American Music Review

Vol. XLIV, No. 1, Fall 2014

By Paul Steinbeck, Washington University in St. Louis

George Lewis, 2004. Photo by Oskar Henn.

In his classic article “Improvised Music after 1950,” George E. Lewis writes: “the development of the improviser ... is regarded as encompassing not only the formation of individual musical personality but the harmonization of one’s musical personality with social environments, both actual and possible.”1 What Lewis’s assertion means, first of all, is that an improviser’s sense of identity takes shape within a social matrix, and that ensemble performance offers improvisers a space where the personal and the social can intersect, interact, and integrate. Furthermore, his term “musical personality” underscores the numerous ways in which improvisers use sound to cultivate their own identities and negotiate identity with their fellow performers. The implications of Lewis’s words are worth exploring at some length before I turn to this essay’s main topic: musical analysis.

Improvisers, especially those influenced by what Lewis describes as Afrological approaches to music-making, devote considerable time and effort to finding a crucial component of their identities: namely, their “personal sound[s].”2 This process starts with the first decision any would-be musician makes—choosing to play an instrument or become a vocalist—and continues for years, perhaps decades. Instrumentalists search for the perfect mouthpiece, reed, mute, string, stick, skin, cymbal, pickup, microphone, or amplifier, and some even become skilled at making their own instruments and accessories. What primarily determines an improviser’s personal sound, however, is not an instrument but the singular interface between one’s instrument and body. Practicing an instrument (or the voice, one’s internal instrument) will refine an improviser’s technique, but it also changes the body, and ultimately the two are inseparable. To become a musician is to inscribe upon oneself a personal history, an autobiography of one’s daily engagement with music that is audible in every performance, every note. As Lewis explains, “[n]otions of personhood are transmitted via sounds, and sounds become signs for deeper levels of meaning beyond pitches and intervals.”3

Of course, this narrative about sonic identity is not restricted to the musical experiences of improvisers. All musicians, improvisers or not, possess personal sounds defined by their instruments, bodies, techniques, and musical formations—although improvisers may place a higher value on attaining personal sounds that are especially unique and immediately identifiable. What, then, distinguishes an improviser’s sense of identity from that of a musician who does not improvise? To answer this question, it is necessary to examine the social context in which improvisation occurs. As I have already noted, Lewis characterizes “the development of the improviser” as involving “the harmonization of one’s musical personality with social environments, both actual and possible.”4 For Lewis, the operative concept is socialization: improvisers building their skills and forming their musical identities in dialogue with fellow musicians.5 For example, novice improvisers in pursuit of their personal sounds may begin by emulating a teacher or a well-known musician encountered through recordings. Then, during rehearsals and concerts, they can refine these personal sounds in real time as they “harmonize” their own identities with those of their co-performers. The same socialization process is at work when improvisers develop other aspects of their personal sounds: when they absorb the idioms of a particular musical style, when they internalize the performance practices of an ensemble, and when they discover how to contribute an unexpected musical idea at just the right moment in a performance—for improvisation thrives on what is “both actual and possible,” indeed on actualizing the impossible.

If a personal sound is at the very center of an improviser’s musical identity, then the other pillar of his/her identity is the ability to analyze. Now I am diverging from Lewis’s take on the matter. In “Improvised Music after 1950,” he portrays “analytic skill” as one piece of an improviser’s personal sound, but I prefer to regard a musician’s sound and analytical approach as two sides of the same coin, two complementary ways of conceptualizing improvisation.6 Of course, the real-time nature of improvisational performance makes it difficult to separate the sonic and analytical components of an improviser’s musical identity, but this is exactly the point. Sound and analysis are multifaceted, and both act upon each other in the course of performance. An improviser’s personal sound comprises tone, timbre, and technique; a body of knowledge about music and musicians; as well as the tendencies and possibilities that spontaneously emerge in performance when an improviser confronts the known and unknown, the somewhat anticipated and completely unanticipated. In other words, these sonic tendencies and possibilities are audible expressions of his/her thinking—which I might define, following the philosopher Gilbert Ryle, as “the engaging of partly trained wits in a partly fresh situation.”7 And, to return to the specific context of musical improvisation, what is thinking-in-performance but analysis?

Whether practiced by improvisers in real time or by music scholars in a stop-and-start fashion, analysis is founded on listening. Analysts hear, and then they think about what they hear, carefully deliberating on or mentally manipulating some of the sounds they perceive. Still more of what analysts hear is also processed, if not in a manner that leads to immediate reflection, and these sounds can inspire musical responses as well, just like the sounds to which they devote conscious attention. It is the nature of these responses that distinguishes the analytical work of improvisers. Scholars and other individuals listening analytically can react to the sounds they hear in many ways, from imagining other sounds to writing essays, but these responses inevitably stand outside the music. Improvisers’ analyses, in contrast, quickly return to the arena where they originate: the domain of musical sound. Analysis is always oriented toward action, and during improvisation the appropriate action is performance. The musicians’ sounding analyses become the music, prompting further analytical responses from their co-performers. To hear improvisation as analysis-performed—hundreds of successive and simultaneous cycles of listening, thinking, and acting—is to hear music like an improviser. The analytical strategies employed by improvisers rely heavily on perceptions and performances of identity. Certainly each improviser projects a unique analytical identity, a way of thinking-in-performance that is just as personal as his/her sonic identity. In ensemble settings, improvisers also attend closely to other musicians’ analytical approaches, intuiting their co-performers’ hearings and creative intentions as a way of refining their own analyses.8 Accordingly, the social matrix that influences improvisers’ personal sounds has an equally profound effect on how improvisers practice analysis. This point is illustrated in another of George E. Lewis’s writings, a retrospective of the time he spent as a guest performer with the Art Ensemble of Chicago. This took place in July 1977, during a weeklong gig at Storyville in New York.9 Lewis was substituting for the Art Ensemble trumpeter Lester Bowie, who spent the summer in Lagos, Nigeria, working with Fela Kuti.10 Lewis’s account focuses on how he attempted to bring his real-time analyses into alignment with the ways his co-performers were hearing the music:

As might be imagined, the Art Ensemble of Chicago is a very finely tuned and delicately balanced organism. Over the course of the five nights and fifteen sets at Storyville, I found that at certain times sound complexes arose in the shape of “calls” that seemed to arouse a collective expectation of the kind of contrasting ironic, ejaculatory brass witnessing that Bowie often employed. Already in such important Art Ensemble recordings as Live at Mandel Hall ... one clearly hears Bowie’s “commentary” as a kind of signifying punditry. As I discovered that the group members hadn’t quite adjusted to the gaps left by Bowie’s absence, I realized that part of my structural task would involve negotiating between exploring the dimensions of these lacunae and developing my own formal methodologies. This was not always successful at first. ... After one such set I kept the tape on as we moved from the stage to the dressing room; the recording captured Malachi Favors’ giving me a gentle dressing-down: “When we played that thing I thought you were going to do something”—that is, sonic signals were proffered that demanded the construction of a response.11

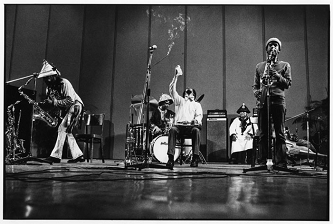

Art Ensemble of Chicago : Bergamo, 1974. Joseph Jarman (sax, left), Lester Bowie (trumpet), Roscoe Mitchell (sax, right), Malachi Favors (bass), Don Moy (drums). Photo by Roberto Masotti.

Lewis’s experience with the Art Ensemble provides a model for music scholars who analyze improvisation. First, scholars should prepare themselves through virtual rehearsals, listening closely and even playing along with recordings in order to gain familiarity with the repertoire and performance practices that they will encounter in analysis. Through this process, scholars can gain insight into the musicians’ knowledge bases and listening strategies: “what [they] know, hear and imagine, and share.”12 Additionally, music scholars must consciously identify with the individual performers while analyzing, as Lewis did while taking Bowie’s place in the Art Ensemble. Of course, Lewis did not abandon his own musical identity at Storyville—an impossibility, at any rate. He instead tried to hear the “calls” and “gaps” in the music as Bowie would have, adjusting his listening approach by adopting certain aspects of Bowie’s analytical identity. Lewis also learned to project Bowie’s sonic identity during crucial moments in the performance, thereby fulfilling what the members of the Art Ensemble expected from Bowie’s replacement. Although Bowie was some five thousand miles away in Lagos, his composite musical identity was very much present on the Storyville stage.

An analytical method that emulates improvisation would require that music scholars cultivate a deep sense of “personal involvement” with performance.13 Marion A. Guck observes, in her influential article “Analytical Fictions,” that written musical analyses “typically—necessarily—tell stories of the analyst’s involvement with the work she or he analyzes,” but what I am now envisioning differs from Guck’s idea in one crucial respect.14 In the case of improvisation, analysts properly involve themselves with the performers, identifying with the music’s co-creators rather than what is created. When analyzing improvisation, scholars must enter into what improvisers experience: music, created in real time, emergent from the performers’ personal sounds and sounding analyses, and continuously shaped by social relations.

Real-time creation, emergence, and sociability: does this scenario describe only improvisation? Or is it also applicable to other musical practices, such as performing composed music? The philosopher Bruce Ellis Benson argues that all musical practices are “essentially improvisational in nature, even though improvisation takes many different forms in each activity.”15 Benson asks scholars to experience music as improvisational, as a space where composers, performers, and even listeners participate in dialogue and co-creation.16 Benson’s aesthetic position is closely related to a theory developed by Nicholas Cook. In his book Beyond the Score, Cook (re)frames music as performance, drawing on interdisciplinary performance theory as well as the familiar philosophical distinction between process and product. By focusing on performance, Cook is able to move beyond “literary” conceptions of “music as writing,” thereby opening up new analytical perspectives on music making.17 According to Cook, musical meaning is fundamentally social—created between performers and other experiencers—and it matters not whether the performers are working from a through-composed score, engaging in free improvisation, or doing anything else. However, Cook does not ask music scholars to simply erase the conceptual categories of “composition” and “improvisation,” as some have lately been tempted to do.18 In contrast, he urges scholars to consider the connections between musical structures and social structures, between the particular features of a musical practice or piece and the social interactions that emerge in performance.

With Cook’s performance theory, I have returned to where this essay began. Improvisation is a social practice, as is performance. Because both phenomena are social in nature, any understanding of improvisation (and performance in general) must be informed by the study of musical identity. Indeed, without a certain grasp of the sonic and analytical identities that musicians bring to the space of performance, scholars cannot productively analyze any form of real-time music making.

This means that ethnography is indispensable to musical analysis. Listening exercises and virtual rehearsals will provide some insight into how sonic and analytical identities operate during performance, but if scholars complement these approaches with ethnographic findings, they can create more accurate portrayals of musicians’ actions and interactions. Furthermore, collaborative ethnography with performers and other participants allows scholars to incorporate multiple perspectives into their analyses, moving closer to an ethical practice of analysis. These conclusions about the utility—and necessity—of ethnography bring to mind Nicholas Cook’s declaration to his fellow music scholars that “we are all ethnomusicologists now.”19 To those who are familiar with the inner workings of most American music departments, Cook’s assertion may seem premature. But it is nonetheless clear that musicologists and theorists must become ethnographers, if they want to fully comprehend improvisation, performance, and real-time musical experience.

Notes

- 1 George E. Lewis, “Improvised Music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives,” Black Music Research Journal 16/1 (Spring 1996), 110–111.

- 2 Ibid., 117.

- 3 Ibid.

- 4 Lewis, “Improvised Music after 1950,” 110–111.

- 5 For more on the socialization of improvisers, see Edward T. Hall, “Improvisation as an Acquired, Multilevel Process,” Ethnomusicology 36/2 (Spring-Summer 1992), 225–7.

- 6 Lewis, “Improvised Music after 1950,” 117.

- 7 Gilbert Ryle, On Thinking, ed. Konstantin Kolenda (Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1979), 129.

- 8 For a formal model of how improvisers assess each other’s intentions, see Clément Cannone and Nicolas Garnier, “A Model for Collective Free Improvisation,” in Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Mathematics and Computation in Music, ed. Carlos Agon et al. (Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2011), 32–40.

- 9 George E. Lewis, “Singing Omar’s Song: A (Re)construction of Great Black Music,” Lenox Avenue 4 (1998), 74.

- 10 Paul Steinbeck, “‘Area by Area the Machine Unfolds’: The Improvisational Performance Practice of the Art Ensemble of Chicago,” Journal of the Society for American Music 2/3 (August 2008), 406.

- 11 Lewis, “Singing Omar’s Song,” 76. The recording mentioned by Lewis is Art Ensemble of Chicago, Live at Mandel Hall, Delmark DS 432/433, 1974, LP.

- 12 George E. Lewis, “Critical Responses to ‘Improvisation: Object of Study and Critical Paradigm,’” Music Theory Online 19/2 (June 2013), [17].

- 13 Marion A. Guck, “Analytical Fictions,” Music Theory Spectrum 16/2 (Fall 1994), 218.

- 14 Ibid.

- 15 Bruce Ellis Benson, The Improvisation of Musical Dialogue: A Phenomenology of Music (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 2.

- 16 Ibid., 126.

- 17 Nicholas Cook, Beyond the Score: Music as Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 1.

- 18 Bruno Nettl, “Contemplating the Concept of Improvisation and Its History in Scholarship,” Music Theory Online 19/2 (June 2013).

- 19 Nicholas Cook, “We Are All Ethnomusicologists Now,” in Musicology and Globalization: Proceedings of the International Congress in Shizuoka 2002, ed. Yoshio Tozawa and Nihon Ongaku Gakkai (Tokyo: Musicological Society of Japan, 2004), 52–55.