American Music Review

Vol. XLII, No. 2, Spring 2013

By Yoko Suzuki, University of Pittsburgh

The story of alto saxophonist Vi Redd illustrates yet another way in which women jazz instrumentalists have been excluded from the dominant discourse on jazz history. Although she performed with such jazz greats as Count Basie, Max Roach, Dizzy Gillespie, and Earl Hines, she is rarely discussed in jazz history books except for those focusing specifically on female jazz musicians. One reason for her omission is that jazz historiography has heavily relied on commercially produced recordings. Despite her active and successful career in the 1960s, Redd released only two recordings as a bandleader, in 1962 and 1964. Reviews of these recordings, along with published accounts of her live performances and memories of her fellow musicians illuminate how Redd's career as a jazz instrumentalist was greatly shaped by the established gender norms of the jazz world.

allaboutjazz.com">

allaboutjazz.com">

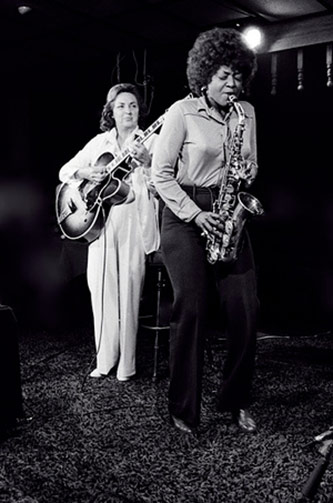

Vi Redd (saxophone) and Mary Osborne (guitar) June 1977, Photo courtesy of allaboutjazz.com

Elvira "Vi" Redd was born in Los Angeles in 1928. Her father, New Orleans drummer Alton Redd, worked with such jazz greats as Kid Ory, Dexter Gordon, and Wardell Gray. Redd began singing in church when she was five, and started on alto saxophone around the age of twelve, when her great aunt gave her a horn and taught her how to play. Around 1948 she formed a band with her first husband, trumpeter Nathaniel Meeks. She played the saxophone and sang, and began performing professionally. She had her first son when she was in her late twenties, and a second son with her second husband, drummer Richie Goldberg, a few years later. It was in the 1960s that Redd's popularity as a jazz saxophonist/singer peaked.

The Los Angeles Sentinel's coverage of her musical career starts in August 1961, when she had a weekly gig with Goldberg and an organ player at the Red Carpet jazz club. In the same year, Redd appeared at the club Shelly's Manne-Hole. In 1962 she performed at the Las Vegas Jazz Festival with her own group. The Los Angeles Sentinel reported, "Another first for the Las Vegas Festival on July 7 and 8 is achieved when Vi Redd, an attractive young girl alto sax player, becomes the first femme to be one of the instrumental headliners at a jazz festival. As a matter of fact, Miss Redd, may well be the first gal horn player in jazz history to establish herself as a major soloist."1 Here, Redd, a 34-year-old woman with two young children, is described as an "attractive young girl." Moreover, as is often the case with any male dominated field, being the "first" female is emphasized. A few months later the Sentinel wrote, "Vi Redd, first woman instrumentalist in participating in the recent Las Vegas Jazz Festival is jumping with joy as she was placed 5th in the Down Beat critics poll," confirming her status in the jazz scene.2

In 1964 Redd toured with Earl Hines in the U.S. and Canada, including engagements in Chicago and New York. The Chicago Defender reported on their appearance at the Sutherland Room: "Featured with ‘Fatha' Hines in his showcase are Vi Redd, a sultry singer who also plays the saxophone as well or better than many male musicians."3 In 1966, she played at the Monterey Jazz Festival with her own band, and the next year she traveled to London by herself to play with local musicians at the historic Ronnie Scott's jazz club. She was initially invited there as a singer and was scheduled to perform for only two weeks, but due to popular demand her performance was extended to ten weeks. Typically, Ronnie Scott's featured an instrumental group with a lesser-known vocalist as an opening act. Bassist Dave Holland, who played with Redd, recalled that she both played and sang and was enthusiastically accepted by the London audience. Prominent jazz critic Leonard Feather, a prominent white male jazz critic/producer, wrote "Booked in there (Ronnie Scott's)...only as a supporting attraction...she often earn[ed] greater attention and applause than several world famous saxophonists who appeared during that time playing the alternate sets."4 Jazz critic/photographer Valerie Wilmer echoed that sentiment in Down Beat, noting that Redd "came to London unheralded, an unknown quantity, and left behind a reputation for swinging that latecomers will find hard to live up to."5 Redd's London appearance was clearly extremely successful.

The summer of 1968 was another high point in Redd's music life. She made a guest appearance with the Dizzy Gillespie Quintet at the Newport Jazz Festival in early July. This performance caught the eye of writers and critics who attended the Festival, including photographer/writer Burt Goldblatt:

HITCHQUOTE At one point he (Gillespie) introduced female sax player Vi Redd as "a young lady who has been enjoyed many times before..." Later while she warmed up with pianist Mike Longo, Dizzy interjected, "That's close enough to jazz," convulsing the audience once again. But despite all the male-chauvinist-inspired humor she encountered, Vi fluffed it off and played a fine, Bird-inspired solo on "Lover Man."6

In the accompanying photograph, Redd was wearing a very short dress, fishnet stockings, and high heels. Pianist Mike Longo remembered the concert very well. According to him, Redd sat in with Gillespie's band on many occasions whenever they toured California. "She always sounded good and she was very cool as a musician and a person."7 More interestingly, he denied Gillespie's chauvinistic attitude mentioned in Goldblatt's history of the Newport Festival book. "That was a routine joke Dizzy made every night. Vi was tuning up with me and Dizzy said that's close enough for jazz, meaning it doesn't have to be as accurate as Western classical music. Dizzy was one of the very few people who hired female musicians like Melba Liston. He had so much respect for Vi."8

Two renowned jazz critics, Stanley Dance and Dan Morgenstern, also reported on this performance in Jazz Journal in the UK and Down Beat in the US respectively. Dance wrote, "[Gillespie] provoked loud guffaws from the crowd by introducing ‘a young lady who has been enjoyed many times before.' Vi Redd seemed to take this gallantry in her stride ..."9 Despite Longo's statement, Gillespie's introduction of Redd and the audience's reaction do suggest a chauvinistic atmosphere. Dance's description of Redd's saxophone performance is neutral, mentioning only that she is "Bird-influenced." Morgenstern, on the other hand, called Redd a "guest star" and states, "Miss Redd sings most pleasantly...and plays excellent, Parker-inspired alto. To say she plays well for a woman would be patronizing—she'd get a lot of cats in trouble."10 Certainly, that Redd was a female saxophonist wearing feminine clothing evoked male-female tensions on the stage in these writers' minds. However, as suggested in Longo's statement, some open-minded musicians actually did not care that Redd was a female saxophonist, and did not let it affect their professionalism.

Later in the summer of 1968, Redd traveled to Europe and Africa with the Count Basie Orchestra as a singer. She performed publicly at several prestigious clubs and jazz festivals, attracting writers' attention and eliciting passionate reaction from audiences, especially in Europe during the late 1960s.

Around 1970, she started to perform less in order to stay home with her children and teach at a special education school. About five years later, at the age of forty-seven, she gradually resumed her performing career. In 1977 Redd was appointed as a Consultant Panelist to the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities in Washington, DC. For the past thirty years she has been working as a musician and educator, giving concerts, touring abroad, and lecturing at colleges. In 2001, she received the Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Award.

Regardless of her exposure at public concerts during the 1960s, she did not have many opportunities to be recorded. In his 1962 Down Beat article, Leonard Feather offered an anecdote revealing how difficult it was for female jazz instrumentalists to get recorded. "Redd sat in with Art Blakey, who promptly called New York to rave about her to a recording executive. The record man's reaction was predictable: ‘Yes, but she's a girl...only two girls in jazz have ever really made it, Mary Lou Williams and Shirley Scott...I wonder whether to take a chance....'"11 This story demonstrates that female jazz instrumentalists, with the exception of a few keyboardists, did not fit into the dominant gender ideology of the period's jazz recording industry.

Redd's two recordings as a leader were produced by Feather, who discovered Redd through the recommendation of drummer Dave Bailey. Bailey explained, "I met Vi probably at a jam session in LA around 1962. Everyone told me that she sounded like Bird. When I heard her play, I was blown away. I thought she deserved attention, so I mentioned her to Leonard."12 After his experience at the Red Carpet, Feather helped Redd sign with United Artists, produced her two records, and wrote glowingly about her for Down Beat. He also paved the way for her to perform at Ronnie Scott's as well as booking her for the Beverly Hills Jazz Festival in 1967.

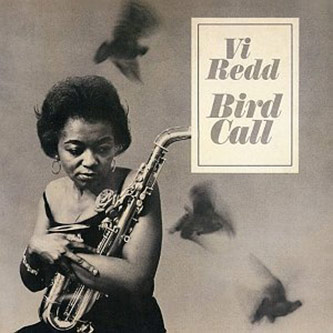

Vi Redd's first album Bird Call (1962)

On her first album, Bird Call (United Artists, 1962), Redd recorded ten tunes: five were instrumentals, one was a vocal, and she both sang and played on four others. When she was asked if she "had control over what [she] wanted to play" on the record, she answered that Feather had the idea of recording Charlie Parker related tunes.13 Her second album, Lady Soul, was released in 1963. On this record, Redd sang on the majority of tracks; out of eleven tracks, three were vocal tunes, two instrumental, and six combined vocals and saxophone. Even on these six tunes, her saxophone solos were limited. Interestingly, four tunes were blues. Jazz critic John Tynan reviewed Lady Soulin Down Beat's "column of vocal album reviews" and wrote, "A discovery of Leonard Feather, Vi Redd may be more celebrated in some quarters as a better-than-average jazz alto saxophonist than as a vocalist. In Lady Soul Miss Redd the singer dominates on all tracks excepting two instrumentals, ‘Lady Soul,' a deep-digging blues, and the ballad ‘That's All'."14 Dave Bailey, who played drums on this recording, recalled, "I think Ertegun, the owner of Atlantic, selected the tunes we recorded. I think they were trying to get her more recognized as a singer."15 Leonard Feather confirmed in his liner notes for Lady Soul that Nesuhi Ertegun had suggested the inclusion of "Salty Papa Blues" and "Evil Gal's Daughter Blues," both written by Feather and his wife. The change from the more instrumental album to a more vocal and bluesy approach hints at their effort to follow traditional gender categories in the recording industry. In fact, Redd herself did not like the second album, only mentioning that "it wasn't the right thing to do."16

As a sidewoman, Redd participated in several important recordings. For example, she performs on two songs, "Put It on Mellow" and "Dinah," on trombonist Al Grey's Shades of Grey (1965), with a large ensemble of musicians featuring many members of the Count Basie Orchestra. Sally Placksin wrote that Redd considered these two instrumental songs to be her best recorded performances.17 "Put It on Mellow" is a slow ballad, in which Redd demonstrates her saxophone's "raw, gutty quality,"18 for which she was frequently praised. Her rendition of "Dinah" showcases Redd's ability as a well-rounded jazz instrumentalist. Though this old popular song is often played in a medium to up tempo, on this recording "Dinah" is a ballad that features Redd's alto saxophone. Backed by a richly textured harmony of tenor sax, trumpet, and three trombones, Redd beautifully embellishes the melodies with her distinctively resonant and silky sound. After the first chorus, she improvises on the bridge section over the rhythm section's double time feel. Toward the end, Redd creates an emotional and climactic moment with a fast ascending phrase and a repeated two-note figure in the high register, demonstrating her technical mastery and expressiveness.

In 1969, she joined the recording session of multiinstrumentalist Johnny Almond's jazz-rock album, Hollywood Blues, playing alto sax on two tunes. Her last recording was on Marian McPartland's Now's the Time, which was recorded immediately after Redd resumed her performing career. McPartland organized an "all-female band" for a jazz festival in Rochester, New York. On this live recording album, Redd played alto sax on several songs.

Redd's singing can be heard on three CDs: The Chase! by Dexter Gordon and Gene Ammons, Live in Antibes, 1968 and Swingin' Machine: Live by the Count Basie Orchestra. The Chase! is a live album recorded in 1970 (reissued as a CD in 1996) on which Redd sings "Lonesome Lover Blues." Count Basie's Live in Antibes was recorded when Redd toured Europe with the Count Basie Orchestra in 1968. The first two tunes display her excellence as a blues singer: resonant and husky voice, shouting, bending, and twisting notes, melismatic singing, story telling, call and response with the band, and the delivery of bluesy feeling. The last song, "Stormy Monday Blues," however, stands out because she also plays a two chorus saxophone solo.19 She skillfully improvises using both bebop and blues inspired melodies.

One wonders why Redd had more opportunities to perform in public than to record. It is possible that musicians recognized her excellence as a saxophonist and invited her to sit in with them. Who gets recorded, however, is not necessarily determined by recognition and reputation among musicians. In the end, Redd's two recordings as a leader were made with the help of Feather. Strangely, she did not have the chance to record as a leader at the peak of her career in the late 1960s. Moreover, most of her recordings went out of print and became collector's items.20 Both recording opportunities and reissues reflect traditional gender norms in the recording industry. Redd has been obscured and forgotten precisely because she did not have those opportunities.

In an extensive interview with Monk Rowe of the Hamilton College Jazz Archives, Redd explained how she joined the Count Basie Orchestra: "They needed somebody that could sing the blues, and I mostly sang rather than played, those guys had some problems with me playing."21 Further reflecting on her experience with the Basie Orchestra, she said, "He [Basie] didn't let me play [alto saxophone] much because Marshal [Royal, the lead alto player for the Basie band] didn't like it. When I was singing, they were happy, but as soon as I started playing, they didn't like that."22 Clearly she was accepted more as a singer than as a saxophonist.

Feather stated "she [Redd] has too much talent. Is she a soul-blues-jazz singer who doubles on alto saxophone? Or is she a Charlie Parker-inspired saxophonist who also happens to sing?"23 There are mixed views on whether her main instrument was saxophone or voice. When pianist Stanley Cowell recalled Redd performing in London, his impression was that Redd only sang. This is possibly because he thinks that she was a better singer than a saxophonist. Cowell lived in Los Angeles from 1963 to 1964, where he saw Redd performing at local jazz clubs. He suggested, "She was a good saxophonist. But too many great saxophon- ists were around. And she could really sing."24 On the other hand, Mike Longo stated, "I didn't know she was a singer. I always thought she was a saxophon- ist because she always came to sit in with us and only played saxophone."25 It is difficult to imagine that Redd never sang with Gillespie's band until the Newport Jazz Festival. Longo continued, "You know, gender doesn't matter to music. It doesn't matter who plays."26 Perhaps Longo's gender-neutral attitude led him to recognize Redd as a jazz instrumentalist more than others.

Dave Bailey recently recalled, "She could have made it either way. She could play as good as the guys. And she was an awesome singer."27 He compares her to men only when he describes her saxophone performance, suggesting the saxophone's specific association with male performance. Bailey does not hesitate to say that "women don't associate themselves with the instruments."28 Although Redd was raised in an exceptional environment—family members, neighbors, and classmates were established musicians — even her father was unwilling at first to hire her in his band. Redd said, "I guess he had his chauvinist thing going, too."29

Cowell also recalled that Redd played very strongly "like a man, and that was what I liked about her."30 Although Redd demonstrates sensitivity and elegance in her beautiful ballad playing, it is her strength and gutsy blues feeling that seem to be most appreciated as a talented saxophonist. Cowell continued, "She was tough, soulful, and culturally black. She could curse you out, cut you down with her words."31 His description fits a stereotypical image of black womanhood, particularly a blues performers. As Patricia Hill Collins contends, blues provided black women with safe space where their voices could be heard, and in the classic blues era, more women than men were recorded as singers in the idiom.32 Redd's strong connection with the blues, however, was sometimes taken negatively among musicians. Cowell stated, "Some young musicians weren't willing to work with Vi, because they thought her music was not progressive enough."33 Cowell also thought that Redd did not develop her musical style adequately and remained within the comfortable realm of the blues. Indeed, the blues might have remained her comfort zone not only musically but also culturally and socially.

In addition to black women's association with the blues, the stereotypical dichotomy "men are instrumentalists, women are singers" continued to persist throughout the jazz world of the 1960s and 1970s. Because of these cultural constructions, Redd was perceived as a vocalist more than a jazz saxophonist, despite her considerable talents and contributions as an instrumentalist. Vi Redd's career path exemplifies how the music of female jazz instrumentalists remains largely invisible to jazz history.

Notes

- 1 "Vi Redd Headlines Jazz Bash," Los Angeles Sentinel, 28 June 1962, C1.

- 2 "Gertrude Gipson...Candid Comments," Los Angeles Sentinel, 9 August 1962, A18.

- 3 "Last Chance to See ‘Fatha,'" The Chicago Defender, 29 August 1964, 10.

- 4 Leonard Feather, liner notes for Vi Redd, Bird Call (1969 Reissue, Solid State 3518038).

- 5 Valerie Wilmer, "Caught in the Act," Down Beat Vol. 34, No. 4 (1968), 34-35.

- 6 Burt Goldblatt, Newport Jazz Festival: The Illustrated History (New York: The Dial Press, 1977), 154.

- 7 Mike Longo, personal communication with author (6 May 2005).

- 8 Ibid.

- 9 Stanley Dance, "Lightly & Politely: Newport, '68," Jazz Journal, Vol. 21, No. 9 (1968), 4.

- 10 Dan Morgenstern, "Newport Roundup," Down Beat Vol. 35, No. 18 (1968), 34.

- 11 Leonard Feather, "Focus on Vi Redd," Down Beat Vol. 29, No. 24 (1962), 23.

- 12 Dave Bailey, personal communication with author (1 June 2005).

- 13 Vi Redd, interview with Monk Rowe (13 February 1999).

- 14 John Tynan, "Vi Redd-Lady Soul," Down Beat, 31/4 (1964), 33.

- 15 Bailey, 2005.

- 16 Vi Redd, personal communication with author (5 September 2009).

- 17 Leonard Feather, liner notes for Lady Soul (Atco 33-157, 1963).

- 18 Sally Placksin, American Women in Jazz: 1900 to the Present (New York: Wideview Books, 1982), 259.

- 19 Redd is credited only as a singer in the liner notes. Therefore, people who are unfamiliar with Redd's playing may not realize she played the saxophone solo.

- 20 Her two recordings as a leader have gone out of print. The first album was reissued by Solid State (a division of United Artists) in the late 1960s. One tune from the second album was included on a compilation album titled Women in Jazz: Swing Time to Modern, Volume 3 in 1978. However, these albums also went out of print soon thereafter.

- 21 Redd, interview with Monk Rowe (13 February 1999).

- 22 Vi Redd, 2009.

- 23 Leonard Feather, liner notes for Lady Soul (Atco 33-157, 1963).

- 24 Stanley Cowell, personal communication with author (15 May 2005).

- 25 Longo, 2005.

- 26 Ibid.

- 27 Bailey, 2005.

- 28 Ibid.

- 29 Redd, 1999.

- 30 Cowell, 2005.

- 31 Ibid.

- 32 Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought (New York and London: Routledge, 2000), 105.

- 33 Cowell, 2005.