American Music Review

Vol. XLII, No. 2, Spring 2013

By Stephanie Jensen-Moulton, Brooklyn College, CUNY

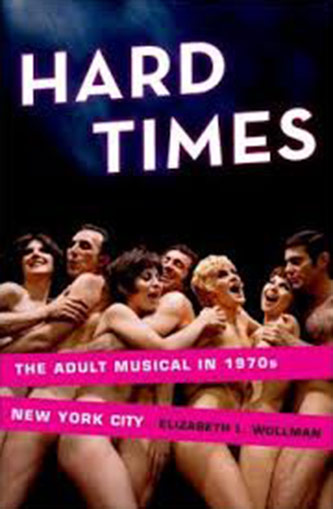

When we think of adult themed musicals, Hair (1967) is usually the one that comes to mind. Elizabeth Wollman acknowledges this in her superbly written and expertly researched monograph, Hard Times: The Adult Musical in 1970s New York City (Oxford University Press, 2013). Like the genre itself, Wollman's book drops its figurative robe on the first page, opening the door for frank discussion of sex, an essential element of the 1970s adult musical. The musicals Wollman covers in her nine-chapter work have been influenced by aspects of the sexual revolution, and the related feminist and gay rights movements of the era. Despite these somewhat left-leaning underpinnings, all of the musicals discussed in Hard Times were aimed at mainstream audiences, on and off Broadway. Wollman takes a comprehensive approach that examines not only the hit shows, but also Off Broadway musicals, straight dramatic plays, and influential films. This holistic perspective also includes extensive research on the contentious political climate into which these shows emerged. In her introductory remarks, Wollman recognizes that those who participated in the creation of these musicals may not reflect upon them with kindness or pride, and therefore, the research materials have not always been preserved with care, nor have interviews been consistently easy to procure. Nevertheless, Wollman has taken up the false floorboard and revealed a stash of treasures that have been hidden away for decades.

Hard Times: The Adult Musical in 1970s New York City

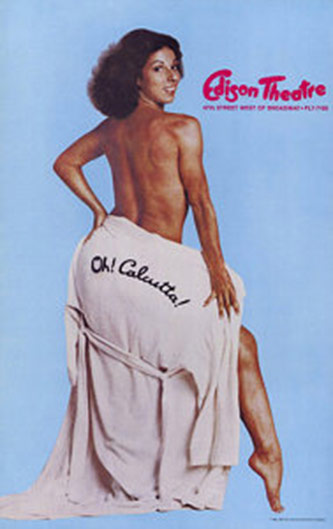

In her first chapter, Wollman ventures Off-Off-Broadway to explore some of the roots of the adult musical in straight plays and burlesque. Within a year of Hair's opening, two very early adult musicals opened which bore the hallmarks of the revolutions off the Great White Way. We'd Rather Switch (1969) is essentially a burlesque show-within-a-show with all of the gender roles reversed. Kenneth Tynan's Oh! Calcutta! (1969),with its "encounter group" sessions to facilitate the actors' comfortability with nudity and simulated sex acts, would be one of the most-remembered adult musicals of the era, and one of the longest-running. In spite of, or perhaps because of, its extremely rigid views of human sexuality, Oh! Calcutta! found a way to speak to audiences that the other, perhaps more radical early adult musicals did not.

Wollman's second chapter is remarkable in that it treats in full a cultural interpretation of Bobby, a character in Sondheim's Company (1970). She interprets him within the context of other stage works of the time, particularly the brand of post-Stonewall gay theater that erupted out of a Greenwich Village coffee shop, the Caffe Cino. Wollman traces a trajectory from the important early gay play The Boys in the Band (Mart Crowley, 1968) through Company and other early gay musicals. As she so astutely points out, much of the cultural work that subsequent gay musicals did was to dismantle the erroneous notion of gay depression through the joyous expression of gay life on stage. Wollman suggests that Bobby's role in Company, with his sexual ambiguity, was a centering figure for gay men of the 1970s, who flocked to the musical, seeming to identify with him. She even includes a section of dialogue cut before the New York premiere that alludes to a possible sexual connection between Bobby and his friend Peter. The closeted gay characters in musicals and plays at the beginning of the decade would soon strut their way out into the open via the gay musical of the mid-1970s.

Chapter 3 opens the door on a rich tradition of gay musicals which, until Wollman's book, have been largely unknown. With titles such as The Faggot (1973) and Let My People Come (1974), these stage works brought to mainstream audiences the novel idea that life as a gay person could be wonderful but sometimes heartbreaking; in other words, like life for everyone else. Al Carmines's The Faggot reveals both these sides of gay life in one of the longest-running musicals—more than 200 performances after the run was extended—to come out of the Judson Poets' Theater. The racier but less socially forward-looking Let My People Come: A Sexual Musical was created by composer/lyricist Earl Wilson Jr. and director Phil Oesterman, who felt that Oh! Calcutta! was a peep show worthy of their parents' generation. They wanted to create a musical that explored a variety of sexual experiences, including contemporary gay life. Other musicals with gay content such as Lovers (1974), Sextet (1974), Boy Meets Boy (1975), and Gay Company (1974) wove different stories of human sexual relationships. But as Wollman asserts, despite their diversity of content and style, they were united by spectators who "were eager to be entertained but not averse to also being educated about contemporary gay men. The most successful musicals of the bunch were less angrily preachy than they were gently, persuasively inclusive." (p. 87) This, Wollman asserts, proves to be the uniting theme for the entire era of adult musicals and their reception.

Chapter 4 carries the thread of "gentle inclusivity" to its logical extreme: second wave feminist musicals. The first musical to explore the women's movement of the 1970s in depth was Myrna Lamb's Mod Donna (1970), which Wollman couches in the context of Hair's dependent female characters and the heterosexual politics ofOh! Calcutta!. Mod Donna, however, did not connect with mainstream audiences because of its overly aggressive representations of blaming, bra-burning lesbian feminist women who wanted to tell men a thing or two about patriarchy. The reviews varied widely according to the political views of the critics, and in the end the show closed after a brief six week run.

Feminist musicals that emerged later in the decade were more "palatable" to audiences because, as Wollman asserts, the women's movement was well underway and therefore not as threatening to the general public as in 1970. In Chapter 5, Wollman pairs Eve Merriam's The Club (1976) with Gretchen Cryer and Nancy Ford's I'm Getting My Act Together and I'm Taking It on the Road (1978), exploring two vastly different approaches to musical theater. While The Club is a cross-gendered, turn-of-the-century-style burlesque play-within-a-play, the Cryer/Ford piece is an intimate, autobiographical show featuring a popular music aesthetic. This chapter accomplishes two scholarly goals: we learn about two more important but overlooked examples of musical theater, and also hear about work composed by, for, and about women, a triumvirate that rarely occurs even now. Yet, while both of these musicals were sexy, neither of them was particularly sexual. Wollman's next chapter connects the overt sexuality of the "porno-chic" movement with the convenient "conflati[on] of the women's movement and the sexual revolution." (p. 129)

As the author explains, a significant prong of the women's movement in the 1970s connected intimately with female sexuality, which had been transformed with the advent of the birth control pill in the 1960s. Dueling narratives disseminating popular conceptions of women's sexuality could be found in Playboy and Cosmopolitanmagazines. While the former exploited and objectified women's bodies, the latter empowered women to claim their bodies and to enjoy sexuality— albeit within heterosexual relationships, and within androcentric models of "acceptable display." (p. 133) These issues come to a head with the rise of porno chic, a brief but intense movement that surrounded the release of the successful porn film Deep Throat in 1972. Wollman takes a moment in this chapter to explain the quickly changing climate surrounding obscenity laws in the United States, and how these would affect the distribution of mainstream pornography. What makes this film particularly relevant is its focus on female sexuality: the entire premise of the film is the strange location of the female lead's clitoris in the back of her throat. Deep Throat thus polarized the debate: was the film about the possibility of women's sexual satisfaction, or about fetishization of the male organ? And was it the catchy soundtrack that made the film sell? Whatever the reasons, Deep Throat succeeded at the box office, spawning a myriad of other porno chic wannabes. The trouble with musicals that took porno chic as their cue was that they often embraced a patriarchal model of sexuality. In Let My People Come, the songs about gay life feature fully clothed men, whereas the one about lesbians asks the women to appear nude and in position for oral sex. According to Wollman, the song "Come in My Mouth" presents a typical pornographic scenario of fellatio, but in the context of a musical the "money shot" of the eventual orgasm is lost because the woman's climax is invisible. This, in a nutshell, encapsulates the feminist debate of the time.

ArtsFuse.org">

ArtsFuse.org">

Oh! Calcutta (1976 revival) Photo courtesy of ArtsFuse.org

It was a small step from porno chic musical to hard-core pornographic film musicals. Wollman discusses two from the latter genre. While Alice in Wonderland: An X-Rated Musical Fantasy (1976) and The First Nudie Musical (1976) could not have been more different in character or conception, they each featured so much distracting nudity that any would-be feminist narratives were lost. For instance, Alice, originally an uptight librarian, learns many different modes of sexuality while in the fantasy world. But in the end, she returns to heteronormativity and patriarchal propriety by giving it up for her boyfriend, the one who told her she was repressed in the first place. The First Nudie Musical took its cue from early film, using a film-within-a-film model. One might almost think, given its madcap plot, that the film had been made in the 1930s, except that all of the women are fully nude. In one dance number, the women wear only dinner jackets and shoes, while the men are fully clothed. Despite these discrepancies, the author points out that the women in the film are generally empowered, taking the lead in saving the day and making the men around them look foolish and bumbling. Wollman also takes note of one hardcore stage musical, Le Bellybutton (1976), that tried to be a spoof of Oh! Calcutta!, but failed at being either a successful musical or a successful package for the delivery of pornography.

In Chapter 8, Wollman details the complexities of changing laws surrounding the use and distribution of pornography in New York City. This is obviously relevant, given that many of the musicals mentioned herein featured nudity, and several featured simulated sex acts. The authorities began to draw the line when Lennox Raphael's musical Che! based on the life of Che Guevara, began its previews in 1969. While the acts of nudity and sexuality performed in Che! brought nothing new to the jaded eyes of New York theatergoers, it was one detail that proved problematic for the production team: they encouraged the actors to actually perform the sexual acts, rather than simulate them, whenever possible in the staging. Wollman succinctly addresses the New York State and City obscenity laws and how they related at the time to the repeated closing and fining ofChe! for obscenity—regardless of its venue. Let My People Come was deemed "lewd" but not obscene, but nevertheless had some of the same troubles as Che! in finding and staying in a venue, particularly since its run was exponentially longer.

Wollman's final chapter juxtaposes Let My People Come with I Love My Wife (1977), a musical featuring two heterosexual couples who are really afraid to be swingers. These seemingly strange musical bedfellows—one that lets audiences face their fears about the sexual revolution and their potential role in it, the other, a nudie lewdy favorite that reads like a live, staged porn film—allows readers to understand the complexity of the artistic climate between the 1960s and 1980s on and off Broadway. Wollman takes a topical, non-linear approach rather than applying chronological methodology, thereby illuminating her subject matter through the context of other musicals of the time. As she concludes, mainstream audiences found the adult musicals of the 1970s a "curiously comfort[ing]" way to experience at least some part of the sexual revolution of this tumultuous era on their own terms.