American Music Review

Vol. XLI, No. 1, Fall 2011

By William Bares, University of North Carolina, Asheville

I imagine some readers may be curious about the title of this article. How relevant could geographically and culturally remote Norwegian jazz be to a publication devoted to American music? Some readers may associate ideas of "North" and "silence" in music with people closer to home: Glenn Gould, or John Cage––or even Simon and Garfunkel.

Jazz aficionados, however, will more likely associate these themes with the music of Europe's Editions of Contemporary Music or "ECM" label. Virtually all of ECM's high-reverb, high-fidelity, low-activity jazz records have been produced by owner Manfred Eicher, and most have been engineered by wizard Jan-Erik Kongshaug at his famous Rainbow Studios in Oslo, a place mythologized for its light, space, and acoustics that inspire introspective ways of playing. As early as 1971, the ECM sound was being hailed by publications like Canada's Coda magazine as "the most beautiful sound next to silence"1––a phrase that for many perfectly encapsulates ECM's emphasis on minimalist, ambient, and self-consciously artistic jazz productions.

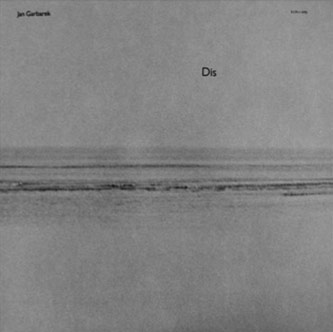

These productions are further aestheticized, in a way, by graphic designer Barbara Wojirsch's famously austere landscape cover art. The packaging has lent itself to what Eicher has called "a certain kind of personality in our work... something that speaks to you in the image, usually things that are enigmatic, or dry, or weird, dark or cold, images that go well with the music."2 For partisans on both sides of the Atlantic, ECM productions can and have been seen variously as distinctly European or Euro-American; anti-modern or ultra-modernist; anti-commercial or the gold standard of slick jazz marketing. For some, the music amounts to aural wallpaper. For others it whispers an invitation to listen more closely.

Cover of Jan Garbarek's Dis (1973), ECM Records, Design by Barbara Wojirsch

My goal is not to pronounce judgment on the ECM sound but rather to assess its legacy and impact in three concentrically related contemporary cultural spheres that I call the Norwegian, the European, and the transatlantic. In each of these contexts, the politics and poetics of jazz "silence" have served as bulwarks against a perceived hegemony of American jazz. The question, however, is to what degree the investment in this "silence" erects a new kind of hegemony with its own political problems. What silence "signifies" in the national Norwegian context may be quite different from what it signifies in the European context, and yet again in that of the transatlantic.

Of course, the "silence" aesthetic is hardly the exclusive property of Norwegians, or even Northern Europeans. As jazz scholar David Ake has shown in a recent Jazz Perspectives article on the "rural" ideal in American jazz, ECM's American artists Keith Jarrett and Pat Metheny were no less important to the development of a similar style of jazz playing in the U.S. (e.g., Jarrett's "Country" fromMy Song or Metheny's "(Cross the) Heartland" from American Garage).3 In his article on cool jazz for theOxford Companion to Jazz, historian Ted Gioia called ECM the "clear heir" to the cool jazz tradition, noting that although the sound would never be confused with that of Miles Davis, Gerry Mulligan, or Stan Getz, its valueswere essentially the same: "clarity of expression, subtlety of meaning, a willingness to depart from the standard rhythms of hot jazz and learn from other styles of music; a preference for emotion rather than mere emoting; progressive ambitions and a tendency to experiment; above all, a dislike for bombast."4

As a member of ECM's inner circle––having played bass in the Norwegian groups of saxophonist Jan Garbarek, guitarist Terje Rypdal, the superband Masqualero, and well as his own groups—Arild Anderson is a prominent exponent of cool jazz values, though he is more apt to associate them with a Nordic sensibility. As he recently explained to journalist Stuart Nicholson, in Norwegian jazz, "the sound is very important, the space in the music is very important, the transparency is important, the dynamic is important, not how clever you play your instrument, how fast you can play or how impressive you could be but how expressive you are."5 If the style is defined negatively here against American jazz virtuosity, Anderson's statement is equally notable for enumerating a set of positive musical values that align perfectly with a more broadly defined Norwegian politics and poetics.

The poetics of Norwegian art have traditionally evoked evasive concepts of depth, landscape, interiority, or solitude. One thinks here of Munch's famous expressionist painting, The Scream, depicting existential despair on a promenade in front of Oslo Fjord. Or Grieg, and his use of open fifths to convey a sense of the vast chasms that define much of the Norwegian landscape. As journalist Michael Tucker notes in Jan Garbarek: Deep Song(Hull, 1998), by the mid-1970s Norway's ECM artists had begun to align their musical productions with these age-old Norwegian artistic tropes. Garbarek's album, Dis (meaning "fog" or "mist") can be seen as a pivotal album in this development. Here the Norwegian landscape is not figuratively evoked but rather actually used, as Kongshaug's recording of a specially made wind harp placed on a beach in southern Norway becomes the third, equal member of Garbarek's trio. On the provocatively titled thirteen-minute track "Wanderers" we hear Garbarek conversing in plaintive, icy tones with the North Sea wind, which produces open fifths and overtones in E major on the harp.

In my years of field research on European jazz from 2006–08, I encountered many contemporary variations on this theme. Singer Solveig Slettahjell's performance at Jazz Baltica with her aptly titled "Slow Motion Quintet" transfixed the north German audience with icy tones and pensive beats. The carefully manicured grunginess of the sidemen and their use of imported American retro instruments, including the autoharp for rural connotations, reinforced the pastoral mystique. Another famed Norwegian group, Supersilent, showcased world famous trumpeter Arve Henriksen, who manages to make the trumpet sound like a Japanese shakuhachi flute, and Helge Sten, a.k.a. "Deathprod"—whose trademark audio "virus" effect involves manipulating sounds in real-time to produce a stark sonic backdrop for the group's improvisations.

In Julian Benedikt's documentary film, Play Your Own Thing, the Story of Jazz in Europe (2007), Garbarek defended sparse Norwegian jazz conceptions, noting that

Nobody can play like Charlie Parker, ever, and there are so many hundreds of thousands of people who tried...to live their life like him and to try to play his phrases and do it as freely and quickly and impressively as he does, but there's no chance. Every day you hear people who are intimidating you, certainly, and there are players you look up to and you will never have the facility that they have. But still, you know you have something else. [...] It's not difficult when you have no choice, really. It's very easy, in fact, in that sense, when that's the only way you can play.

In what may seem to some like a cop-out, Garbarek makes a play here for a kind of jazz egalitarianism (an emphasis on playing what comes natu- rally) which, considered alongside his influential "nature-evoking" sound, resonates with the strongest values in Norwegian political culture. The famous photo of King Olav the Fifth, taken in an Oslo subway in 1973, at the height of the oil crisis, illustrates what many have cited as the three pillars of Norwegian political identity: Egalitarianism, Moderation, and Closeness to Nature. He is seen traveling with ordinary people and wants to pay for his own ticket (equality). He sports an old, worn-out jacket (moderation) and he is on his way to a nearby skiing area (nearness to nature).

Norway's King Olav V, 1973

That the Norwegian King himself would embrace this culture of moderation and egalitarianism speaks to the ease with which the silent, non-hierarchical and non-showy jazz conception promoted by Garbarek and ECM has taken root in Norway. This Norwegian sound continues to be viewed, quite positively, as resounding with widely shared Norwegian values. On the other hand, its very association with these values means that it can also be seen, negatively, as restricting individual impulses to sound different within Norway. As many musicians have told me, jazz funding structures, which are abundant in Norway and which strive to be egalitarian, nevertheless tend to reward disproportionately those musicians who adopt this readily identifiable Norwegian silence aesthetic. They are deemed more likely to be successful abroad, and less likely to disturb the peace at home.

This self-perpetuating cycle, incidentally, aligns with Danish-Norwegian author Aksel Sandemose's infamous "Jante Law" (Janteloven), the ironic credo of elder-dominated communal living that remains a cornerstone of the Norwegian self-image. According to Scandinavian music scholar David Kaminsky, the ten prohibitions can be boiled down to the dictum: "Don't think you're anyone special or that you're better than us." In Norwegian jazz, the dictum can generate considerable social cohesion, but can also tacitly enforce a silence that may seem inadequate for addressing the contradictory elements in Norwegian society, such as the rub between the rich oil-based economy that allows the country to remain cutting-edge and modern and its core values of environmentalism and egalitarianism.

Although virtually all of my younger Norwegian informants understood what I meant when I asked them directly about the role of silence in their playing, few, if any, wanted to be identified exclusively with this jazz sound, suggesting that there are real social issues in Norway for which musical silence does not provide all the answers. As I discovered, many Norwegian jazz musicians still find the "bombastic" American jazz sound quite useful for differentiating themselves, projecting irreverence, or ruffling feathers in the Norwegian context. One such musician is pianist Anders Aarum. In 2004, Aarum secured money from both the Norwegian government and his label, Jazzway Records, to record a silent-themed album at Rainbow Studios in Oslo. According to Aarum, Rainbow's exquisite sound and cavernous environment inspired him and his trio to play "less" and listen "more." The result was the aptly titled album Absence in Mind. In 2007, however, Aarum surprised everyone by earning a Norwegian Grammy nomination for the album F.A.Q., which featured remarkably busy and American jazz-savvy music, including his send up of the standard, "My Heart Belongs to Daddy," humorously entitled, "My Hart Belongs to Rodgers."

Such versatile musicianship is now highly prized in Norway. It can be read as projecting a respect for Norwegian mores and a coevality with modern American jazz. As Norwegians have discovered, the "silence" aesthetic need not be all-encompassing but can be used selectively to assert identification with contemporary Norwegian, European, and transatlantic political concerns. The 2005 ECM album The Ground, by the most internationally successful Norwegian band of recent years, the Tord Gustavsen Trio (billed as the world's "quietest" piano trio), is exemplary for addressing all three; it emerged at a pivotal historical moment for Norway, Europe, and transatlantic relations.

2005 marked the Norwegian centennial of its independence from Sweden. Gustavsen's album sold over 20,000 units in Norway that year while climbing to number one on the Norwegian pop charts, suggesting that the recording successfully tapped into that year's swell of national pride. The title track, "The Ground," exhibits what jazz critic Bill Shoemaker calls the trio's "reverent, hymn-like themes, rendered with a soft-spoken intensity, often at a glacial tempo."6 Gustavsen emphasizes that his trio's silence aesthetic is grounded in Norwegian poetic and political values—what Gustavsen calls "scenic consciousness"––defined as "an approach that bypasses the conventions of music to make it a transcendent experience... to encounter the phrases as a landscape." In Gustavsen's musicology dissertation, The Dialectical Erotism of Improvisation, he draws parallels between "the universe of improvisation and the challenges facing us in relationships. It's important to be able to feel each others' intentions."7

Not surprisingly, such sentiment was particularly well-received in the rest of Europe in 2005, during the high tide of resentment toward the Bush administration's foreign policy. It is safe to say that for many Europeans, the Gustavsen trio, unveiled on the European festival and club circuit that year, modeled an appealingly different, cooperative, nonaggressive, non-competitive European vision for jazz.

Positive assessments of the trio's like-mindedness and egalitarianism throughout Europe must be seen in the context of an emerging European jazz network of reciprocal relationships that values distinctive group sounds over individual achievement. For example, at the European jazz competition held at the North Sea Jazz Festival each year, the awards now go to groups, not individuals. The development of such infrastructures must in turn be viewed as inseparable from the cooperative European model that sees the success of any one country or region as elevating the others. Political scientist Robert Kagan famously observed that the "multinational model–– multilateralism as the weapon of the weak against the strong––has become Europe's model for global relationships."8

This brings us to the resonance of Europe-identified sounds of silence in the transatlantic cultural-political sphere. Along with Sweden's famed piano trio E.S.T., Gustavsen's jazz group was celebrated throughout Europe in 2005 for breaking into the notoriously hostile American market. Here was a group that seemingly could embody European cooperative values while alerting Americans to their own political and artistic tone-deafness. By 2005, international jazz fans began to draw connections between Bush's unilateral foreign policies and the exclusionary narratives of jazz's "American-" or "African American-ness" emanating from places like Jazz at Lincoln Center. Not all Americans got the message. The Nation's David Yaffe called Gustavsen's concert in New York's Merkin Hall "an exceptional snooze."9 For jazz pianist Fred Hersch, the group was a bad imitation of the Keith Jarrett Trio. Will Layman of popmatters.com spoke for many when he complained that "little of it feels dramatic––no tension, no narrative drive. The deliberate slowness ... makes it hard to hear the melodic movement as a connected line of music. Rather, each chord sits alone in your ear. Each one is gorgeous but ... so what? Maybe I'm missing the point. Maybe this is some kind of Norwegian make-out music. Maybe its sensuality and subtle differentiation is lost on a kid from New Jersey who used to date girls with big hair."10

The fact is, however, that the album did extremely well in America, and has sold over 100,000 units worldwide. Gustavsen's musical messages would seem to have resonated not only with Europeans but with Americans who, to quote one American fan of Gustavsen, "need a respite from the frenzy." Another American who raved about the album on Amazon.com gave the album five stars, four for the music and one for the silence. All About Jazz's Elena Gillespie hinted at the symbolic role European "silent" jazz sounds plays for many Americans, noting that they "tell all the stories that belong to us. No grandstanding, metaphorical flag-waving, or ‘Look Ma, no hands!' here. The moments that get washed away all too easily in the face of a culture that constantly screams that more is never enough are what this music addresses."11

But there is something else that gets washed away all too easily here. 2005 was also the year of Hurricane Katrina, whose aftermath had confirmed for much of the world that America remains a radically inegalitarian society more concerned with capital accumulation than its own cultural treasures, like the living New Orleans jazz archive that was literally washed away that year. If Gustavsen's jazz populism can be taken for a well-orchestrated European musical form of anti-American protest, it must also be seen as no great news to African American jazz communities for whom jazz has long protested against precisely this inegalitarianism. Given the successes of Gustavsen's The Ground, then, as a kind of internationally resonant political statement, the year 2005, it seems to me, demonstrates just how easily African American jazz protest––manifest in, among other things, an often loud, insistent, and virtuosic music––can be conflated with American imperialism overseas and therefore ignored in favor of the silent European variety.

The patterns of global jazz "traffic" are complex, offering possibilities and pitfalls, clear winners, and losers. On the one hand, we might celebrate the fact that the contemporary world allows Norwegians to use American jazz individualism to break through the strictures of Jante Law, while allowing others to use Norwegian jazz silence as an antidote to American fascination with musical, military, and economic prowess. On the other hand it is clear that age-old conflicts between black and white jazz communities in the U.S. over scarce resources, audiences, and recognition are now complicated by a transatlantic context whose economic inequalities are becoming more and more apparent.

Coming from a Scandinavian jazz musician whose powerful backers included the Norwegian government, ECM records, Kongshaug, and influential journalist Stuart Nicholson, Gustavsen's emphasis on silence and listening may disguise a distinctively Scandinavian luxury, defending a conception of jazz as the province of a relatively privileged few who needn't have anything at all to "say," individually, in order to be "heard" together. Most of the African American artists with whom I spoke were painfully aware that such groups now provide popular alternatives to their own challenging historical dialogism, rhythmic subterfuges, timbral contrasts, and soulful complexities. They sense that fewer and fewer in Europe have the ears to listen for these things.

The doors open to people like Gustavsen may remind many of certain historical patterns associated with white European and Euro-American privilege. It may, after all, seem like a kind of white privilege to romanticize the land, which relatively few African Americans own. It can seem like a kind of white privilege to romanticize "naturalness," when African Americans have long used jazz to protest against the very idea of the primitive "natural" musician. Finally, it may seem like a kind of white privilege to romanticize silence, when it has, and continues to be, forced upon African Americans by more powerful constituencies.

Notes

- 1 Steve Lake and Paul Griffiths, Horizons Touched: The Music of ECM (London: Granta Books, 2007), 188.

- 2 In Adrian Shaughnessy, "Think of Your Ears as Your Eyes," http://www.eyemagazine. com/feature.php?id=47&fid=299 (accessed 5 November 2011).

- 3 David Ake, "The Emergence of the Rural Ideal in American Jazz: Keith Jarrett and Pat Metheny on ECM Records," Jazz Perspectives 1, no. 1 (January 2007): 29–59.

- 4 Ted Gioia, "Cool Jazz and West Coast Jazz," The Oxford Companion to Jazz (New York: Oxford, 2000), 342.

- 5 In Stuart Nicholson, Is Jazz Dead? (Or has it Moved to a New Address) (New York: Routledge, 2007), 103.

- 6 Gustavsen as quoted in Robert Siegel, Jazz Pianist Tord Gustavsen Plays on his own ‘Ground,'http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4682800 (accessed 5 November 2011).

- 7 Ibid.

- 8 Mark Leonard, Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century (London: Fourth Estate, 2005).

- 9 David Yaffe, "Soul on Ice," The Nation (5 December 2005): 47.

- 10 Will Layman, "Tord Gustavsen, The Ground," http://www.popmatters.com/pm/re- view/gustavsentod-ground (accessed 5 November 2011).

- 11 Elena Gillespie, "ISO E.S.T.," http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/article.php?id=15540 (accessed 5 Nov 2011).