American Music Review

Vol. XLI, No. 1, Fall 2011

By Stephanie Jensen-Moulton, Brooklyn College

A few minutes after the curtain closed on the 17 September 2011 performance of Gershwin's Porgy and Bess, the dramaturge beckoned interested audience members to the center seats in the front of Cambridge's Loeb Theater for a question and answer session with the cast. One of the first questions came from a woman in the back of the theater: "Why did you take away Porgy's goat cart? It's such a poignant moment in the opera, seeing him riding off to New York after Bess." Her words encapsulate a host of largely unexplored questions about the male lead in this iconic American work of music theater. While scholars and critics alike have focused primarily on issues of race and gender in Gershwin's opera, Porgy's disability, and its seeming incongruity with a violent love affair, was the germ that led Dubose Heyward to write his novel Porgy in the first place. So much happens in Porgy and Bess—a murder, a sexual assault, drug dealing, police brutality, a hurricane—that discussion of the opera's mediation of disability often falls by the wayside. The new production of Gershwin's piece by the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) has already ignited heated arguments about genre and authenticity, and the decision to equip Porgy (played by Norm Lewis) with a cane instead of a cart is but one of many changes in this new version of the drama. But unlike the 1993 BBC production of the opera, in which Porgy also used a cane, the characterization of Porgy in the A.R.T. production has shifted in accordance with the prosthetic he employs. Norm Lewis's Porgy transforms before our very eyes from a stooped, limping beggar with dirt on his clothes to an upright and active romantic hero, ready to fight for his woman.

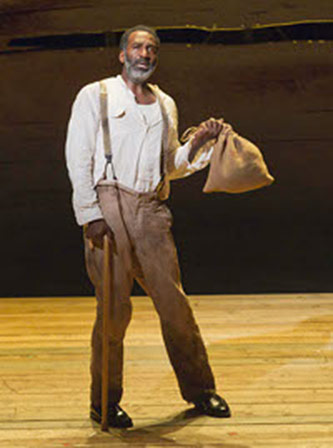

Norm Lewis as Porgy, Photo by Michael J. Lutch, courtesy of the American Repertory Theater

From the opening song of the production, Clara's "Summertime" lullaby sung in a lowered key to a real baby, it's clear the creative team of director Diane Paulus and playwright Suzan-Lori Parks had authenticity on their minds. According to Parks, the opera needed to be rewritten not because it was racist, but rather because it had some confusing moments and some gaping dramatic holes. She writes: "Now, one could see [Heyward and Gershwin's] depiction of African-American culture as racist, or one could see it as I see it: as a problem of dramaturgy.... I allowed myself to see Porgy and Bess as a piece of writing that, while not morally flawed, very much needed to be fleshed out."1 Parks sought out situations in the dramatic structure of the piece that simply did not work well, or that presented dated stereotypes or one-dimensional stock characters. Then, by having the characters more clearly defined, she made sense of each encounter or problem. In addition, the use of dialogue in lieu of recitative lets the motivation for each scene become clearer and more "organic," a buzz word for this production. As Paulus and Parks worked with Norm Lewis to create a Porgy that would fit with the style and depth of their concept, the mediation of his disability became primary to the re-envisioning of this role. While previous incarnations of Porgy have remained static in terms of their status as disabled, Norm Lewis plays a Porgy who dreams of being cured of his affliction. Though he identifies as a "cripple" in the piece, he does not intend to remain one. As my colleague Ray Allen states in the accompanying review, "This Porgy is more than a tragic cripple who happened upon an unlikely summer romance—here is a man driven to overcome his disability, to satisfy his lover, and to live life to its fullest." While Allen's statement reflects the reality of the production's dramatic arc for Porgy, it draws a predictable and somewhat oversimplified line between disability and cure that presumes that all differences—physical or cognitive—must be normalized or eradicated. The A.R.T. incarnation of this character might be viewed as an allegory for the way disability tends to manifest itself on the American operatic stage: as a contradictory bundle of stereotypes, good intentions, and intensely studied performances by able-bodied singers.

Norm Lewis begins his performance of Porgy with a makeshift cane, a knotty stick with a bulbous end covered in a greying handkerchief. His pants are filthy from occasionally pulling himself along on the ground—in fact, he is the only character with any literal dirt on his clothing—and his shoes are misshapen from the dragging of his left leg. He must bend at the waist to accommodate a hip that will not turn when he walks. Porgy's is the only visibly disabled body on the stage, and the decision to give Porgy a cane rather than the traditional goat cart complicates the character's identity as previously understood. In DuBose Heyward's novel, the basis for the opera, Porgy's acquisition of the goat cart is literally a godsend, enabling him to reach his preferred locations for pan-handling without the help of his friend, Peter, who rents a horse and cart. As the novel progresses, Porgy is able to travel all over Charleston to perform various errands on his friends' behalves, all due to the helpmeet of his goat and cart. Nothing is desired or imagined beyond the convenience and independence this conveyance has provided for Porgy. And in the original 1935 opera, once ensconced in his cart, Porgy can carry himself smoothly—though often somewhat comically—about the stage, enabling the audience to forget that Porgy might need or want another way of getting around. In the question and answer session, Norm Lewis noted that the cane has given Porgy strength, while the cart rendered him weak. He also referenced the design team's needs, stating that a cart "would not work on this type of stage," which, with its raised platform, would have been inaccessible to cart (if not goat).

But Porgy with a cane changes everything, complicating the very notion of desire in the piece. From the first moment of his entrance, we see Norm Lewis's Porgy struggling, dragging, limping, falling. Of course we want him to find a better way to get around, and we are glad to hear in this new production that Porgy is saving up for a leg brace and a new cane. Not only do these medical accoutrements legitimize Porgy's mendicancy and gambling (because now these habits might be viewed as the means to a righteous end), but they also give him the powerful air of a man who has taken charge of his life through untold resources of inner strength. Porgy tells Bess that "God gives cripples an understanding of many things he don't give strong men." This is the American fable of disability writ large: that those with "feeble" bodies must have compensatory powers of will, and even, in Porgy's case, supernatural understanding.

Porgy's cane also enables him to envision a life in which someone else can depend on him, rather than realizing the trope of a dependent disabled person. Porgy even sings that Bess "must laugh and sing and dance for two," implying that he can do none of these things. However, the emasculated Porgy of the opera who must count on a woman for everything is annulled in several ways in the A.R.T. production. Although Porgy acknowledges that as a "cripple from birth, God made me lonely," he also refers to his desire to become a "natural man" throughout the dialogue. The opposition between Porgy's disability and what is "natural" in a man—implied here as being able to run, work, drink, dance, love—sets up Porgy's ambition to acquire whatever is needed to rid himself of the issues caused by what Heyward described as his "totally inadequate nether extremities."2 Problem by problem, this production addresses all of Porgy's "inadequacies," resulting in a Porgy whose limp turns to a swagger by the end of the piece.

Primary among these dramatic problems is Porgy's relationship with Bess, which begins early in Act I. When Crown, Bess's immense stevedore, becomes angry with Porgy for winning at craps, a fight breaks out. Crown does not even consider wrestling with Porgy, but demands that "someone else take the fight for Pops." Robbins steps forward, and Porgy's perceived inability to fight effectively results in Crown committing murder. The moniker "Pops" when applied to Porgy is doubly inaccurate: he is neither a father nor elderly. But, as disability advocate Christopher Baswell states, "words like ‘Pops' create a torque of identity, twisting and untwisting as they create meaning."3 Though Norm Lewis sports a graying beard in the show, it is primarily his character's way of moving through the physical world that causes the misperception of Porgy's advancing age.

The other half of the "Pops" equation is the implication of fatherhood, which obliquely references male heterosexuality. Along with Porgy's obvious physical differences come a host of assumed malfunctions, up to and including sexual dysfunction. While in most stagings of Porgy and Bess the leading lady's choice to stay with Porgy instead of Crown serves as an allegory for her choice of chastity and a God-fearing life over one of sex and addiction, the A.R.T. production does not fall into the easy and common assumption that disabled individuals are in essence asexual. Parks re-envisions Porgy's song "I Got Plenty of Nothing," playing on the modern sexual slang of "getting somethin'" from a woman or man. After being together with Bess for several days, Porgy's friends in Catfish Row notice his change in manner and shy happiness, and ask, "Hey, look at that smile you got, what you been up to?" Porgy smiles widely and responds somewhat mysteriously: "Nothin'... ." When he smiles even more broadly, they all laugh knowingly, and it's clear Porgy has been having "plenty" of Bess. As Allen notes, the song transforms from a "naïve embrace of poverty" into an allegory for Porgy and Bess's sexual relationship. This reconsideration of a beloved song is powerful on multiple levels, calling into question not only assumptions about disability and sexuality, but also about Porgy's identity as a black man. When his asexuality is assumed, so too are his weakness and harmlessness. But the assignment of virility to Porgy's character both dismantles misperceptions about his age and sexuality and makes more realistic his capacity to kill Crown later in the show.

Crown serves as a foil to Porgy throughout the piece. But unlike other productions of the opera, the A.R.T. version allows Crown his share of human weakness, just as it opens the door for Porgy's cure and "re-masculation." Though both Bess and Crown appear to be physically powerful, their addictions disable them, resulting in exile (Crown) and ostracism (Bess, before Porgy). Bess is also disfigured; a scar on her left cheek stands as evidence of her wild past as a "yaller gal" who used happy dust and ran with Crown's crew of heavy drinkers and gamblers. After being with Crown for more than five years, Bess finds herself indebted to Porgy for saving her from the police after Crown murders Robbins. She is high, drunk, and doesn't know how to speak to him, saying, "Look at me, you damn dummy." Before getting to know him, Bess assumes that Porgy is not only physically but also cognitively disabled. Later, when Bess encounters Crown on Kittiwah Island and he learns that she wants to stay with Porgy, he grunts, "You sho' got funny taste in men," limping across the stage in imitation of Porgy's gait, implying that to limp is to be less than a man. But Porgy himself seems to agree, given that he persists in assuring Bess that he will be a "real man" and a "natural man" once his new cane and brace begin to do their work. Late in the drama, when Crown returns from the island to meet his fate, Porgy is able to stand without his cane, wrestle Crown to the ground, and murder him.

Even after this act of violence and struggle, Porgy cannot keep Bess. During Porgy's stint in prison, Sportin' Life returns to Catfish Row, peddling happy dust and trying to lure Bess to New York. He draws a distinction in the dialogue between "your kind" (Bess, a gal who can live fast and loose) and "his kind" (Porgy, a cripple). In this production, Sportin' Life's final gesture in the attempt to convince Bess is yet another mocking of Porgy's limp, this time performed by David Allen Grier with a stylized jauntiness becoming his identity as a spat-sporting dandy. It is this gesture that seems to operate on Bess at the deepest level, and although she refuses the happy dust, she does follow him to the big city. By the final number, however, Porgy's limp is barely perceptible as he turns his back to the audience on his way to New York in search of Bess. The narrative cycle is completed as Norm Lewis runs onstage in Porgy's leg brace, cured by curtain call.

Notes

- 1 Suzan-Lori Parks, Interviewed by Jared Bowen in "New Interpretation of Porgy and Bess Provokes as it Continues to Resonate," authorized clip from PBS Newshour 26 September 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wr_D6J1VocU (accessed 30 October 2011).

- 2 DuBose Heyward, Porgy (Dunwoody, GA: Berg Publishers, 1925), 12.

- 3 Professor of English, Christopher Baswell, as part of a panel discussion entitled "Disabled at Columbia" held on 6 October 2011, related his experience of being stranded in a corridor between two locked doors as he attempted wheelchair access to spaces at Columbia. When a student found him, the student asked, "Need help, Pops?" Baswell related that he had never before been addressed with that monicker, and that it caused him to ponder the nature of disabled identity, and how it can be twisted by the spaces we inhabit. If he had been at the front of a classroom, the term "Pops" would not have been applied to him.