American Music Review

Vol. XLI, No. 2, Spring 2012

By Alex DiBlasi, St. John's University

It is an unfortunate truth that performers and artists who were overlooked, unappreciated, or reviled in their time only gain critical acclaim and attention in death. When this article was first conceived, Davy Jones (1945–2012) was still alive, viewed by many Monkees fans (including this author) as the proverbial stick in the mud, the one who warned his bandmates to stick with the formula that yielded commercial success rather than challenge the whims of their management. He was the one who always went to the press with overtly critical and spiteful comments about his cohorts, most recently after the abrupt cancellation of their summer tour. Although Jones was the least innovative of the four Monkees, one can only hope that the band as a whole will still receive the critical reappraisal that should come with his passing.

The Monkees have never quite been able to enjoy their moment in the sun. In their time, the burgeoning rock press viewed them as an instrument of the music industry, an example of plastic pop marketing creeping its way into the "authentic" world of rock music. Their first reunion in the 1980's was marred by bad publicity and a refusal to play ball with the media, with subsequent reunion efforts being greeted with increasing levels of derision and internal friction. Although they have been eligible since 1991, The Monkees have never been considered for inclusion in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, an embarrassing fact that says more about the music industry than it does about the band. Beneath the pop façade, the one that made the group such a punch line among critics, scholars, and rockists, were creative forces that were innovative, subversive, and groundbreaking.

The Monkees, May 1967, From left: Mickey Dolenz, Davy Jones, Mike Nesmith, and Peter Tork

In the wake of the 1960s British Invasion, American music executives sought to find their answer to The Beatles. Using The Beatles' feature films as inspiration, Screen Gems commissioned a sitcom about a fictional band, issuing a callout for actors. The show's producers finally settled on four young men—two actors (Englishman Davy Jones and California native Micky Dolenz) and two musicians (Texan Michael Nesmith and East Coaster Peter Tork)—who were cast based on their comedic sensibilities and the fact that they could sing. It was little more than an update of the old school pop music assembly line, with quality songwriters and session players backing up four vocal talents. To that end, it is worth noting that the group's debut single, "Last Train to Clarksville," went to the top of the charts before the series hit the airwaves in September 1966.

The show fared well with its intended audience, and their singles were smash hits, but it was not long until the mainstream press began shedding light on the manufactured nature of the band. An insightful article from the January 1967 Saturday Evening Post by Richard Warren Lewis was the first (but hardly the last) piece to detail the activities of The Monkees. In the first of many instances of the man's mercurial relationship with the media, it was Michael Nesmith who gave some of the most damning quotes: "The music has nothing to do with us," he said, adding to Warren that he should "tell the world that we're synthetic, because, damn it, we are. Tell them The Monkees were wholly man-made overnight [...] Tell the world we don't record our own music." Despite Nesmith's scathing account of the musical end of The Monkees, he was quick to speak in defense of the show: "But that's us they see on television. The show really is part of us."1

Nesmith's words surely rattled the chains of the man in charge of the band's musical endeavors, Don "Man with the Golden Ear" Kirshner. Kirshner had positioned himself as the Svengali responsible for the group's fortunes; the last thing he needed was dissent from the ranks, especially anything that shattered the illusion. That said, Nesmith's call for the world to acknowledge the band's manufactured origins could not have been much of a surprise to Kirshner, who had stated from the beginning of The Monkees' recording career that their success rested on Jones's cutesy charm and Dolenz's McCartney-esque singing voice, not on Tork or Nesmith's desire to have The Monkees actually exist as a band. Kirshner's grip on the band was forced loose in his failed efforts to maintain control over The Monkees, with regard to both their public persona and their increasing desire to have more input in the studio.

Matters began to upset even the relaxed Dolenz when the band learned, while on the road, that their musical director had released the second Monkees album, More of the Monkees (1967) without their input. The guys found nothing to like about the album, from the butchered cover photo (originating from a print ad they had shot for JC Penney) to Kirshner's liner notes on the back of the LP praising both himself and all the songwriters who made this disc—in the Golden Ear's own distorted reality—the most important platter of vinyl in the history of recorded sound. No less than nine producers were used in the course the making of the album, making for a remarkably uneven listen. The record has its highlights—"She," written by Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart, the duo responsible for the show's theme song and "Last Train To Clarksville," Nesmith's "Mary, Mary," and Gerry Goffin and Carole King's dulcet "Sometime In The Morning" are all included on best- of compilations—but it was mostly saccharine pop of a decidedly un-cool ilk. The absolute nadir came with Jones's spoken lyric on the laughable "The Day We Fall In Love."

In an act of defiance, the quartet, with friend and former Turtles bassist Chip Douglas in tow as producer, sojourned to the studio to record two songs as a band. The resulting songs, "All of Your Toys" and Nesmith's "The Girl I Knew Somewhere," show a band with legitimate musical skills.2 With time, the group triumphed over Kirshner, specifically after he authorized a single release credited to "Davy Jones—My Favorite Monkee" in a last-ditch effort to woo Jones away from the other three, who had firmly stated they wished to record their third album as a group. Kirshner was summarily dismissed as the band's musical director, although twenty years later he still arrogantly declared, "It was the only job I ever got fired from!"3

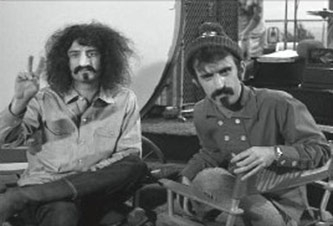

Mike Nesmith as Frank Zappa and Frank Zappa as Mike Nesmith, Still from the TV Episode "The Monkees Blow Their Minds" (1968)

With Kirshner out of the picture and the foursome of Nesmith, Dolenz, Jones, and Tork eager to prove themselves as a proper recording act, they began work on what became the Headquarters album. Tork was easily the most fluent musician of the group, playing guitar, bass, banjo, and keyboards on the album; Nesmith established himself as a competent guitarist and vocalist, having much more of a presence on this album than the first two releases; and Jones took a few stabs at keyboards and drums. The only member of the group whose skills are up for debate is Dolenz, who tries his chops as a drummer.

However laborious the process to make it may or may not have been, Headquarters shows that The Monkees could have been a "real" band from the start. The band's chemistry rests in the ear of the beholder, but the album possesses an authentic passion that predicts the independent rock that came in the early 1980's. Aside from Douglas occasionally filling in on bass while Tork played keys and the orchestral session men used on "Shades Of Gray," the album features only the four Monkees. Upon its release, in May 1967, it shot to number one. In a bittersweet twist, the following week Headquarters was unseated by Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band; their album would sit at number two for the remainder of the summer, symbolizing the press's view of the Monkees as a pre-fabricated response to the genuine article.

Eric Lefcowitz's Monkee Business remains one of the few books that presents and defends the band and their efforts to break free of the pop machine. On the subject of The Monkees being branded as "fake" by the hip circles of the time, Lefcowitz writes: "Authenticity, or at least the appearance of it, was suddenly crucial. It didn't matter that only one member of The Byrds, Roger McGuinn, had played on ‘Mr. Tambourine Man,' or that Pet Sounds was practically a Brian Wilson solo album even though it was credited to The Beach Boys."4 He raises a salient point, one that this author frequently points to as an argument for The Monkees' validity as a recording entity. That said, he sheds some light justifying this mindset: "Those bands [...] were viewed as organic musical ventures while The Monkees and their TV show were not."5

They may have started as little more than a marketing strategy for the bigwigs to create their own Beatles—complete with weekly TV adventures—but what set The Monkees apart from other readymade pop entities was their desire to be a real band. They staged a coup that resulted in them becoming their own musical directors. After two albums recorded by the band as a unit, all four members found themselves helming their own sessions. Each member pursued their own muses, working on the music they enjoyed the most. They may have both been at odds over the group's artistic directions, but Jones and Nesmith proved to share a workaholic mentality in the studio, producing a prolific body of work.

Although they were largely savaged in the press, The Monkees did have their share of allies in unlikely places. Animals front-man Eric Burdon came out in defense of the group, com-paring them to "a record production group" akin to Phil Spector's stable of stars, urging that listeners "just enjoy the record."6 In early 1967, the four members of the band went on individual press tours of England. Dolenz found himself invited to Paul McCartney's London apartment, where he was treated to a preview of the "Penny Lane" / "Strawberry Fields Forever" single, as well as the opportunity to smoke marijuana with the Beatle. Tork found a kindred spirit in George Harrison, who later invited him to play banjo on the soundtrack album to the film Wonderwall that following year. Nesmith was invited to attend the famous recording session for the orchestral swells that punctuate "A Day In The Life" from Sgt. Pepper, where John Lennon told him he was a fan of their show and compared them to the Marx Brothers.

Domestically, the band had even more public support. Tork had become a member of Los Angeles's hippie elite, being best friends with Stephen Stills and partying with the likes of Neil Young, Cass Elliot, and Buddy Miles. Perhaps the most unlikely fan of the group was Frank Zappa. In a particularly memorable segment, he appeared alongside Nesmith in the pre-credits sequence of the season two episode, "The Monkees Blow their Minds," with each of them dressed up as the other. The pair make some self-effacing jokes before Nesmith conducts Zappa as he destroys an old car with a croquet mallet, all set to Zappa's song "Mother People." Zappa would also make a cameo in The Monkees' 1968 film, Head, playing a sarcastic critic who tells Jones that his performance of "Daddy's Song" was "pretty white." Dolenz also claims in his book that Zappa invited him to drum with The Mothers Of Invention, but could not accept due to contractual obligations.7 Some two decades later, Zappa quipped to Indiana University rock music professor Glenn Gass that The Monkees were "the most honest band in Los Angeles."8

The group's biggest influence on popular culture rests in the television program which served as their genesis. The Monkees combined the anarchic humor of the Marx Brothers with the fast-paced, dynamic visual style of Richard Lester, director of The Beatles' first two motion pictures, A Hard Day's Night (1964) and Help!(1965). Each member of the band had their own distinct personality: Jones was "the cute one," while Dolenz was the madcap, Nesmith the wry one, and Tork the lovable goof. The group dynamic, however staged it may have been, was believable.

The show played an essential role in shaping what would become the music video. In his memoir, I'm a Believer, Dolenz downplays this, pointing to filmed musical segments dating as far back as sound cinema all the way up to Lester's films with The Beatles. Much like the raging debate over who really started punk rock or whotruly invented the blues, the discussion over the origins of the music video is potentially never-ending. It is worth crediting The Monkees because of the wide variety of styles used in presenting their songs. Sometimes the songs were incorporated into the episode as a chase or party sequence, other times as part of a montage, and occasionally as a filmed segment of the band performing.

As the series progressed, all four Monkees sought to bring their own interests into the show. In instances where an episode ran short in the first season, the producers would pad out the remainder of the half-hour with an interview with one or more of the band. During the second season, the four had more of a say in what was featured. In one episode, Jones and his friend Charlie Smalls (future composer of The Wiz) talk about the "soul" of music and how different genres emphasize different beats. Nesmith had his segment with Zappa the following week, while the series's final episode, "The Frodis Caper," was directed by Dolenz. The show's final segment, also overseen by Dolenz, featured singer/songwriter Tim Buckley performing "Song to the Siren" unaccompanied.

Rather than carry on with a third season of the show, the group and producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider commenced work on a feature film. Envisioning it as something artsy and utterly antithetical to the version of The Monkees seen on their show, Head stands out as a boldly un-commercial film. Years later, Jones bemoaned its avant-garde qualities, saying it "should have been something like Ghostbusters," featuring the four in a ninety-minute version of the show.9 Still, Nesmith is one of the film's biggest champions, specifically its antiwar and anti-commericalism messages. It also launched Rafelson and Schneider into the Hollywood limelight, along with their cowriter, a young actor named Jack Nicholson. The three would go on from Head to work on Easy Rider the following year. Head remains an oddity, beloved by fans of underground art-house cinema and loathed by those who loved the band as they saw them on television.

Their groundbreaking work in television and one underrated film aside, there is some fantastic music in The Monkees' canon. Many of the band's releases featured tunes from some of the best pop songwriters in the business: Neil Sedaka, Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart, Gerry Goffin and Carole King, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, Carol Bayer Sager, Neil Diamond, and Harry Nilsson. However, the band did have an excellent songwriter among them in Mike Nesmith. His debut solo album, The Wichita Train Whistle Sings, is an all-instrumental showcase of Nesmith tunes rendered by a rock band and an orchestra. He later joked it was little more than a tax write-off, but the resulting album is truly one of a kind. After leaving the group in early 1970, Nesmith went on to enjoy modest success with The First National Band, standing alongside The Byrds and Neil Young & Crazy Horse in being a seminal act in the country rock scene.

The most frustrating fact about The Monkees' treatment by the hip press—even today—is their continued exclusion from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In 2007, following an incident where Rock Hall founder and Rolling Stone editor-in-chief Jann Wenner allegedly overrode votes to exclude The Dave Clark Five in order to induct Grandmaster Flash, Tork lashed out at Wenner, saying The Monkees' failure to even get on a ballot was due to "a personal whim," and that a Rolling Stone columnist had informed Tork of Wenner refusing to run an article that offered positive coverage of the group. Tork also pointed out the number of contemporary pop musicians who do not play their own instruments, and yet, "[Wenner] feels his moral judgment in 1967 and 1968 is supposed to serve in 2007."10

Tork's observation reflects just how significant the influence The Monkees has been on the pop scene, where a manufactured image is damned by serious-minded critics and listeners and simply ignored by people who "just enjoy the records," as Burdon put it forty years prior. The group remains not only a fascinating case study of how the industry seeks to maintain a hold on its stars, but also a story of four men with a remarkable (and often overlooked) talent and of their problematic brush with fame. One can only hope now that in the wake of Jones' death there will be a serious reevaluation of the group's place in the history of rock and roll.

Notes

- 1 Quoted in Eric Lefcowitz, Monkee Business: The Revolutionary Made-For-TV Band (Port Washington, NY: Retrofuture, 2011), 69–70.

- 2 Both songs can be found as bonus tracks on the CD reissue of Headquarters.

- 3 Don Kirshner quoted in Hey, Hey We're The Monkees, VHS, directed by Alan Boyd (Los Angeles: Rhino Home Video, 1997).

- 4 Lefcowitz, Monkee Business, 61.

- 5 Ibid.

- 6 Ibid., 80–81.

- 7 The author has done considerable research on Zappa's career, and no other source indicates Zappa ever made this offer, or was serious about it.

- 8 Email to author, 20 July 2010.

- 9 Davy Jones as quoted in Hey, Hey We're The Monkees.

- 10 Richard Johnson, "Monkee Lashes Out at Wenner," The New York Post online, http://www.nypost.com/p/pagesix/item_EoM175UPPYYsmgyThg9o9M, (Accessed 11 March 2012).