American Music Review

Vol. XLI, No. 2, Spring 2012

By John Wriggle, Los Angeles, CA

Composer-arranger Eddie Sauter (1914–1981) frequently receives the epithets of "advanced," "ahead of his time," or a "foreshadow" of better-known figures. Early in his career working in jazz and popular music, Sauter's reputation for studying under multiple conservatory composers associated with European modernism set him apart from the self-taught image cultivated by many of his Swing Era peers, or even those who aligned themselves with the more populist pedagogy of Joseph Schillinger. Historians and jazz critics have had difficulty classifying Sauter's musical style: too classically-influenced for mainstream jazz purists, yet too commercial for the Third Stream clique. Individual listeners' tastes tend to determine whether Sauter's experiments with modernist techniques like serialism represent a pioneering of, or pandering to, the glitzy "progressive"-pop studio orchestra sound that emerged in the late 1940s.

George E. Lewis has noted the "lack of framework for examining post-Jazz Age interpenetrations between jazz-identified musics and contemporary European American musical experimentalism."1 The stylistically inclusive aesthetic of Sauter's music remains difficult to place into existing frameworks of genre or style. To associate the arranger with the white "progressive jazz" marketing strategy of bandleader Stan Kenton—whom Sauter never did work with—does little to explain the continued championing of Sauter as a persistently subversive figure in either jazz, popular, or experimental music. Nevertheless, the lack of a music history paradigm accounting for the contributions of arrangers who endured charges of "middlebrow" hybridity or formulaic commercialism for much of the twentieth century has offered Sauter's legacy few other resting places.

Music from the Sound Track of Mickey One (MGM Records, 1965)

A New York native, Sauter began his career in the 1930s working for local swing dance bands, first as a trumpeter sideman-arranger for Red Norvo, then as a freelance arranger for Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw, and Benny Goodman. Celebrated arrangements like "Superman," recorded by Benny Goodman in 1940, significantly departed from established Swing Era standards of orchestration, tonality, and formal structure. Later in his career, Sauter recalled that Goodman "didn't play this stuff for a long time because he used to complain they were too classical."2 Indeed, Goodman was notoriously unsupportive of Sauter's more daring orchestrations, dismissing his ensemble of the period as "a rather affected kind of band" and charging that Sauter "wasn't really a jazz man"—an indication of artistic tensions that only added to the arranger's reputation as a nonconformist.3

It may be ironic that the close of the Swing Era saw Sauter's turn to a career as a popular dance band leader. The successful orchestra he co-led with arranger Bill Finegan during 1952–57 featured multiple pitched-percussion instruments and (then) eclectic woodwind doublings. In a 1952 puff piece for Down Beat, Sauter boasted:

Musicians who've listened to the sides we made can't figure out how we got some of the tonal combinations, some of the percussion effects. Don't you think we should keep the [photographic] pictures of the date from being printed? There are certain sounds we'd like to keep as our identification.4

Sauter–Finegan hits like "Doodletown Fifers" (New Directions in Music, 1952) influenced the pop studio orchestra recordings of the hi-fi LP era and helped to usher in a studio percussion fad that paralleled the advent of stereo. The success of the orchestra's RCA-Victor releases fueled competition from contemporary arranger-conductors such as Juan Esquivel and Pete Rugolo.

After his orchestra disbanded, Sauter returned to freelance work for the remainder of his career, directing a West German radio orchestra, providing string orchestra backings for saxophonist Stan Getz's 1961 album Focus, and writing jingles and cues for television programs, including Rod Serling's Night Gallery. In 1969, Sauter orchestrated the Tony Award-winning Broadway musical 1776, later made into a Columbia Pictures film (1972). The arranger was interviewed by Bill Kirchner for the Jazz Oral History Project in August 1980, less than a year before his death.

The quantity and breadth of Sauter's surviving music manuscripts is tantalizing. Archival holdings include Yale University's Red Norvo Papers, which preserve Sauter's earliest work from the 1930s. The Benny Goodman collections at Yale and the New York Public Library, along with the Artie Shaw collection at the University of Arizona, hold scores and orchestra parts reflecting Sauter's early-1940s arrangements. Scores for Ray McKinley's orchestra of the late 1940s reside at the Smithsonian Institute. And the Eddie Sauter Papers, also held at Yale, contain material from the 1950s Sauter–Finegan orchestra, Getz's Focus album, and the musical1776.

Included among the Yale Sauter Papers are the nearly complete manuscript scores and orchestra parts for Arthur Penn's 1965 film Mickey One, Sauter's only original, feature-length film score. (The Kirchner interview suggests that another Sauter-scored film, Felicia, was completed but never distributed). Penn's film was a self-conscious plunge into the aesthetics of the French New Wave, and explicitly experimental in both its visual and audio construction; New Wave filmmakers Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut both visited Penn on theMickey One set during filming. Mickey One incorporates a number of avant-garde filmmaking techniques that would become Hollywood staples by the 1970s (often via Penn's own films like Bonnie and Clyde), but their execution in this early effort was awkward and confusing for some viewers. Penn himself admitted, "I may have overshot my mark ... I was really operating on the symbolic and metaphorical level without engagement between audience and screen."5 He later dismissed Mickey as "a sort of avant-garde, kooky film."6 But regarding the music, Penn reflected: "you never know at the time you're doing it that it's important, until it's way over. When the picture came out, and then I listened to the score by itself, I thought, my god, this is extraordinary."7

Though finally made available on DVD in 2010, Mickey One remains largely forgotten today. Yet the film represents an astounding audio feat. The score's large-scale fusion of improvisation and atonal-influenced orchestral scoring remains one of few such efforts in American cinema. When asked by Kirchner about the project, Sauter revealed pride in his efforts:

Most of the stuff I do I can't listen to, but I can listen to that [Mickey One]. ... What I try to do is string them [the cues] together in such a way that it made one big piece. ... The ability to pick up on a theme and work it through was always a ball ... maybe that's why I like Mickey One.8

Sauter's thematic-motivic constructions for Mickey One are combined with aleatoric ensemble improvisation and cinematic audio montage production techniques. The sheer amount of music created—forty-six scored cues—can be overwhelming, especially as heard in the film, where it is combined with audio elements including broken pianos, junkyard trash compactors, building demolitions, train whistles, microphone feedback, nightclub audience noise, and a penny-arcade machine gun that emerges as its own thematic audio identity. Nevertheless, examination of the scores in the Sauter Collection, along with material issued on the MGM albumMusic from the Soundtrack of "Mickey One," reveal that Sauter's score was significantly cut down in the final film release. While such cutting is standard practice in Hollywood cinema, it is especially frustrating that Mickey—about which its own director rued, "it would have been so easy to tell a really simple narrative ... a binding one"—saw so many cuts to a key component that might have helped to hold the film together.9 As many as ten cues were cut completely; within the cues that remain in some form, it is often the passages of recurring thematic material that were trimmed.

The prominent billing of featured soloist Stan Getz, then at the height of his popularity as the "Bossa Nova King," was not all hype; nor was his onscreen credit for "improvisations." Getz is featured in a majority of the film's cues, and although Sauter often assigned the soloist a thematic melody as reference, Getz's adherence to these parts tended to be quite loose—occasionally he ignored the parts completely—and a number of cues feature extended improvisations. Within Sauter's soundscape, Getz's saxophone serves as the musical personification of the film's protagonist (Mickey, played by Warren Beatty) through the thematic identity of "Mickey's Theme," also titled "Mickey's Lament." Getz's improvisations create additional layers of interpretation amid Penn's New Wave audio-visual disjunctions, providing romantic embellishment or ironic commentary on the film's visual imagery or underscore music themes.

Mickey's references to the film noir genre, another New Wave nod, include parallels with "crime jazz" scores like The Sweet Smell of Success or The Man With the Golden Arm: plunger-muted brass solos, Latin rhythms (Bossa Nova for Mickey One, of course), and brass section shakes. But Sauter's score adds much more to the mix, featuring "extended" orchestration techniques, expanded percussion instrumentation, and the use of overdubbing and overlay tracking. Time signatures are overlapped across orchestral sections, tempos frequently and abruptly ramp up or down, and multiple recorded cues are overlaid simultaneously in portions of the final audio mix. The film's story of a nightclub comic-singer, on the run from the mob and working in seedy bars and burlesque venues, necessitated an additional layer of diegetic (onscreen) music scored for smaller combos.

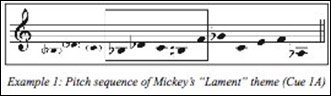

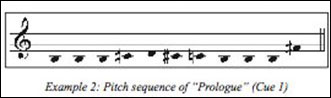

Sauter's "Lament" theme is first introduced in full as Mickey learns that the mob is calling in his debts. It's a haunting melody, featuring a number of dissonant chord extensions, and throughout the film it is almost exclusively presented by Getz, in some instances unaccompanied. Different settings of this melody accompany scenes of Mickey living on the lam, his interactions with a waitress character he decides he cannot have a relationship with, and an intimate apartment conversation with his later girlfriend, Jenny. It also returns in the film's mid-point flashback sequence, and amidst or adjacent to other cues reflecting Mickey's emotional state. At least two intended iterations of the "Lament" theme were not included in the final film cut. The first pitches of the "Lament" theme (see box in Example 1) might be described as Sauter's "Mickey motive." This motive reappears verbatim or transposed in a number of the film's cues, including the introductory flute figure and Getz's saxophone solo in the opening title sequence ("Prologue"; see excerpt in Example 2), and—in a radically different orchestration of low brass and strings—when Mickey steals a taxicab.

Example 1: Pitch sequence of Mickey's "Lament" theme (Cue 1A)

Example 2: Pitch sequence of "Prologue" (Cue 1)

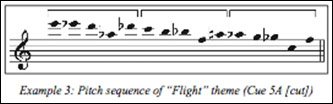

The first appearance of the "Flight" theme precedes the striking occurrence of three overlaid, unaccompanied Getz improvisations; the soundtrack album release includes Getz's triple-improvisation as "Mickey's Flight." This layered improvisation is also derived from the Mickey motive, heard here in the guise of a blues lick. The violins' fast "Flight" theme, occasionally doubled by glockenspiel and accompanied by percussive dissonant chords (parallel diminished-seventh chords voiced a half-step apart), includes "Mickey motive" variations as well, displacing the first five notes of the "Lament" theme (Example 3). The "Flight" theme was also scored to close the mid-film flashback sequence—a cue eventually cut from the film.

Example 3: Pitch sequence of "Flight" theme (Cue 5A [cut])

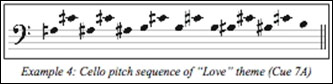

Most instances of the film's "Love" theme are scored for violins, supported by a cello counter-melody. In addition to the violin's theme, the chromatic ascent of the cellos' lower notes (Example 4) suggest an ascending variation of the Mickey motive; the upper contour of the theme's first six bars likewise recalls the opening sequence of the "Lament" theme. Getz generally improvises over the "Love" theme orchestral cues.

Example 4: Cello pitch sequence of "Love" theme (Cue 7A)

Sauter's "Hymn" theme, "Is There Any Word (From the Lord)," becomes a key plot element, as Mickey himself asks this question throughout the film. The theme is initially heard as diegetic music performed by a Salvation Army marching band, where it is accompanied by Getz's non-diegetic performance referencing the "Lament" theme. Built around transpositions of the Mickey motive, Getz's part is intentionally out of key with the brass theme. Even as Getz veers away from the written part following the initial motivic references, Sauter's desired effect of dissonant loneliness—the score indicates "mumble [lonely as hell]"—is maintained in both the film and the soundtrack album performances (the album uses a different take than the film). This first appearance of the "Hymn" theme was originally scored to end with a more explicit restatement of the "Lament" theme—another passage cut from the film.

At the climax of the narrative, Mickey's entrance into a red light district is accompanied by a trumpet-led jazz combo track overlaid with rock band and stride piano cues previously heard as diegetic music. An ensuing street fight pits an orchestral version of the "Love" theme against the onscreen violence, and the audio eventually breaks down into a chaotic jazz combo improvisation. Music cues preceding and following this sequence are also overlapped, resulting in a remarkable audio mélange.

The primary themes return at the end of the film, following Mickey's searching return to the junkyard. After the "Artist" character's beckoning call on flute, we hear a variation of the "Love" theme, then a Getz performance of the "Lament" theme; the cue closes with Getz's repetition of the Artist's flute phrase that opened the cue (the film and soundtrack album reflect different takes at this point). Through this crossing of the diegetic flute music into Getz's non-diegetic underscore performance, Mickey accepts the call of the Artist. He returns to the nightclub stage, where the "Hymn" theme returns to close the film.

Due to the sheer amount of sound heard in Mickey One, cuts to the film score were probably inevitable. Budget was apparently an issue as well, as Penn recalled of the scoring session that he was "running out of money like crazy at this stage."10 But it is clear that Sauter's surviving scores and the additional music documented in the soundtrack album reveal a much more comprehensive narrative conception than what is already heard in the film. Sauter's orchestrations carry his themes through a staggering array of textures that offer both consistent invention and structural coherence. Despite its partially realized state (a situation that could well be rectified by a performance of the complete original score), the film score for Mickey One remains a triumph of the American commercial music arranging tradition, and Sauter's own unique sound and style.

Notes

- 1 George E. Lewis, A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 375.

- 2 Eddie Sauter, interview by Bill Kirchner, 11 August 1980, Jazz Oral History Project, Smithsonian Institution Division of Performing Arts, Washington, D.C.; transcript on file at the Institute of Jazz Studies, Newark, page 113.

- 3 Benny Goodman, as quoted in Richard Sudhalter, Lost Chords: White Musicians and Their Contribution to Jazz, 1915–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 564.

- 4 Eddie Sauter, as quoted in [Leonard Feather], "Sauter-Finegan Create Band with 'New Look'," Down Beat(16 July 1952): 1, 19.

- 5 Arthur Penn, as quoted in Joseph Gelmis, The Film Director as Superstar (New York: Doubleday, 1970), 221.

- 6 Arthur Penn, as quoted in Doug Ramsey, "Reissuing Stan Getz Plays Music From the Soundtrack of 'Mickey One'" [liner notes], Stan Getz Plays Music From the Soundtrack of "Mickey One" (Verve 314 531 232-2, 1998).

- 7 Ibid.

- 8 Sauter, interview by Kirchner, 238–241.

- 9 Penn, as quoted in Gelmis, 221.

- 10 Penn, as quoted in Ramsey.