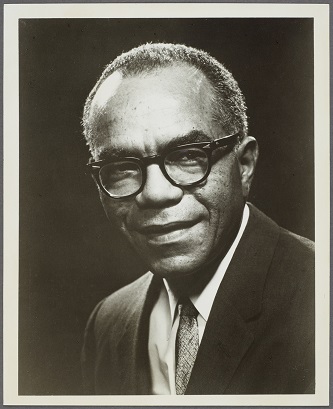

Ulysses Kay, ca. 1975. Ulysses Kay Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

It is not often that one is given the opportunity to rifle through a stranger’s belongings, especially with the aim of cataloging and arranging them. Indeed, it can at times feel intrusive, as one stumbles across old medical bills, records of tax returns, and holiday greetings; even more unsettling is the feeling that accompanies the opening of a box filled with condolence letters addressed to the family after that stranger’s death. At the same time, the experience is much like exploring a treasure trove, for each unopened box and each unopened envelope is laden with potential—one never knows what they contain, and discovery feels always imminent.

It is this kind of opportunity I was granted from 2010–11, when I became one of the first to filter through the recently deposited papers of the late African-American composer Ulysses Kay (1917–95). Kay’s papers arrived at Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML) in 2009, when Kay and his wife Barbara’s survivors—Barbara had herself died in 1997—selected it as the repository for their parents’ personal archive. In a brief essay recently published in Current Musicology, the RBML’s Curator for Performing Arts Collections Jennifer B. Lee offered a short guide to the collection, which at the time of its writing was only partially processed, and consequently, only a few items were available to researchers.1 It is exciting for me to report that the collection has been fully processed and the finding aid is complete, so it is now available in its entirety for public use with no access restrictions.2

To date, the most comprehensive resource available to scholars interested in Ulysses Kay has been Constance Tibbs Hobson and Deborra A. Richardson’s Ulysses Kay: A Bio-Bibliography, published just before Kay’s death.3 It was an invaluable tool during my time in the archive, but it quickly became apparent that this volume is only a starting point: time spent with his papers still has much to offer. Indeed, during my research for this article, I found sources that invalidate parts of the initial chronology of works I prepared while organizing the collection and working on the finding aid, so the information included here is as much a corrective for the finding aid as the finding aid was for the list of works in Hobson and Richardson’s Bio-Bibliography. The purpose of this article is not to reassess the state of scholarship on Kay, nor is it meant to rewrite his biography (it is enough for me to say that the former could benefit significantly from some scholarly attention); instead, it is my hope that this piece will serve as an introduction to this newly-available collection and reinvigorate interest in this largely overlooked African American composer. At the same time, I aim to share some of my own findings—especially with regard to the years that predate Kay’s diaries—afforded me by the extended and untypically intimate relationship I have formed with the Ulysses Kay Papers.

Born and raised in Tucson, Arizona, Ulysses Kay practiced music from a young age.4 Encouraged by both his mother and uncle—the renowned jazz musician Joe “King” Oliver—Kay studied piano, violin, and saxophone. He entered the University of Arizona in 1934, initially intending to pursue a Bachelor of Arts. He eventually switched to a Bachelor of Music during his sophomore year, studying piano with Julia Rebeil and music theory with John L. Lowell, two professors “who not only gave to [Kay] new musical insights, but also, through personal concern, helped open up a new world for this gifted young black man from the South.”5 Additionally, during the summers of 1936 and 1937, Kay met with William Grant Still, who “both inspired him and encouraged him to become a composer.”6 Upon graduating in 1938, Kay enrolled at the Eastman School of Music, where he studied composition with Bernard Rogers and Howard Hanson. In the spring of 1939, Hanson conducted the Rochester Civic Orchestra for the premiere performance of Kay’s Sinfonietta for Orchestra. Kay received his Master of Music from Eastman in 1940, after which he was awarded scholarships to study with Paul Hindemith first at Tanglewood during the summer of 1941, and then at Yale University from 1941–42.

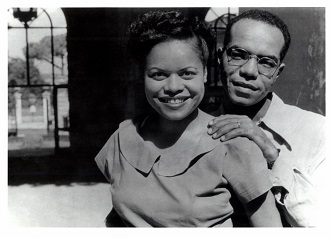

Following the United States’ entry into World War Two, Kay enlisted in the United States Navy in 1942, and was assigned to a band at Quonset Point, Rhode Island, with the rank of “Musician, Second Class.”7 While serving in the U.S. Naval Reserves, Kay continued to compose, although much of his efforts were dedicated to arranging music for naval ensembles.8 After he was honorably discharged from the Navy in 1946, Kay was awarded the Alice M. Ditson Fellowship at Columbia University, allowing him to spend the 1946–47 academic year studying composition with Otto Luening. During the summers, Kay would spend time working at Yaddo, the artists’ community in Saratoga Springs, New York, and in 1949, he relocated to Rome, Italy, with his new wife Barbara, after winning the prestigious Prix de Rome. Kay won a second Prix de Rome as well as a Fulbright Scholarship in 1951, which allowed Kay and Barbara to remain at the American Academy in Rome until 1952.

Barbara and Ulysses Kay at the American Academy in Rome, ca. 1949–52. Ulysses Kay Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

After he returned from Rome, Kay began working as an editorial advisor for Broadcast Music, Inc., a position he would hold until 1968. During the autumn of 1958, Kay, along with fellow composers Roy Harris, Peter Mennin, and Roger Sessions, was invited to travel to the Soviet Union as part of the first American delegation of composers under the new cultural exchange agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union. (The United States welcomed a similar delegation from the USSR in the autumn of 1959, which consisted of Dmitri Shostakovich, Dmitri Kabalevsky, Konstantin Dankevich, Fikret Amirov, and Tikhon Khrennikov.) During a farewell event hosted at the United Nations just before they left for their thirtyday trip, Kay expressed his wish “to see how the [Soviet] composers produce, in terms of what is expected of them.”9 Further, in a brief discussion of what Harold C. Schonberg, the New York Times reporter covering the occasion, evasively refers to as the “one problem the others will not directly face … summed up in two words: Little Rock”—viz. racism—Kay reportedly said:

“The State Department told me to speak freely and say what I think … They told me that if I speak honestly and frankly I will get further. What will I say? I will say—” and Mr. Kay stopped. “I don’t know for sure what I am going to say. Prejudice is encountered in some sections of America, not encountered in others. I worked and I studied, and I got scholarships and performances, and I’m an example. I’ll just try to explain things as I see them.”10

The visit built to a climactic concert of works by the American composers performed by the Moscow State Radio Orchestra in Tchaikovsky Hall on October 15. Approximately fifteen hundred people filled the sold-out concert hall, among them the United States Ambassador and his wife. While abroad, Kay reached out to the USSR’s Union of Composers, leaving a few of his scores behind for the perusal of its membership. The following summer, Kay received a letter from a Mr. S. Aksyuk writing on behalf of the Union of Composers, which speaks to the admiration “a number of Soviet composers and musicologists” had for Kay’s music:

In the unanimous opinion of our colleagues your works are characterized by great mastery. Especially noticeable is the wonderful use of polyphony and the various ways in which you employ it originally and inventively. In particular, the fugue fragments in the second part of the Symphony [in E] leave no doubts that in this area of composition you are an original master. In several selections with the general keenness of the sound, the separate themes are distinguished by clarity and even lyricism, e.g., in the third movement of the symphony. We are very sorry that we did not have the opportunity to hear your works in orchestration. Acquaintance with the parts, however, already permits judging the inventiveness of the orchestration, imparting brightness and keenness of sound to the complex polyphonic fabric.11

American Composer Delegation in the U.S.S.R., 1958. From left to right: Ulysses Kay, Peter Mennin, Roy Harris, and Roger Sessions Ulysses Kay Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

Kay’s teaching career began in the summer of 1965, when he accepted visiting professor positions at first Boston University, and then at the University of California at Los Angeles. Kay left his position at BMI in 1968—he continued to act as a music consultant—in order to join the faculty of Lehman College of the City University of New York. He was appointed a Distinguished Professor of Music there in 1973, and held that position until his retirement in 1989. A number of congratulatory letters on the occasion of his retirement are held in the Kay Papers, chief among them letters from Milton Babbitt, Leonard Bernstein, John Corigliano, George Crumb, Lukas Foss, Jessye Norman, William Schuman, and Otto Luening.12

One of Kay’s earliest compositional successes was Of New Horizons, a work commissioned by the American conductor Thor Johnson, whom he had met during his time at Quonset Point. As the biographical note from a program for a later performance of the work informs us, Johnson asked Kay “to write a ‘lively and optimistic piece’ for the young people of the National High School Orchestra at Interlochen [Michigan]. The resulting composition was Of New Horizons, the title of which was suggested by Mr. Johnson and which was accepted by Mr. Kay because it was ‘in keeping with the “spirit” of the music.’”13 This performance never came to pass, and instead, the work received its premiere by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra with Johnson at the podium on 28 July 1944 in the Lewissohn Stadium, which then stood on the grounds of the City College of New York. Almost two years later, the work was awarded First Prize in the orchestral division at the First Congress of the Fellowship of American Composers, where it was performed on 10 May 1946 by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Valter Poole.14 The following year, a performance of Of New Horizons by the Juilliard Orchestra again with Thor Johnson marked Kay’s Carnegie Hall debut, the work included on a program along with the New York premiere of Aaron Copland’s Letter From Home.

On 29 January 1947, an unsigned article in the New York Times announced Kay’s receipt of First Prize in the Third Annual George Gershwin Memorial Composition Contest for his A Short Overture, an award he shared that year with Earl George. In addition to the joint $1000 prize, the co-winners had their music performed at a concert on 31 March 1947 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, with Leonard Bernstein leading the New York City Symphony Orchestra.15 “Music is non-sectarian,” the mission statement of the Gershwin Memorial Contests and Concerts reads. “Its appeal and creation is not the property of any one race or religion or nationality.\

So this contest is open to all young men and women, whatever their religion or circumstance in life. When the manuscripts are judged it is the music alone which is searched; not the name or the antecedents of the composer.”16 The 1947 contest was judged by Leonard Bernstein, chairman, Marc Blitzstein, Aaron Copland, and William Schuman, with Serge Koussevitzky as honorary chairman, and Rabbi Judah Cahn as judge ex-officio.

Ulysses Kay Welcoming Delegation from the U.S.S.R., 1959. From left to right: Ulysses Kay, Dmitri Kabalevsky, Tikhon Khrennikov, Dmitri Shostakovich, Boris Yarustovsky, Konstantin Dankevich, and Fikret Amirov Ulysses Kay Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

In November of the same year, Kay’s music would feature in the first concert of the Cosmopolitan Symphony Society of New York, an “interracial instrumental ensemble … including several women players” established by Everett Lee in 1947,17 and recently discussed in these pages by Carol J. Oja.18 Kay’s Five Mosaics (1940) was heard alongside works by Rossini, Beethoven, Verdi, Schumann, and Kabalevsky—notably, his was the only piece performed by a black or American composer.19 It is fitting that this first performance at City College’s Great Hall—even if not the symphony’s “formal” debut—was presented by the Grace Congregational Church in Harlem, a church that “tolerates, by stated policy, no barriers between people.”20 “It is therefore a privilege and an honor to us,” states a note on the rear of the concert program, “to be able to present this Symphonic Society, this one harmonious orchestra of many races. Their non-racial character bespeaks that way of life which, in public endeavors and in institutional life, will dispel our pagan and insane national divisiveness, our immoral ghettoism, our psychological estrangements and fears.”21 Lee programmed a second work by Kay for the formal debut of the Cosmopolitan Symphony on 21 May 1948 at Town Hall, a concert venue in midtown “noted,” as Oja writes, “for its egalitarian policies.”22 Again, Kay was the only non-European composer to appear on the program, this time represented by his Brief Elegy for solo oboe and string orchestra, which Noel Straus, in his coverage for the New York Times, described as “likeable, and immediate in its appeal, having a well-sustained mood of tender melancholy and a prevailing poetry in its favor.”23

Although accounting for only a few folders, another fascinating inclusion in the collection are the personal papers of Ulysses’ wife Barbara. While Ulysses occupied himself with composition and working for BMI, Barbara became involved in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. Although she would spend much of her time advocating for racial equality in the Kays’ hometown of Englewood, New Jersey, Barbara made a number of trips to the American South, including one to participate in the Mississippi Freedom Rides during the summer of 1961. While there, she was arrested, and ultimately sentenced to a $200 fine and four months in prison for “Breach of the Peace.”24 A newspaper article explains that Barbara “was among five persons arrested here [in Jackson] for challenging segregation in a bus station after a ride from Montgomery, Ala.”25 However, it is in the first of the two letters she sent to Ulysses after being arrested—this one while she was awaiting transfer from Hind’s County Jail to the maximum security unit of the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman—that offers a more telling account of events:

There were five of us, three white male students, two from the U[niversity] of Chi[cago], … and one from Duke Univ[ersity] a negro male student, and myself. We met in Montgomery, Alabama, and left on the bus for Jackson. We changed buses in Meridian. Police cars escorted us into and out of each city. Our bus was almost empty, the other passengers being routed on newer Trailways buses, with toilets, although we had bought tickets in Montgomery which were to take us non-stop (eight hour ride) to Jackson. Upon entering the bus terminal at Jackson we were immediately arrested, after we refused to leave. It took 5 minutes[.] Police were everywhere. The paddy wagon was waiting.26

Following her release, Barbara participated in the Englewood Movement—the first “sit-in” in the North in which “Englewood residents took over city hall to protest racial segregation in the school”—and led a “Freedom School” in the basement of the Kay home during the subsequent boycott of Englewood schools.27

She returned to Mississippi in 1966 to participate in James Meredith’s March Against Fear, all the while working with the New Jersey chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). She recounted much of her experience during an oral history interview in 1979, which is held by Columbia University’s Center for Oral History and is available for consultation.28

Ulysses Kay attracted scholarly attention as early as 1957, when musicologist and conductor Nicolas Slonimsky penned a brief, but extremely detailed, assessment of Kay’s then two-decade-long compositional career for the American Composers Alliance Bulletin. In the opening paragraph of the article Slonimsky notes:

[Kay] is not automatically satisfied with every piece [of music] he writes, simply because it is his. Some of his music causes him acute embarrassment for no more specific reason than his detachment from that particular phase of his work. Some of the material he rejects is of excellent quality and it would be a pity if he would physically destroy the manuscripts. He has not been driven to that yet but he keeps such compositions unpublished and does not offer them for publication.29

It is indeed fortuitous that Kay would continue the practice of holding on to his compositions, published or no, for they now stand together as what is perhaps the “gem” in his Papers, in the form of a nearly-comprehensive collection of his scores and sketches. These documents account for his output between 1939 and 1988, with the bulk representing those years after the end of the Second World War. Evidence of his compositional process is wonderfully preserved: Kay was an adamant sketcher—sometimes completing a number of sketch drafts before beginning to orchestrate—and with few exceptions, these materials are all housed at the RBML, his diaries functioning as a very detailed guide.

While processing his scores, I uncovered a number of manuscripts and sketches for compositions that were documented neither in his diaries (mostly because they predated them), nor in Hobson and Richardson’s Bio-Bibliography, which itself relies heavily on Slonimsky’s list of works for those composed in 1956 or before.30 As a result, I have created a corrected list of works to serve as an appendix to this article, in which I have established a revised chronology as well as a comprehensive representation of his total output known to date. It should be consulted in union with Hobson and Richardson’s text, as much supplementary information is contained there.

A mere glimpse at the finding aid or any secondary literature about Ulysses Kay—especially the entry about him on Grove Music Online—will reveal that there is still much to be done if the story of this man, “one of the important American composers of his generation and … the leading black composer of his time,” is to be rightly told.31 In celebration of the collection coming to Columbia University, Jennifer B. Lee has curated an online exhibition, in which visitors may examine many of the documents that comprise the Ulysses Kay Papers—including some referenced here—and I encourage all to explore it.32 Of course, much is absent from the exhibition and there is still much to uncover,33 but it is my sincerest hope that now his Papers are available for consultation, scholars will seek to incorporate Kay and his music much more into our account of twentieth-century American music, one that will be inevitably enriched by doing so.

Notes

- 1 See Jennifer B. Lee, “Ulysses Kay Special Collection: Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University,” Current Musicology 93 (Spring 2012): 141–45.

- 2 Consult the finding aid for the Ulysses Kay Papers (UKP) online at: http://findingaids.cul.columbia.edu/ead/nnc-rb/ldpd_7341105/.

- 3 Constance Tibbs Hobson and Deborra A. Richardson, Ulysses Kay: A Bio-Bibliography (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994).

- 4 Much of the following biographical information is indebted to Hobson and Richardson, Ulysses Kay; and Nicolas Slonimsky, “Ulysses Kay,” American Composers Alliance Bulletin 7/1 (Fall, 1957): 3–11.

- 5 Robert D. Herrema, “The Choral Works of Ulysses Kay,” Choral Journal 11 (December, 1970): 5.

- 6 Eileen Southern, Biographical Dictionary of Afro-American and African Musicians (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982), 226.

- 7 Naval Service Records; 1942–1946. Ulysses Kay Papers, Box 84/Folder 5, Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML), Columbia University Library.

- 8 A number of previously undocumented arrangements and compositions from this time surfaced during my time processing the UKP. See the appendix to this article for a complete list of Kay’s musical output.

- 9 Harold C. Schonberg, “Exchange Composers: Harris, Sessions and Kay Discuss Their Forthcoming Trip to Soviet Union,” New York Times, 21 September 1958.

- 10 Ibid.

- 11 Translation of a letter from S. Aksyuk; 30 June 1959. UKP, Box 84/Folder 15, RBML, Columbia University Library.

- 12 Congratulatory Letters; 1989. UKP, Box 94/Folder 13, RBML, Columbia University Library.

- 13 Program for concert of Columbus Philharmonic Orchestra; 4 March 1947. UKP, Box 4/Folder 60, RBML, Columbia University Library.

- 14 Program of the First Congress, Fellowship of American Composers 6–10 May 1946. UKP, Box 4/Folder 59, RBML, Columbia University Library.

- 15 This was not the first encounter Kay had had with Bernstein. Bernstein played the piano part during the premier performance of Kay’s Sonatina for Violin and Piano on 24 January 1943 at a concert of the League of Composers, with Stefan Frenkel on violin.

- 16 Program for the Third Annual Gershwin Memorial Concert, 31 March 1947. UKP, Box 4/Folder 60, RBML, Columbia University Library.

- 17 N.S. [Noel Straus], “Symphony Group in Formal Debut,” New York Times, 22 May 1948.

- 18 Carol J. Oja, “Everett Lee and the Racial Politics of Orchestral Conducting,” American Music Review 43 (Fall 2013): 1–7.

- 19 This was in fact not the premiere of Five Mosaics, as Oja states on page 4 of her article; Five Mosaics was first performed by the Cleveland Philharmonic Orchestra on 28 December 1940, conducted by F. Karl Grossman. As such, the program for the 9 November 1947 concert is incorrect in referring to the performance as the “World Premiere.” See Slonimsky, “Ulysses Kay,” 7.

- 20 Program for concert of the Cosmopolitan Symphony Society of New York, 9 November 1947. UKP, Box 4/Folder 60, RBML, Columbia University Library

- 21 Ibid.

- 22 Oja, “Everett Lee,” 4.

- 23 N.S. [Noel Straus], “Symphony Group.” Straus is incorrect when he writes that this was the “first hearing” of Brief Elegy, as it was premiered just twelve days prior by the National Gallery Orchestra at the National Gallery of Art under the direction of Richard Bales. The program for the evening’s concert is likewise inaccurate. See Slonimsky, “Ulysses Kay,” 8.

- 24 See Barbara Kay’s sentencing receipt from Hinds County Jail in Jackson, MS, 1961. UKP, Box 82/Folder 2, RBML, Columbia University Library.

- 25 “Bergen Woman Jailed in Ride,” 3 July1961. UKP, Box 82/Folder 2, RBML, Columbia University Library.

- 26 Letter from Barbara Kay to Ulysses Kay, 7 July 1961. UKP, Box 85/Folder 9, RBML, Columbia University Library.

- 27 Lee, “Ulysses Kay,” 143.

- 28 Consult the record for Barbara Kay’s interview at: http://oralhistoryportal.cul.columbia.edu/document.php?id=ldpd_4076977.

- 29 Slonimsky, “Ulysses Kay,” 3.

- 30 Ibid., 7–11.

- 31 Southern, Biographical Dictionary, 227.

- 32 Consult the online exhibition at: https://exhibitions.cul.columbia.edu/exhibits/show/kay.

- 33 Contained in the Papers are, for instance, Kay’s correspondence with Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, Ralph Ellison, Howard Hanson, Paul Hindemith, Langston Hughes, Otto Luening, Nicolas Slonimsky, William Grant Still, and Virgil Thomson.