American Music Review

Vol. XLIV, No. 1, Fall 2014

By Ray Allen, CUNY Brooklyn College

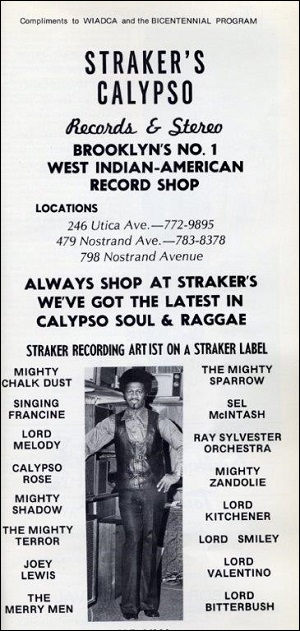

Granville Straker in his store in Brooklyn, 1975

The emergence of soca (soul/calypso) music in the 1970s was the result of musical innovations that occurred concurrently with a conscious attempt by the Trinidadian record industry to penetrate the bourgeoning world music market. The latter move was prompted in part by the early-1970s international success of Jamaican reggae and coincided with the rapid growth of diasporic English-speaking Caribbean communities in North America and Europe—sites which promised new production and marketing possibilities for the music. Brooklyn’s Caribbean neighborhoods, which had rapidly expanded in the wake of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, became popular destinations for singers, musicians, arrangers, and record producers. Some lay down roots while other became transnational migrants, cycling back and forth between Brooklyn and their Caribbean homelands to perform and record the new soca sound. Frankie McIntosh, music director and arranger for the Brooklyn-based Straker Records label, was a key player in the transformation of Trinidadian calypso to modern soca during this period.

Before turning to the story of McIntosh and Straker Records a brief review of the stylistic characteristics of soca and the critical reception the new music received is in order. By the late 1970s the term “soca” (“so” from soul music, “ca” from calypso) was used in reference to a new style of Caribbean music that blended Trinidadian calypso with elements of African-American soul, funk, disco, R&B, and jazz.1 According to ethnomusicologist Shannon Dudley, soca is differentiated from calypso by its strong, 4/4 rhythmic structure with accents on the second and fourth beats of each measure; emphasis on a syncopated bass line that often incorporates melodic figures; and fast, often frenetic, tempos. In contrast calypso pieces are based on a two-beat structure that emphasizes a steady bass line and generally exhibit slower tempos. In soca the voice and instruments tend to interlock to form a repetitive rhythmic groove, while in calypso the vocal line is more melodic and prone to improvisation as the text unfolds in a linear, verse-chorus from. Soca lyrics tend to be party oriented, with short, repetitive phrases exhorting listeners to engage in provocative, playful dance, while traditional calypso songs feature text-dense lyrics filled with witty and occasionally ribald social commentary. And finally soca arrangements often feature synthesizers, electric guitars, and additional electronic sounds for timbral effects which were considered highly inventive in the 1970s.2

Frankie McIntosh at work, Brooklyn, NY

Not all Trinidadian musicians and critics were enamored by this new soca sound or its means of production and distribution. Some worried publically that the commercialization of traditional calypso through the incorporation of what they identified as “foreign” popular styles—specifically elements of American soul, funk, and R&B, and Jamaican reggae—would compromise the integrity of Trinidad’s most distinctive musical expression. Moreover, production and distribution of the music might fall to North American and British record companies who would reap the lion’s share of the profits. Distinguished Trinidadian literary critic Gordon Rohlehr, while stressing calypso’s long history of self-reinvention, captured the concerns of many when he warned that the new soca ran the danger of embracing the “ethos of popular music” and becoming “a kind of fast food, mass-produced, slickly packaged and meant for rapid consumption and swift obsolescence.”3

The venerated calypsonian Hollis “Chalk Dust” Liverpool, known for his biting satirical calypsos, decried the commercialization and degradation of the art form. In his 1979 song “Calypso Versus Soca” he exhorted his fellow calypsonians to beware of foreign markets and to hold on to their native culture:

If you want to make plenty money and sell records plenty here

and overseas.

Yes, well plan brother for de foreigner,

compose soul songs and soca doh half lease.

But if you are concerned about your roots,

anxious to pass on your truths to the young shoots dem youths,

and learn of the struggle of West Indian Evil.

If so, yuh got to sing calypso.

Several years later the calypsonian Willard “Lord Relator” Harris raised the specter of cultural imperialism, grousing over the expansion of overseas soca record production in a song aptly titled “Importation of Calypso”:

The music that you jump to and play mas today,

is now mass produced in the USA.

It is a bad blow,

for Trinidad and Tobago.

The records will show,

we are now importing our own calypso.

Rohlehr, Liverpool, and Relator’s concerns were, on one hand, well founded, given the way the so-called “calypso craze” had played out in in the 1950s under the control of United States recording companies that favored watered down, pop arrangements by American singers over songs performed by native Caribbean calypsonians.4 On the other hand, this perspective does not adequately take into account developments in the growing Caribbean overseas communities, particularly those in Brooklyn that in the 1970s spurred the growth of soca. In contrast to the situation in the 1950s, the soca singers, musicians, and arrangers of the 1970s and 1980s were originally from Trinidad (or adjacent islands), not North America. Equally important, the influential Brooklyn-based record companies were owned and operated by Caribbean migrants and the core audience for the music consisted almost exclusively of Caribbean people living in Brooklyn, in other overseas communities such as Toronto or London, or in the Caribbean homelands.

One of these pioneering record producers was Granville Straker (b. 1939), a native of St. Vincent, who migrated to Brooklyn via Trinidad in 1959. After renting a storefront and opening up a car service at 613 Nostrand Avenue in the heart of Brooklyn’s Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood, he pursued his dream of selling records. In addition to his mainstay of American R&B and soul music he began to import Caribbean music from the Samaroo and Telco companies in Trinidad and the WIRL label in Barbados. As Brooklyn’s Caribbean community grew so did demand for calypso, and by the early 1970s Straker had three stores in central Brooklyn. In 1971 he began releasing 45s on his own Straker’s Records label, and over the next two decades built an impressive catalogue that included such calypso/soca luminaries as Shadow, Chalk Dust, Calypso Rose, Lord Melody, Black Stalin, Winston Soso, Singing Francine, Lord Nelson, and Machel Montano. Straker became a veritable one-man operation—talent scout, recording/mixing engineer, record distributor, and concert promoter.5

Straker’s recording and production process quickly evolved into a transnational project. In addition to befriending expatriate calypsonians in Brooklyn he travelled to Trinidad in search of talent in the calypso tents during Carnival season, eventually opening up two record stores in Port of Spain. He would record in either Brooklyn or Trinidad, depending on where a calypsonian was based, or when a particular artist might be visiting New York. With the advent of multi-tracking, sections of a single recording were often done at both locations (for example the horns and rhythm section in a Trinidad studio, the final vocals in a Brooklyn studio). The final mix was almost always completed in a Brooklyn or New York City studio, which, by the early 1980s, offered more sophisticated mixing boards with twenty-four track capability. As word of New York’s superior recording and mixing facilities spread, more singers and musicians came north to record.

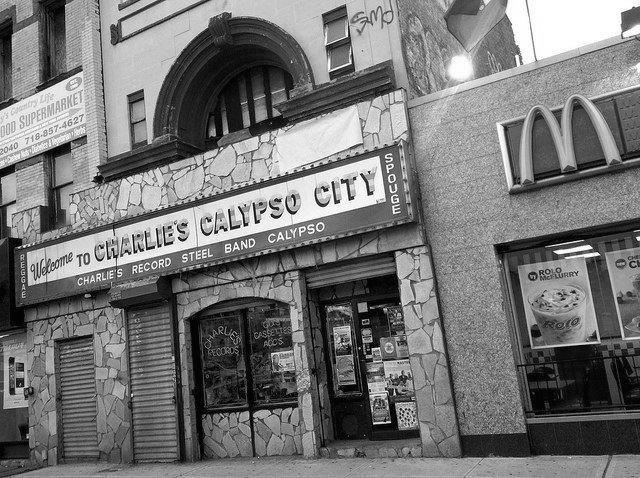

A second important Brooklyn-based record producer and Straker’s main rival was Rawlston Charles (b. 1946), a native Tobagonian who arrived in New York in 1967 with a suitcase under one arm and a Lord Kitchener album under the other. In 1972 he opened a record shop at 1265 Fulton Street in Brooklyn, and the following year began to issue records on his own Charlie’s Records label. Over the next decade Charles helped produce and distribute some of the most important early soca recordings including Calypso Rose’s “Give me Tempo (1977, arranged by Pelham Goddard, recorded in Trinidad and New York, mixed in New York), Lord Kitchener’s landmark “Sugar Bum Bum” (1978, arranged by Ed Watson, recorded in Trinidad and mixed in New York) and Arrow’s international super hit “Hot, Hot, Hot” (1983, arranged by Leston Paul, recorded/mixed in New York). His catalogue would grow to be a who’s-who of calypso and soca in the late 1970s and 1980s, including recordings by the aforementioned Rose, Kitchener, and Arrow, as well as those by Sparrow, Shadow, Melody, Duke, David Rudder, and many others. In 1984 he built his own recording studio above his Fulton Street record shop which became a hub of activity for Caribbean musicians visiting Brooklyn. Like Straker, Charles possessed an exceptional ear for talent and a willingness to embrace the emerging soca sound in hopes of appealing to a broader international audience without losing his core Caribbean followers.6

Charlie’s Calypso City, 1241 Fulton Street, Brooklyn, NY

Straker and Charles worked with a number of prominent Trinidadian music arrangers, including Art de Coteau, Ed Watson, Pelham Goddard, and Leston Paul, all of whom spent considerable time in New York. But pianist and arranger Frankie McIntosh, who in 1978 became Straker’s musical director, left the most distinctive stamp on Brooklyn’s soca sound. Born in Kingstown, St Vincent in 1946, McIntosh had the benefit of piano lessons and as a young boy played in his father Arthur McIntosh’s dance orchestra, the Melotones. The band played primarily instrumental dance orchestrations of calypso, Latin, and American standards, but members gathered at the McIntosh home on Sunday afternoons for jazz jam sessions.The Senior McIntosh, a saxophonist, idolized Illinois Jacquet, Charlie Parker, and Lester Young. After graduating high school and teaching in Antigua for two years, McIntosh migrated to New York and began studying music at Brooklyn College in 1968. While earning a bachelor’s degree in music at Brooklyn and an MA in music at New York University, he played keyboards with several Caribbean and American R&B groups, and jammed with NYC jazz musicians Jimmy Tyler, Donald Maynard, Snug Mosely, Jean Jefferson, and others.7

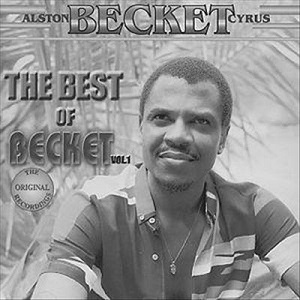

In the summer of 1976 Alston Cyrus, a St. Vincent calypsonian with the stage name Becket, approached McIntosh about tightening up some of his calypso arrangements for an upcoming Manhattan boat-ride engagement. By the 1970s most calypsonians (or their record producers) employed arrangers to compose and score out horn and bass lines as well as the basic chordal progressions for guitar and keyboard. Musicians were expected to sight read charts that were passed out at recording sessions and live performances. The horn lines were deemed central to the arranger’s craft and an essential component of a song’s potential popularity.

The two Vincentians hit it off, and shortly after McIntosh arranged his first calypso recordings for Becket’s Disco Calypso album. Recorded in 1976 and released the following year on the American Casablanca label, the album did not sell well in North America, but one song, “Coming High,” was popular in Trinidad, St. Vincent,and Brooklyn. The song was originally titled “Marijuana,” but producer Buddy Scott insisted that the title be changed to “Coming High” and that Becket alter the phrase “Marijuana” to the non-drug but sexually suggestive line “Mary do you wanna?" Musically “Coming High” demonstrates key characteristics of early soca: the foregrounded melodic bassline that occasionally doubles the vocal; the prominence of the synthesizer; the compact, repetitive text; and the lengthy break/groove sections in the middle and end of the piece. These rhythmic break sections (3:25-4:00; 7:22-end), built around the breaking down and rebuilding of the instruments and fundamental riffs, were similar to those heard on popular African American funk, soul, and disco recordings of the period. Their inclusion extends the piece to dance-friendly 8:22 length. In addition McIntosh introduces innovations seldom heard in calypso or early soca. Following the initial two verses and choruses he modulates up a half step (from B Flat to B) into a jazzy sounding bridge with the synthesizer trading riffs with the double-voiced horns and bass (1:55) before cycling back down to the original key of B flat. Later in the piece he brings in a bluesy guitar solo (5:35-6:15) by Victor Collins which flows into another set of horn riffs and a final modulation and bridge. [See YouTube links at the end of the article.]

Becket LP Cover

The following year, 1978, Becket and McIntosh teamed up for a second recording. The LP Coming Higher included the song “Wine Down Kingstown,” a reference to Carnival festivities in the St. Vincent capital. The prominent bass and synthesizer lines, the rapid tempo, the extended percussion break/groove sections, and Becket’s exhortation for listeners to “wine down” (dance) place the piece squarely in a soca vein. But as in “Coming High,” jazz and blues elements are clearly evident. The piece opens with a syncopated, choppy horn line alternating between the reeds and the brass. The vocal chorus (0:40) ends with a cycle of fourths moving from C back to the tonic F# chord—a common jazz progression but unusual for calypso or soca. The arrangement is further enlivened by a bop-inflected twenty-four-bar solo played by African American trumpeter Ron Taylor (2:58) and McIntosh’s semi-improvised synthesizer figures over punchy horn riffs (3:20). The piece ends on an extended groove section with the horns blasting out a dominant-seven-sharp-nine chord (6:30), a dissonant voicing associated more with Latin jazz or rock than calypso.

In 1978 Straker approached McIntosh about arranging for his label, and the two would go on to forge a musical alliance that would last for decades. McIntosh became musical director for Straker’s Records, organizing the studio band (often under the name of the Equitables) and arranging for dozens of Straker’s calypsonians, including Chalk Dust, Shadow, Calypso Rose, Winston Soso, Poser, Lord Nelson, Singing Francine, Duke, and King Wellington.

As the music moved into the 1980s he distinguished himself through his innovative horn lines and synthesizer figures, although few of his arrangements reached the harmonic sophistication of the earlier pieces done in collaboration with Becket. McIntosh admits that there was pressure from the market to stick to more standard one-four-five triadic chord progressions and simplified melodies with less improvisation and more emphasis on repetitive dance loops:

Everyone wanted a hit like Kitchener’s “Sugar Bum Bum” (1978). And in order to sound like“Sugar Bum Bum” you had to leave out the sevenths and raised ninth chords. You just played simpler things, more accessible to the ear. Harmonies were in decline, in a sort of state of attrition.8

Despite these trends McIntosh continued to produce imaginative arrangements that maintained a degree of spontaneity. For example, Hollis “Chalk Dust” Liverpool’s 1983 recording for Straker Records, “Ash Wednesday Jail,” is an up-tempo soca romp with forceful horns, slinky synthesizer fills, and a melodic bass figure that occasionally doubles the horns lines and vocals. Halfway through the piece McIntosh enters with a sixteen-bar improvised solo (3:08) using a steel pan sound programmed though his Prophet 5 synthesizer. He recalls having to convince Liverpool to increase the tempo of his original song to create a stronger soca groove. Though skeptical at first, the singer was quite satisfied with the final arrangement which turned out to be one of his most popular recordings. His earlier misgivings regarding soca notwithstanding, Liverpool was willing to embrace elements of the new music as long as his lyrical text remained intact.

Liverpool remembers McIntosh being much freer in the studio than older arrangers like Art De Coteau. He allowed musicians and singers more input, modifying arrangements on the spot during sessions, and in general leaving room for modest embellishments and improvisation.9 McIntosh echoed this assessment:

Oh yes, even when I go to a full score, it’s never like this is written in stone and we must stick to this. From the first date, if we are playing the rhythm section and I don’t think a chord works I will change it. Or I would change the horn line or the bass line in a flash … I was quite open to ideas, as long as they worked. So in the studio we might be playing a chart, and someone like (trumpeter) Errol Ince might say “Frankie, do you mind if we do this instead?” I’d say play it and let me hear it. And if I liked it I’d say “bang, go for it!” Then I’d change the music.10

In sum, McIntosh brought a more flexible, jazz-influenced sensibility to the studio. The Equitables were cosmopolitan in make-up, composed of musicians from Trinidad, St. Vincent, Barbados, Panama, Puerto Rico, and the United States. Many had diverse musical backgrounds that included experience playing jazz, Latin, R&B, soul,and funk.

When asked if there was a distinct Brooklyn soca sound in the late 1970s and 1980s McIntosh answered cautiously:

In Brooklyn we never set out to create a New York or Brooklyn sound, we just played from whatever experiences we had as Caribbean people here in New York, as an artistic expression. But listening back to it now I do hear some subtle differences. I would say the calypso up here would have been more influenced by jazz and R&B. In Trinidad and St. Vincent and Grenada it was more what they would call rootsy … Because of the experience and the musical background of the people here in Brooklyn … the recordings in Brooklyn were different from the recordings in Trinidad. It was a natural consequence of artistic expression, based on experience.11

The rise of soca in Brooklyn’s Caribbean community, like many forms of diasporic expression, was the result of a complex entanglement of demographic, economic, artistic, and cultural/political factors. It was a movement made possible by the collective efforts of dozens of musicians, producers, and arrangers, as well as thousands of music fans, who settled in Brooklyn but who continued to travel regularly back and forth between New York and their Caribbean homelands. But it also required the energies of individual visionary cultural entrepreneurs like Straker and Charles, and forward-thinking arrangers like McIntosh, who harnessed New York’s diverse Caribbean musical currents at a moment when older calypso forms were ripe for stylistic transformation. They remained in close contact with their home cultures, and in terms of agency and aesthetics maintained a core allegiance to calypso, the essential form of Trinidadian Carnival music. At the same time they demonstrated an openness to outside musical influences, particularly African American R&B, funk, soul, disco, and jazz, and a willingness to embrace, and even encourage, stylistic innovation. Although they never achieved the international success of their reggae competitors, they did manage to keep the production and distribution of their music within a Caribbean network, a stark contrast to the North American hegemonic domination of the industry during the 1950s calypso craze. Lord Relator was correct when he asserted in 1983 that much calypso was produced in North America, but the profits—meager as they may have been—remained largely within the transnational Caribbean community.

All this is not to suggest that soca would not have happened had there been no Caribbean diaspora, or that musical activity in Brooklyn superseded that in Trinidad. Indeed further comparative work will be necessary to define the distinct nuances of the Brooklyn-style soca that McIntosh, Straker, and Charles helped nurture in the 1970s and 1980s. However, it is safe to conclude that the stylistic development and economic viability of soca was notably enhanced by activity in the diaspora, particularly by developments in Brooklyn. Evolving in the context of an ongoing two-way cultural interchange, soca is best understood as a transnational expression anchored in Trinidadian tradition but indelibly shaped by overseas musical influences.

Notes

- 1 For more on the origins of soca see Jocelyn Guilbault, Governing Sound: The Cultural Politics of Trinidad’s Carnival Musics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 172-177.

- 2 Shannon Dudley, “Judging ‘By the Beat’: Calypso versus Soca.” Ethnomusicology 40 (Spring/Summer 1996): 269-298.

- 3 Gordon Rohlehr, A Scuffling of Islands: Essays on Calypso (San Juan, Trinidad: Lexicon Trinidad, 2004), 11.

- 4 Harry Belafonte was at the forefront of the rise of popularity of calypso music in the United States in the 1950s, a phenomenon journalists labelled “the Calypso Craze.” Belafonte was born in New York of Jamaican parentage, but had little direct experience with Trinidadian-style calypso or other forms of Carnival music (Jamaica, at that time, had no Carnival tradition, and calypso was the providence of Trinidad and the adjacent Lesser Antilles islands). Belafonte, whose most popular songs were recorded for RCA Victor, was not considered a genuine calypsonian by most Trinidadians. Although handful of Trinidadian calypsonians who spent time in New York during the 1950s did benefit indirectly from Belafonte’s rising star, it was North American performers, ranging from jazz singers Louis Armstrong and Nat King Cole to pop singers Rosemary Clooney and the Mills Brothers to popular folk acts like the Tarriers, the Easy Riders, and the Kingston Trio, who received the most attention from American records companies. For more on the Calypso Craze see Ray Funk and Donald Hill, “Will Calypso Doom Rock’n’Roll?: The U.S. Calypso Craze of 1957” in Trinidad Carnival: The Cultural Politics of a Transnational Festival, edited by Garth Green and Philip Scher (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003), 178-197; and Calypso Craze, 1956-1957 and Beyond, CD/DVD set and booklet, edited by Ray Funk and Michael Eldridge (Bear Family Records, 2014).

- 5 Granville Straker, interview by the author, Brooklyn, NY, 18 July 2013.

- 6 Rawlston Charles, interview by the author, Brooklyn, NY, 17 September 2013.

- 7 Frankie McIntosh, interview by the author, Brooklyn, NY, 23 July 2013.

- 8 Ibid.

- 9 Hollis Liverpool, interview by the author, Brooklyn, NY, 5 October 2014.

- 10 Frankie McIntosh, interview by the author, Brooklyn, NY, 24 October 2014.

- 11 Frankie McIntosh, interview by the author, Brooklyn, NY, 23 July 2013.

YouTube Links

- “Coming High” by Becket - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9gbG2eaHkl4

- “Wine Down Kingstown” by Becket - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dk-4lId73GU

- “Ash Wednesday Jail ” by Hollis “Chalk Dust” Liverpool - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AG2UP_RACXU