American Music Review

Vol. XLV, No. 2, Spring 2016

By Edward A. Berlin

Ragtime composition today can be divided into two broad categories: rags that adhere to the piano style of the original period, extending from the late 1890s through World War I, and those that retain the spirit and some of the elements of the original style, but express it with a more current musical language. Composers of the first category include many ragtime fans, amateur perform ers, and a few professionals. In imitating this historic music style, they adopt the well-defined conventio ns of ragtime: two sixteen-measure strains in the tonic followed by a “trio” of one or two strains in the subdominant, all characterized by tonal harmonies and melodies and a few stereotyped syncopation patterns. Modeled on the best rags, many of these compositions are quite good as measured against the general ragtime output of the original period, but they remain old rags recently written.

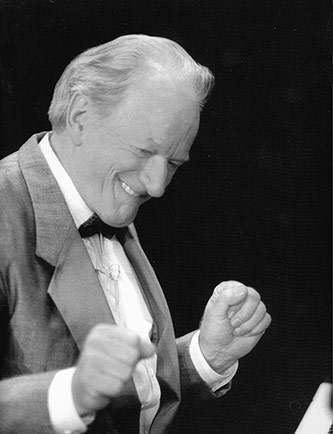

Proponents of the other category include composers established in different genres who use their skills and experience to create a ragtime that could not have existed in the earlier period. Max Morath straddles the two categories, but leans heavily toward the modernist camp. Though he has composed for many years, he is not a full-time composer; his works have been incidental to his theatrical performances that use popular music to reveal an historical Americana, with some emphasis on the ragtime years. His seventeen rags, spanning five decades beginning in 1954, reflect several styles. Not surprisingly, his earliest—the irrepressible Imperial Rag (1954)—assumes the manner of an historical rag, though it includes features not common at that time, such as an opening on a diminished seventh chord and triplet passages suggestive of the novelty piano style of the 1920s.

As he developed his individual ragtime style, he extended the defining trait of ragtime—its restless syncopation—with other disruptive or unsettling rhythmic devices. These are mainly (1) duple and triple meter shifts, and (2) polyrhythms, with one hand playing in three against a duple in the other. Instances of meter shifts can be found in such works as Golden Hours (1972) and One for Amelia (1964). Polyrhythms are included in such rags as Polyragmic (1964), One for Norma (1975), and One for the Road (1983). Morath further expands his concept of unsettling rhythms further by lengthening or shortening phrases and strains; instead of the anticipated four-measure phrases and sixteen-measure strains, he may present phrases of three or five measures, strains of nine, thirteen, or twenty mea sures. It all throws us off stride and keeps us paying attention. Morath’s harmonic language also evolved as his style developed, becoming less conventional and more complex. In Anchoria Leland (1981), a piece especially rich in surprises, he has touches of polytonality.

Morath’s natural inclination toward drama might have prompted the programmatic effects he uses in Echoes of the Rosebud (1975). The title refers to Tom Turpin’s Rosebud Bar, an early twentieth-century center for ragtime piano-playing in St. Louis. We hear familiar melodies—a little bit of Charles Hunter, some Scott Joplin—but they are not quite right: the rhythms and other elements are somewhat askew, suggesting a misty, imperfect recall, echoes in which certain details have been lost or distorted.

All seventeen rags are treated to sparkling, robust performances by Aaron Robinson on an MAI CD. Robinson’s departures from the score, mostly slight embellishments, strike this listener as spontaneous and enthusiastic responses to the music. Sample clips can be heard on the Amazon page offering individual tracks and the complete CD, and on http://www.cdbaby.com/cd/aaronrobinson8. The scores are available in the folio Max Morath, Original Rags for Piano, published by Hal Leonard (http://www.halleonard.com/). These fascinating rags are worth examining and performing.