American Music Review

Vol. LI, Issue 1, Fall 2021

By Stephanie Jensen-Moulton

On a stormy Saturday in November, I carried my laptop to the basement to record an interview with music scholar and prolific writer Alejandro L. Madrid, whose recent biography on composer Tania León was published in late 2021 (University of Illinois Press). The unexpected tornado warning and electric skies provided a dramatic backdrop for the conversation about our mutual colleague, and on the practice of writing about living public figures, individuals whom we admire, and who share in the reading and editing of their own biographies.1

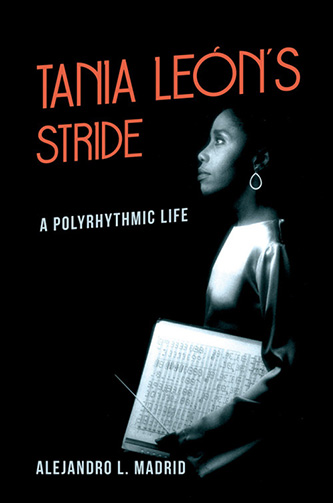

SJM: I’m here [on Zoom] recording a conversation with Alejandro L. Madrid, the author of Tania León’s Stride: A Polyrhythmic Life. So when did you first think about writing on Tania León and had you known her personally before you began this project?

ALM: That’s an interesting question. I wrote about her for my book on danzón, the book that Robin Moore and I wrote.2 The last chapter deals with reinventions of the danzón in contemporary settings and by concert composers who are not necessarily thinking about dance. And you know, the danzón is something that appears very often in Tania’s music. We analyzed one piece by Tania in that book, and we actually had some conversations back then to ask her how she was incorporating the danzón in that piece. So, I did an analysis in which I was trying to trace the quotations of the danzón [“Almendra” by Abelardo Valdés] and she liked it a lot, apparently. That’s how we met. And then years later, in 2016 or 17—it was the 50th anniversary of her arrival in the United States—she started looking for someone to write her biography. She told me that she approached Walter Clark from UC-Riverside, and Walter told her that I might be a good person to ask. Tania reached out to me and asked [if I was interested in writing the book]. I very hesitantly agreed to take on the project, because I had just written this book called In Search of Julián Carrillo and Sonido 13 (Oxford, 2015), which I sort of conceptualized as an anti-biography.

SJM: That probably made her like you even more!

ALM: Maybe! [laughs] Maybe. But yeah, we discussed the idea and it was clear that she did not want just an uncritical hagiography, right? And once it became clear that I would maintain some sort of independent agency, I decided to take on the project. There was also a commission that came from Brandon Fradd.3 He paid for everything, basically for me doing the research—my trips to Cuba to interview her relatives and her friends and my trips to New York to interview her and other people and attend events that she was involved with—all of that was paid for by this commission.

SJM: That’s really helpful, and it kind of leads me to another question, and, in a way, answers it. I was wondering how you decided to divide up the chapters because the form of the book is very unconventional for a biography. I’m guessing it has to do with your anti-biography project? I find it both feminist and non-positivist, and I wonder if you can illuminate this a bit more in relationship to your previous project.

ALM: Yeah, that’s for sure. The very first thing that I wanted to do was to break away from a chronological narrative. I had this idea that I was going to take musical motifs from her music, and relate them to things that were important in her life; like the idea of tonic as home, you know, the home that she had to leave, and then make a new home in a new country. Then displacement and syncopation as again this idea of having to leave and having to incorporate the rhythms of a new life in a new place. That gave me a good reason to explore the relationship that she has with different Afro-American initiatives and cultural projects that she has been involved with. As you know, she really had to negotiate [a lot in that scene] because she was perceived as Black, but once she opened her mouth she was no longer perceived as Black. So for her, it was very difficult to deal with both how she was seen and how she saw herself differently from what people expected from her.

Then I thought about the idea of the conductor as a leader—not only as leading an orchestra, but leading in life! Leading her mentees and her colleagues and opening paths for people to flourish, right? So that metaphor of conductor as a life leader and mentor was conducive to organizing the book.

SJM: Absolutely. And I think those metaphors are really telling of the way that you perceived her life as a series of important events and as connective in many ways. I thought this was a very unconventional way to write a biography that I could appreciate...

ALM: But I also want to tell you something about my first idea, which was to organize all of these different motives around the same moment, when Tania was invited to conduct the National Symphony Orchestra in Cuba. I wanted to take that moment as a vignette to start all of these different chapters, and then branch out into different directions. There were descriptions of that moment that were based on many different perspectives. One description was what the newspapers in Cuba were telling us about that concert; another perspective was how her family was looking at the concert; another, how audiences were looking at her coming on stage. It was a very cinematic idea. But Tania was very against it. She liked the general idea, but she didn’t want that particular moment to be so central in her story. She said, basically, ‘You are giving too much agency to the Cuban government and that particular invitation. And I don’t want this to be about that moment.’

SJM: I can imagine Tania disliking that as an axis for her life view because the 2016 visit to Cuba was a sensitive and difficult time.

ALM: That’s a good example of the type of negotiations that we had to do, because I really liked the idea and I still think that maybe with a different vignette it could have worked very well. But after hours and hours of conversations with her, about her relationship with the island and the regime and people who stayed behind, I understood; and I said to myself, ‘She is definitely right.’ But I held on to the general idea, because I still liked it.

SJM: Yeah. I almost feel like if Tania had won the Pulitzer a couple of years earlier, that would’ve been the perfect moment, because it’s very positive.

ALM: And, you know, there’s also that she wrote that composition for the New York Philharmonic, and then it ended up winning the Pulitzer Prize. And I was aware that this moment of going back to the New York Philharmonic after what happened [with her and that organization] in the 1990s was in itself sort of a metaphor of her life—of doing all these things and not being recognized; and then finally, thirty years later, people coming back and asking her to be on the [orchestra’s] board and all of that. So yeah. The timing was a little bit off [laughs].

SJM: And so ironic, too, that Tania’s so against the identity issue of being recognized only as a woman composer and it was a commission for the Project 19.

ALM: Her response to that was actually very telling, no? Because I asked her, ‘So what’s up with this, it’s a project about female composers?’ And she said, ‘Well, it’s about reparations.’ And to me, it seemed like it was a very personal thing [related to] all that she went through with the New York Philharmonic in the 1990s.

SJM: Absolutely. Yeah. That’s fascinating. So, with a living author, where you’re deeply involved in learning their life, how did it go when she finally read the manuscript?

ALM: I gave her the manuscript when I finished it about two years ago. And she had it almost for a year before she actually read it. I think she felt that it was too close [to her]. She felt somehow that it [dealt with] very sensitive [issues], so she didn’t want to read it.

SJM: So, I imagine that must have been very difficult [for her]. But that was also a long time... [laugh] for an author.

ALM: Really a long time. The book should have been out last year actually, but I mean, she took a look at the way that I portrayed different characters in her life. And in most cases we agreed. There were a few things that we didn’t see eye-to-eye on, but she was always very respectful.

SJM: Of course. So did you ever encounter any difficulty in getting [into Cuba] and acquiring documents? Or was it like no issues whatsoever?

ALM: No, no, no. The same as usual. I mean, the same problems that you usually have when you go to Cuba [laugh], but nothing particularly new.

SJM: But you got there just in time so the timing was good.

ALM: Yeah, and I was always very lucky to have two very good research assistants in Cuba, one [Liliana González Moreno] who was even in Cuba when Tania went to do her concert [with the National Symphony Orchestra]—I was not able to go. I wanted to, but I couldn’t since I was in Cambridge at the time. And then I also had an assistant when I went [to Cuba], who actually organized my whole agenda, and my calendar, and my schedule. And she [Gabriela Rojas Sierra] basically scheduled the interviews with everyone, the places to visit, and the photos. So, I was very lucky in that sense, [especially given that I was] there only for a week.

SJM: So it must have been just seamless once you got there! That’s a dream research trip. And, so, what do you do when you’re writing about someone like Tania, who constantly has a new piece, a new festival she’s conducting, another award she’s won? How do you know when you’re done writing? I can’t imagine, because her work is always amplifying!

ALM: Yeah! I think there are two answers to that question. One is the answer regarding [what] I was going to include in the book.

SJM: Is that where there is the dialogue with Tania in the chapter?

ALM: Yeah, so, it was my idea. Tania initially wanted a more traditional musicological take in which you go over the main works and then describe them to create a narrative based on her representative works. But that [ended up being] too long. I wanted to search for how her [compositional] voice came into being, and look at that trajectory. For me, it was through specific pieces where I could actually trace the commonalities. And to me, by the early 2010s, it’s clear that she has a well-established voice that you can recognize. So that was what I was interested in, and so that was a source of a little bit of tension... [laugh] Also the way that I wrote it included her voice and the voices of other people in a sort of constant dialogue. I think in the end she liked it. But some of the peer-review readers of the book didn’t like it at all—they felt that it was too experimental and led the readers in different directions. But yeah, it was even more experimental in the earlier version! After I revised, it became what it is now.

SJM: I thought of it as a new form of feminist music analysis—a great use of the composer’s own voice in the analysis of her works. So often we try to interpret subjectively what is going on in the composer’s music, but if they’re there and they can assist in the analysis, why not have their voice? And then how did you decide what moment in time to stop writing about her?

ALM: The moment in time was going to be the concert in Cuba, but then Stride happened, and I thought, ‘There’s no way that I cannot include this.’ And this is what I was telling you—this is the moment where the reparation for the events of the early 1990s happens, and it was that mini-metaphor of her life. So that’s why I included [it in] the epilogue.

SJM: Yeah. That makes sense. And so, because I’m imagining you had stopped [writing] and then the Pulitzer Prize happened, the publisher allowed you to add on the epilogue?

ALM: Actually, the prize happened when the page proof had already been approved! It happened around the moment when I got the proofs, so I didn’t really have a lot of space to do anything at all. But I found a moment at the end of the epilogue where I could include a footnote, [laugh[ so I’m like, ‘Okay, why can’t we put a footnote here that speaks about the Pulitzer Prize?’ And the publisher was able to do it, but yeah, it almost didn’t get in there.

SJM: Wow. So, at least you got it into a footnote [laugh]! But what about the title though? Because it seems like you had to change the title, too.

ALM: No, no. The title was already Stride because of the composition. So, Tania had told me that she had gotten this commission; so [the name] was already in the air. She told me about these references to her grandmother, her mother, and to Susan B. Anthony, and this idea of just walking forward [no matter what]. You know where you’re going and you keep going. And to me, that’s life. That’s her life. That’s her.

SJM: Absolutely her. I mean, the most striking photo to me in the whole book—which has so many incredible photographs—but the one that strikes me the most is her playing the piano when she’s eight and she’s looking so intensely at the camera. I suppose anyone who knows Tania knows that look [laugh[. It’s like she’s fully formed as a human at that moment, and that’s the Stride look that says, ‘I’m going to walk this path to its end.’ So as you’re writing, these are really tumultuous years between 2016, ’17, and now, and the conversations on race and gender are changing so rapidly in this country. And I’m wondering how that might have altered any thoughts you had about editing or writing the book during this really weird time in the US?

ALM: Well, it was clear that the issue of race had to be central in the book, but it also had to be negotiated, because, you know how Tania feels; she doesn’t want race to be the thing that defines her, right? I also didn’t want the book to be too theoretical. So I decided to speak a little bit about her in terms of race and gender at the beginning of the introduction, and then just let the book sort out the ideas and the rhetoric the way they stand and let the reader decide. And then, the last chapter is about canonization. To me, it was necessarily the moment to go back to the subject and say, this is how people look at her, regardless of how she feels about it. She’s been seen as an African-American, Afro-Cuban woman, and this is how she’s entered the canon; so let’s try to deconstruct the canon and see how introducing her on these terms into this particular canon is actually doing violence to her as an artist and a person. So that was already in my mind. But also, the more radical moment of [the] race conversation that we had in the United States really happened after the book was already written—during that year in which she had the book, but was not reading it yet. So, it all happened at around the same time.

I think it had more of an influence on how the peer-review readers read the book and how they read those ideas about identity politics, and how they became defensive about Tania’s stance. So, after I got the external reviewer’s comments, basically I needed to make the whole argument more nuanced since the readers had perceived it as maybe a little bit too drastic and too radical, which was definitely not the way Tania was saying it. But, in that moment, I think the revision helped me to smooth out the argument and think about it in a different light.

SJM: Yeah, that’s interesting. So the moment when the readers had the manuscript, then, was really more of the transactional moment with the cultural politics that were happening at the time. I wouldn’t have thought of it that way. That’s fascinating. So, in retrospect, what do you think was the most difficult thing about writing this book?

ALM: Well, I think the most difficult thing was to find that balance between uncritical celebration and critical interventions without being too theoretical, because the book was not meant to be just for academics—it’s for a general audience. So finding that balance was very difficult.

SJM: Do you think that stands as a rule when you’re writing a biography about someone living, someone who’s presumably going to read what you’re writing?

ALM: In general, yes. I think that’s true for most cases. We actually just had a session about that at the [2021] AMS [meeting] with people who were writing about Mario Lavista, John Adams, Bang on a Can, and some others. And that was sort of the common thread, that we need to negotiate because there’s always a question of ethics, no? I think that doing this work about living composers sort of puts that onus on the table in a very obvious way. That is, when we write about dead composers, we don’t see it, but it’s still [there]. I mean, we’re writing about someone, there should be some sort of ethical concern about what we say about these people, right? Regardless of whether they’re living or dead.

SJM: Yeah. We don’t look through that same ethical lens when we’re writing about a composer who’s been dead for a hundred years. But we definitely should—an amazing point.... And what do you think was the highlight of this project for you?

ALM: I think the highlight is related to what I was going to tell you that I was sort of forgetting: this question of celebrating or not celebrating this legacy. And that was one of the things that happened to me throughout years of conversations with Tania and hundreds of hours of recording interviews, especially interviewing people who had been her advisees or who had been her students, or who had been sort of touched by her [teaching and influence]. I already admired Tania as an artist; but [after conducting the research], I gained this understanding of her as a human being who has touched the lives of many people in such a positive way. So how do I speak about that without sounding like I’m just, ‘Whoa, this woman is, you know, [amazing].’ [laughs]. So, that was definitely a highlight of the whole experience, learning this side of a creative person you admire, and [getting to] admire her even more.

Notes

- 1 Although I have edited the interview for length and legibility in this article, the full, unedited interview conducted on 13 November 2021 can be heard, with transcript, at https://www.temi.com/editor/t/SrApt9NkPfTH_iAAd8c7HphJ00yqqMPyqkAQSFT08TtYaoEiTdatfd9VbWU156sTn7xmk4LjgEzJPBqrD_U5Rr4iFJE?loadFrom=Dashboard&openShareModal=False.

- 2 Alejandro L. Madrid and Robin D. Moore, Danzón: Circum-Caribbean Dialogues in Music and Dance (Oxford University Press, 2013).

- 3 Brandon Fradd is a philanthropist who has focused his efforts on music and arts, and since 2007 has been a Trustee of the CINTAS foundation which funds research about and works by Cuban and Cuban-American artists. He commissioned this biography of León through his work with The Newburgh Institute for Arts and Ideas (Madrid, Tania León’s Stride, xiii).