American Music Review

Vol. XLI, No. 1, Fall 2011

By Aaron Ziegel, University of Illinois

New recordings of music by Vernon Duke are few and far between. His two great season- and city-specific hit songs, "April in Paris" and "Autumn in New York," remain familiar standards, but full recordings of his musicals or concert works are a relative rarity. In 1999, the Chandos label issued his early ballet score Zéphyr et Flore, dating from when the composer was still Vladimir Dukelsky. Despite Gennady Rozhdestensky's insightful conducting, that disc did not remain in print for long. More recently, Naxos devoted an entire album to Duke, pairing his concertos for piano and cello as part of their "American Classics" series (released 2007). On the popular-song side of his output, Dawn Upshaw's splendid 1999 song recital from Nonesuch ably illustrated the richness of Duke's work in musical theater, mixing standards with lesser-known fare. In terms of new recordings of complete shows, however, listeners have had little from which to choose. City Center Encores! production of the Ziegfeld Follies of 1936, a collaboration between Duke and Ira Gershwin, made it into the Decca Broadway catalogue in 2001. That album was essentially the end of the story until 2011, when the enterprising PS Classics label resurrected Duke's 1946 show Sweet Bye and Bye as part of their series of new studio recordings of "forgotten musicals."

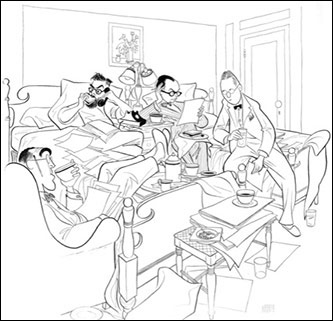

Vernon Duke and the creative team of Sweet Bye and Bye "Death in Philadelphia" (1947) by Al Hirschfeld

Sweet Bye and Bye was a flop of epic proportions—Duke called it "the noisiest and floppiest of them all"—never making it past out-of-town tryouts.1 On paper, the lineup looked good: Duke teamed up with lyricist Ogden Nash, while Al Hirschfeld—taking a detour away from cartoons and drawings—and the New Yorker humorist S.J. Perelman provided the show's book. And what a book it was. The year is 2076. The time capsule buried at the 1939 World's Fair has resurfaced (literally brought to the surface by scuba divers, since most of Long Island has been underwater following a hurricane in 2064). When scientists open the capsule, a document is discovered which gives a controlling share in the world's most profitable candy-making cartel to the heir and namesake of the company's original founder. Thus enters the musical's lead, Solomon Bundy, a Candide-like simpleton, employed as an arborist in a world with few surviving trees. Through a series of complicated twists and turns, the naïve Solomon is transformed by his love interest (the CEO-personality consultant Diana Janeway) into an arrogant business executive. He ultimately has to fight to regain his true self and to win back Diana, for she had fallen in love with the original Solomon and not the corporate clone she helped to create. The show sought to critique capitalism-gone-awry through the guise of a futuristic musical comedy.

Whether or not one thinks a convincing musical could ever have been made out of these ingredients, poor casting choices killed the project on arrival. Album producer Tommy Krasker's engaging booklet notes (generously illustrated with production and cast photos) thoroughly document a troubled history that even the composer himself left out of his otherwise tell-all autobiography. Through continuous rewrites and cuts, the book musical originally envisioned by Duke and Nash ultimately morphed into something more akin to a sketch-comedy revue, and after the expenditure of a half-million dollars, the producers finally pulled the plug.

What PS Classics has given listeners here is what may be the best possible version of Sweet Bye and Bye, with restored musical numbers that make the strongest case for Duke and Nash's score. Although the Library of Congress's Vernon Duke Collection holds file upon file of relevant musical materials, no original orchestrations survive. Producer Krasker turned to orchestrator Jason Carr, familiar to Broadway audiences from his recent work on revivals of Sunday in the Park with George, A Little Night Music, and La Cage aux Folles. Here Carr writes for an eleven-piece combo, conducted by Eric Stern. This small ensemble produces a pleasantly full sound and delivers some superb solos, but the overall effect at times comes across as much too contemporary, belying the score's mid-1940s origin. The choral arrangements, on the other hand, are primarily Duke's own and are enthusiastically delivered by a chorus of sixteen voices, particularly in the show's title song that opens the album. The recording includes a certain amount of spoken dialogue—perhaps more than some listeners would like— but enough to help clarify plot points that the musical numbers themselves do not. The booklet helpfully includes the complete sung lyrics, all the better to ap- preciate Ogden Nash's subtle wit and inventive rhymes.

The real reason to own this album, however, is for the songs. Sweet Bye and Bye includes some of the composer's most complex theater writing, the type of work that led Alec Wilder to describe Duke as "a true innovator in the world of the sophisticated love song."2 Chief among them are "Born Too Late" and "Roundabout," both expertly sung by Philip Chaffin as Solomon Bundy. Chaffin delivers Duke's treacherous vocal melodies with aplomb. He captures just the right tone of innocence and loneliness in "Born Too Late," as Solomon explains how out of place he feels among late twenty-first-century technology and society, while "Roundabout" takes on new meaning in its original context. Duke reintroduced the song in 1952, with altered lyrics, in the show Two's Company, where it became the plaint of a lovelorn woman. Originally, however, the song gave Solomon the opportunity to vent his bitter disappointment at how his transformation into an industrial tycoon has still left him unhappy and unfulfilled. Chaffin rises to the occasion admirably, delivering a poignant and agonized reading of the Act One finale, the score's musical highpoint.

The remaining lead players inhabit their roles just as convincingly. Like Chaffin, Marin Mazzie (as Diana Janeway) explores a broad dramatic range. She first appears as a controlling corporate vixen in "Diana," softens for the show's only romantic duet, "Too Enchanting," and longs nostalgically for her lost love in "Just Like a Man." Danny Burstein performs the comedic role of Egon Pope, the blustery general manager of the Futurosy candy company, with a high level of enthusiasm but in a speech-song patter that might not be to everyone's taste. The large supporting cast, despite maintaining the overall high level of performance, points up the show's principal weakness. The plot is simply too episodic, with characters introduced and then abandoned after only a single scene or a single song. A pair of Futurosy company secretaries, out-of-work CEO-types at an "Executives Anonymous" meeting, a tramp riding the cargo holds of interplanetary space liners like a railroad hobo, and an Eskimo princess who tries to seduce Solomon—each receives a musical number, and indeed their songs are often quite good. But the unifying thread of Solomon and Diana's romance gets all too easily lost amongst the surrounding bustle of plot activity.3

Ultimately, Sweet Bye and Bye as a piece of theater is no lost masterpiece, and yet we are fortunate that its zany plot inspired such high quality songwriting from Duke and Nash. Given that Duke's compositional language is primarily one that rewards a listener's close scrutiny rather than one of immediate appeal, a work like this is perhaps better served on record than on stage. The composer himself concluded that the show's futuristic, "cockeyed and wildly phantasmagorical libretto" met with disfavor because, "following the horrors of war and the atomic bomb, nobody was in the mood to look ahead, the prospects being as bleak as they were."4 Album producer Tommy Krasker, however, remarks in his accompanying essay that the show's central theme—"how do you find your way in a world that seems to be constantly changing?"—is "especially apt in our ever-changing cyber-universe." One can hope that the painstaking restoration work and committed performances heard on this CD will help Sweet Bye and Bye to reach a more welcoming listening public than the show first did in 1946. Now if only Krasker could be persuaded to revisit the Duke canon and revive a former winner. Surely Duke's most successful musical, Cabin in the Sky, is long overdue for rescue and rediscovery.

Notes

- 1 Vernon Duke, Passport to Paris (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1958), 434.

- 2 Wilder here is referring specifically to "Born Too Late." See his American Popular Song: The Great Innovators, 1900–1950 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), 368.

- 3 Curiously, the images on the booklet cover and jewel case inlay depict a pair of robots working an assembly line conveyor—characters in a substitute song written by Duke and Nash but not included on the present recording.

- 4 Duke, Passport to Paris, 434.