American Music Review

Vol. XLII, No. 2, Spring 2013

By Tom Zlabinger, York College

Every year since 2008, my students and I have had the honor to be invited by Patricia Parker to perform with other student ensembles as part of the international Vision Festival in New York, which she produces every summer. The Vision Festival is rooted in the music of Albert Ayler, Cecil Taylor, John Coltrane, and others whose music developed into the loft scene in New York during the 1970s. To connect this music with younger audiences and feature younger improvising ensembles from around New York City, Parker has presented a Saturday afternoon performance every year that showcases educators and their ensembles. Because of these experiences, my outlook on the teaching of improvised music has shifted from a widely-accepted model to one based in free improvisation. I offer here my personal story on how my thinking about improvisation and education has changed.

The York College Creative Ensemble at Vision Festival 17 (2012)

After moving to New York City in 2000, and taking a teaching position at York College in 2003, I evolved from student of jazz to educator. In the beginning my approach to teaching was very traditional: learn the repertoire, analyze chord structure, and apply the appropriate chord scales. In addition to transcription and listening to both recordings and live performances, this was how the process of learning to improvise had been modeled for me by my own teachers. Yet after the initial excitement of working with students and sharing my knowledge, I became frustrated with the method. Though I found it hard to articulate at the time, what had originally seemed to be a process of illuminating possibilities and exploring options had transformed into the enforcing of sonic dogma.

On 13 April 2007, the club Tonic on Manhattan’s Lower East Side was forced to close (now one of many to do so in recent years), a result of real estate development in the area and the rising cost of rent. Since the venue opened in 1998, Tonic showcased music nightly that represented more adventurous improvised music. Over the years, I had seen many of my most favorite shows at Tonic and attended the final official performance at the venue, hosted by John Zorn and featuring many famous downtown improvisers. The following Saturday morning, I attended a protest of the club’s closing and with many others occupied the building illegally. Musicians associated with the venue including cornetist and composer Lawrence D. “Butch” Morris, pianist Matthew Shipp, guitarist Marc Ribot, wind player Ned Rothenberg, and others gave impromptu performances while people outside carried signs that read “Save Our Music,” “NYC in Cultural Crisis,” and “Condos ≠ Culture.” By early afternoon, the police arrived and asked us to vacate the premises. In an act of civil disobedience, Marc Ribot refused to leave the stage and continued performing the classic labor song “Bread and Roses” until he was arrested and taken away in handcuffs. The arrest was reported in several newspapers and blogs. Most importantly a discussion about the changing creative music landscape began around the shuttering of Tonic, which, sadly, remains closed and unoccupied six years later.

As powerful as it was to see a musician I admired protest the changing cultural landscape, it was the performances that morning which changed my mind and heart most. Though I did not participate myself as a musician, I witnessed many different groupings of artists come together and instantly make music. Until that moment, I had wrongly assumed that making freely improvised music of consequence was only arrived at through chemistry between musicians who had been working together for extended periods of time. Granted, the strongest improvisations come from those who have been improvising the longest and have established a relationship with other improvisers. But a new picture was painted for me as unestablished groups of people performed together. Most impressive was a conduction by Butch Morris. Using a set of hand gestures that were explained at the time to represent certain instructions (long tones, repetition, dynamics, and development), he created a mesmerizing performance with only his baton and the musicians who just happened to be there that day.

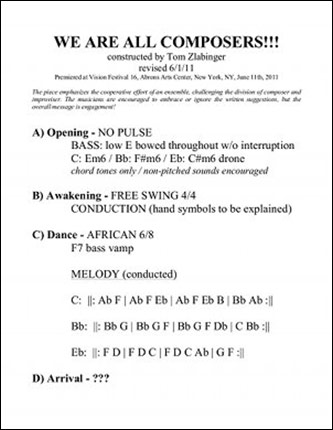

Score for WE ARE ALL COMPOSERS!!! by Tom Zlabinger

It was at Tonic’s closing that I first met Patricia Parker. She and others organized a press conference at City Hall the following Tuesday where many downtown musicians spoke to the press. (These speeches and other footage surrounding the closing of Tonic are easily found on YouTube). As a result of these events, Patricia Parker founded an organization called Rise Up Creative Musicians and Artists (RUCMA). The group began to have meetings about everything from arts advocacy to artist housing to PR campaigns and, most important here, education. The following year performances by student ensembles began at the Vision Festival.

Largely because of the experience of that Saturday morning in April, I have over the past six years aligned myself with the extended downtown community and performed mostly free music professionally with some of the most important artists in the genre, including Marshall Allen, Roy Campbell, Daniel Carter, Jason Kao Hwang, Matt Lavelle, Sabir Mateen, Butch Morris, Ras Moshe, and William Parker. The experience served as the apprenticeship that I did not have through traditional education.

I returned to the classroom that spring feeling pulled in two directions. I would perform freely improvised music in the evenings, but would ask my students to apply certain scales to certain chord progressions in rehearsal. I was still convinced that one must learn jazz basics before moving to freely improvised music. The process takes time and cannot be rushed. Then I began participating with my students in the Vision Festival and my pedagogical approach slowly began to change.

I conduct two big bands at York College: the York College Big Band and the high school-level York College Blue Notes. For the first three years at the Vision Festival, I brought the younger group. The first two years we performed music composed by Charles Mingus as the music seemed most appropriate for the festival. But after the second year, Patricia Parker mentioned that I did not give my students enough freedom. At the time I was very offended. The students had worked hard on the music of Mingus and performed it in the unconventional and often chaotic tradition of this great musician and composer. But the anger was short-lived.

In 2009, an alumnus of the high school ensemble who became a student at the college passed away tragically at the age of nineteen. In his memory, I constructed a performance entitled Without Answer: a Requiem for Shamar Olivas (1990 – 2009) for Soloist, Big Band, and Decision Maker, which the York College Blue Notes premiered with Roy Campbell as a guest soloist. The piece was a multi-movement work compiled from a set of written-out options and suggestions. In each of the five movements (Before / With / Without / Answer / Acceptance), various members of the ensemble (saxes, brass, bass, drums), or soloists or combinations thereof were given a sequence of simple instructions (punches, riffs, freeze sound, silence, and others) written on paper. Every member received the same sheet so he or she knew what the entire ensemble was performing at all times. The instructions were mostly suggestions and musicians could choose harmonic content, granted they continued to listen and contribute to the larger sound of the ensemble at that moment. But some instructions were more specific (for example, D vamp, E-flat drone, or 6/8 groove). At one point, all horns and soloist were instructed to play a sequence of five notes that were repeated and cued rhythmically by me the “decision maker” known as “Boogie’s Theme.” (“Boogie” was Shamar’s nickname.) Shamar’s parents attended the deeply-moving performance. This would be the beginning of a pedagogical shift in my teaching. In composing a piece in honor of Shamar, I had also created a construction and performance that healed wounds for both me and the audience.

I brought the college ensemble to the Vision Festival the following year, and constructed another multi-movement piece for large ensemble entitled WE ARE ALL COMPOSERS!!!, emphasizing the co-compositional aspect of group improvisation. Although the high school ensemble was successful with their performance the previous year, there was something different about the experience with this construction and its performance by the older ensemble. I had previously believed that one must slowly progress to free and more adventurous improvisation. These slightly older students had a confidence that translated into even more powerful results. Whereas I felt the younger students needed encouragement to freely improvise, the slightly older students were eager to break down barriers. And this is where a key concept arises: ownership of improvisation. I suggest that as older musicians they have a greater wealth of performance experience and listening history that could be applied to making decisions in a freer performance. As a result, these students felt the music performed was “theirs,” because they constructed it together in the moment in contrast to a performance that was based more on written-out music of a more traditional big band.

Shortly after the 2011 performance, I began experimenting with a satellite ensemble of the older big band originally called The Beyond... Band. The group was not restricted to big band instrumentation, as it did not always require the traditional five saxes, four trumpets, four trombones, and rhythm section lineup. The group usually maintains the horns plus rhythm section architecture, but has also included non-traditional big band elements like soprano saxophone, tabla, and a second set drummer. The ensemble performed at a few gallery openings on our campus. Sometimes I would do conductions. Sometimes I would just play bass or trombone in the band. In February 2012, Patricia Parker invited us to participate in a performance with other college ensembles from the New School (directed by Reggie Workman) and Brooklyn College (directed by Salim Washington) and I decided to change the name of the group to reflect the occasion. The York College Creative Ensemble was born. Since the performance was the day before Valentine’s Day, we based our performance on John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme riff. Later that spring, the ensemble gave a presentation as part of the college’s annual Student Research Day entitled “What is the York College Creative Ensemble?” Students and faculty were allowed to ask questions about what the ensemble was doing and how it contrasted with the big band. The members of the ensemble were eager to talk about the freedom to more accurately express their emotions. Since the Creative Ensemble’s beginning, students have been eager to be involved. For the last two years, the group has been enthusiastically received at the CUNY Jazz Festival at City College.

The success of the Creative Ensemble surprises me. I hope to conduct more formal interviews with my students about their experiences and observations. But in the meantime, I know from casual conversations they love the immediacy and challenge of freely improvised music. This spring I taught a Jazz Improvisation class and though I discussed traditional jazz practices, I found my students leaned more and more to the freely improvised music. Our final concert included more free improvisation than traditional standards. And some standards were deconstructed and treated more as departure points. Students were engaged in the decision making process of building ensembles and discussing strategies on how to improvise. One student even included a freely improvised piece as an encore to his senior recital.

York College Creative Ensemble perform at the Vision Festival 17 - Part 1

Clearly, my students greatly benefit from the process of free improvisation when taught at a certain point in their development. Two students in the Jazz Improvisation class who resisted the free playing initially thanked me profusely at the end of the semester, claiming they could hear better as a result of looking for moments of creation and opportunity. The process of playing freely made them feel like stronger musicians in general and also sharpened their ears when playing more traditional music.

On 11 May 2013, I was invited by the Music Educators Association of New York City (MEANYC) to present the workshop “Beginning Improv...Have No Fear!” at the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) headquarters in Manhattan. I based the workshop on my ideas about teaching improvisation to a group of educators (most of whom were classical musicians). We began with free improvisation and concluded with a conduction. While we talked, I even suggested that I had recently changed my approach and would have previously given them exercises to rehearse blues scales and thus overloaded them with information. The improvisations improved during the short time we had together. As educators, they began to see the advantages of free improvisation and how a culture of ownership could begin to build a foundation to develop improvisers.

York College Creative Ensemble perform at the Vision Festival 17 - Part 2

After all these experiences, I now firmly believe that young musicians should be asked to improvise freely more often and over time build their own vocabulary and phrasing, much like language acquisition. I appreciate my long evolution to this point in my teaching career, and delight in sharing it with others. The earliest musicians improvised long before music was notated. And we cannot forget that great composers like Bach, Mozart, and many others improvised. As music educators, we should do more to follow this trajectory in musical evolution. We owe our students the time to hold the music completely in their own hands and ears. Making spontaneous music primarily through intuition can be profoundly rewarding and contribute to a deeper understanding of the art to which many of us have devoted our lives.