American Music Review

Vol. XLI, No. 2, Spring 2012

By Deane Root, University of Pittsburgh

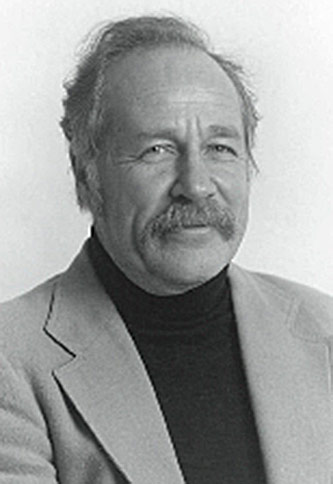

Charles Hamm (Charlottesville, VA, 21 April 1925; Lebanon, NH, 16 October 2011) was among the first musicologists trained in European musical philology and manuscript studies to embrace the study of American and popular music. This made him among the earliest to pursue research simultaneously on musical practices that were oceans and centuries apart from one another, a career practice now widely emulated.

Charles wrote his own characteristically self-effacing obituary that was circulated via websites and email to multiple scholarly societies. It conveys the basics events of his life, but not his personality, quality of mind, or influence. He served in the Marine Corps in World War II, completed a BA in music at Virginia in 1946, and earned the MFA in composition at Princeton in 1950 before accepting a teaching position at the Cincinnati Conservatory where he wrote songs, piano pieces, a Sinfonia for orchestra, and an opera, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (after James Thurber's story). In 1960 he returned to Princeton to study musicology, then taught at Tulane where Gilbert Chase encouraged his American studies. When the Princeton faculty had denied Charles's re- quest to write a dissertation on an American topic, he produced a path-breaking study on Guillaume Du Fay, but the music of his own culture continued to intrigue him more. In 1963 he moved to the University of Il- linois where he taught musicology, founded the Archive for Renaissance Manuscript Studies and co-edited the Census Catalog of Manuscript Sources of Polyphonic Music, 1400–1550 (1979–88). He also taught courses in American and popular music and participated with composers including John Cage in new-music concerts and poker games. From 1976 he was professor at Dartmouth, and held many visiting appointments in the US (including a research fellowship with I.S.A.M. at Brooklyn College in 1986) and South Africa. He was president of the American Musicological Society (1973–74), a founding member and two-time chair of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music, and recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Society for American Music (2002).

Charles Hamm (1925-2011)

His analytical approach to identifying and solving musical questions perhaps stemmed from his early undergraduate training in engineering, and made his teaching and research particularly lucid and revealing of patterns and practices. At Dartmouth he found time to write book-length studies of topics he had begun developing in his courses. Yesterdays: Popular Song in America (1979) was the first history of the topic by a musicologist; he followed it with a collection of his essays titled Putting Popular Music in its Place (1995), as well as a mono-graph for I.S.A.M., Afro-American Music, South Africa, and Apartheid (1988). Meanwhile he produced a textbook, Music in the New World (1983), which won the Society for American Music's Lowens Award. Still used in courses today, the text is organized partly around the set of 100 LP recordings of American music that launched New World Records as a Bicentennial project. Besides reviews, papers for conferences, and articles on avant-garde composers and the popular music of South Africa and China, he turned attention to the most widely heard twentieth-century songwriter through his book Irving Berlin: Songs from the Melting Pot (1997) and a three-volume MUSA edition of Berlin's Early Songs (1994). His last edition, done in col- laboration with Elmar Juchem and Kim H. Kowalke, was the beautifully prepared volume in the Kurt Weill edition series, Popular Adaptations 1927–1950 (2009).

Charles's legacy of publications is matched by his influence on students, as a teacher, role model, mentor, and friend. He made any music he taught seem fresh and fascinating, participated with students in performing the pieces being studied, and made learning a partnership in discovery. His approach to new music was not altogether different from teaching early notation: the people who wrote this music displayed great intelligence, he reminded us; our task is to discover their logic and understand how the music makes sense.

Many of his former students became lifelong friends. He treated them all with courtesy, respect, humor, warmth, and the gentle manners befitting a Virginian, and enjoyed engaging them in games of tennis, golf, cards, and Upwords.

He donated some of his papers to the Center for Black Music Research at Columbia College Chicago, and much of his popular- and American-music collection to the Center for American Music at the University of Pittsburgh. A memorial gathering of family, friends, and students met at the Norwich (VT) Inn, maker of Charles's favorite martinis, on 3 December 2011. He is survived by a sister and brother, his three sons Bruce, Chris, and Stuart, four grandchildren, two former wives, and legions of students. All who study American-music history and popular music are in his debt.