American Music Review

Vol. LI, Issue 1, Fall 2021

By Isaac Jean-François

Upon opening the door, I never knew what to expect. I might encounter images of Tania León at the helm of the Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra; or clad in a leather jacket and boots in front of the old New York Times building alongside fellow composer-performers Julius Eastman (1940–1990) and Talib Rasul Hakim (1940–1988); or maybe offering dozens of Ferrero Rocher chocolates to awe-struck guests at her home.1 I remember coming across all of these facets of León in a visit to her home with Ellie Hisama, now Dean of the Faculty of Music at University of Toronto, and Jennifer Lee, Curator for Performing Arts at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Columbia University. It was incredibly special to be in the presence of so much storied ephemera: original manuscripts and photographs with material history. León spent time looking outside where large trees create a forest view from her back windows; I was getting a glimpse into the natural world that framed so much of her compositional expertise.

My encounters with León’s luminous spirit, both playful and knowing, demonstrate the fullness of her inimitable sonic vision. Her composition gathers disparate musical traditions, like salsa and classical genres, and listens to the movement of creatures on the earth—to alma of humans and nature colliding. Initially, my writing on Eastman led me to an early image of the Brooklyn Philharmonic Community Concert Series organizers, and yet it is León, at the photo’s center, who draws the viewer’s gaze into her captivating mind. In any tempo, León bears a confident look as the conductor and composer of a huge collection of path-breaking works. She crafts with precision, weaving a fabric of sound that encompasses a vast and varied instrumentation.

The opportunity to reflect on León’s archival acquisition, in progress by Columbia University’s library, has been a challenging one. The trouble with writing any definitive history or description of León’s archive, and conceptualizing her oeuvre more broadly, is that it runs up against her emphatic rejection of boundaries and borders. The composer herself maintained many of these precious documents and original materials on her own, with an archival care from which we, as listeners and researchers alike, are privileged to benefit. Any attempt to encapsulate León within a single identity or under the rubric of a particular ideology would collapse the sonic freedom that sounds in her work. León resists easy definition. She is a driven composer who lives her mantra—that self-made cantus firmus—filled with endless compositional vigor.

When I process the many comprehensive accounts of León’s life, I am reminded of Fred Moten’s idea, “consent not to be a single being.”2 As a rule, León warns against any quick apprehension of her form through the analytics of race, gender, and nationhood. Alejandro Madrid’s 2022 biography of the composer “examine[s] the different ways in which Tania León appears in Western art music history narratives.”3 He continues: “León has rejected terms such as ‘black composer,’ ‘woman composer,’ or even ‘Afro-Cuban music,’ in favor of more fluid and strategic ways to highlight the impermanence and transitivity of the human experience.”4 Ironically, this rejection somehow intensifies the archivist’s drive to label León’s compositional verve—to place her energy into boxes that, in her perspective, limit that motion. I personally find this tension to be exciting and generative; encountering images of her at the helm of orchestral and classical music spaces––environments that have strategically absented people who did not fit the categorical image of a “conductor” or “composer” in Western classical idioms—feels incredibly empowering to me.

Walter Aaron Clark, in his 1997 review of León’s Indígena (1991), observes that the piece “commences with an atonal exchange between percussion and woodwinds characterized by a ‘motoric, interlocking, polyrhythmic groove.’ This gives way to a more tonal environment in which León evokes the Carnival season and its music, the comparsa.”5 Song and dance shift gears from sounds of celebration to an ongoing and vibrant scene of affective citation in León’s imaginary. Even a piece like Rituál (1987) for solo piano, dedicated to Dance Theatre of Harlem co-founders Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook, has an emphatic ostinato. This piece jumps over two octaves and hits some of the lowest notes on the piano. Rituál draws listeners to memories of dances and parties, across cultural experience, that might register in the latent corners of our consciousness. Engaging the dexterity of a composer who has created across the forms of opera, dance and orchestra, León invites us to place ourselves within the reach of her sound’s motion.

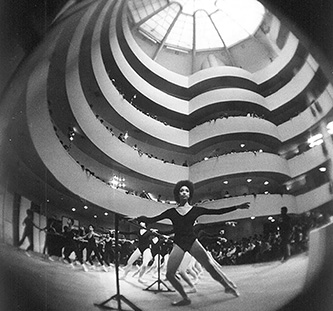

Dance Theatre of Harlem at the Guggenheim Museum, 1971. Photo by Suzanne Vlamis

León’s work invites us to listen in several registers: love, care and constructed sonic fantasies. Her almost fifty years of caring practice has altered my experience of listening, an act already charged by archival encounters. Beyond the confines of institutional holdings,6 León has guided my listening process, allowing me to hear percussion and wind instruments to the fullest. Her ability to play with the lyrical edge of a flute, for example, can flip right into a meditation on the metallic interior of a wind instrument or the taut strings of a piano. Alma (2007), for flute and piano, explores the wide range of possibilities among instruments while allowing them to exist as separate entities. The swaying rhythms of the piece bring the listener into a miniature dance within a brief span of musical time.

León worked with the Dance Theatre of Harlem in New York for over a decade. The company’s premiere in January of 1971 was part of her origin story as a composer and visionary in the genre of sonic choreography and dance. Although I was expecting to find dance photography in her archive, I was almost brought to tears when I saw this photo for the first time. The white spiral interior of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum warps at the seams in this image captured by Suzanne Vlamis. Black motion, steadied by bars, disrupts the dizzying spiral: movement cannot be trapped by the ordering impulse of the museum’s interior. The Guggenheim held the dance company’s debut performance: art historical archives and choreographic motion are part of León’s legacy.7

How do I attend to the chromatic dissonance I experience in both the photographic portraits of León and the works that she has composed—the light and dark, the energy in excess of language, an art deeply rooted in faith and family? León has shared the inspiration she received from her mother in composing her opera Scourge of Hyacinths (1994).8 León draws us into the audible link between mother and child, shifting how we imagine narratives of sonic inspiration. The repetition of a mother’s voice motivates her to create sound that reconfigures loss and remembrance.

With the pandemic still raging and climate change spiraling out of control, León’s brilliance continues to reach, encounter, resolve. Her music, which often implicitly calls for a dance, moves us to continue in this world ethically and joyfully. She embodies the varied ways in which composition in diaspora, outside of strict labels, imagines music’s unheard futures. León encourages us to reckon with sound and to experience dance and flight.

Notes

- 1 William Robin, “A Composer Puts Her Life in Music, beyond Labels.” New York Times, February 7, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/07/arts/music/tania-leon-new-york-philharmonic.html. More context around this image of Tania León alongside Julius Eastman and Talib Rasul Hakim is available online in this striking review of León’s oeuvre.

- 2 Fred Moten, Black and Blur: consent not to be a single being (Duke University Press, 2017).

- 3 Alejandro Madrid, Tania León’s Stride: A Polyrhythmic Life (University of Illinois Press, 2022), 168.

- 4 Ibid., 167.

- 5 Walter Aaron Clark, “Tania Leon. Indígena.” American Music 15, no. 3 (1997): 421-422.

- 6 For more on the specific nature of León’s compositional expanse, see James Spinazzola, “An introduction to the music of Tania León and a conductor’s analysis of Indígena,” LSU Doctoral Dissertations, 2006, 3326. Image of Tania León with baton is available at University of Missouri Kansas City Libraries’ “Tania León Digital Exhibits @ UMKC Libraries,” Shining a Light: 21st Century Music from Underrepresented Composers, Digital Exhibits @ UMKC Libraries. https://exhibits.library.umkc.edu/s/shining-a-light/item/582. (accessed January 21, 2022).

- 7 Mari S. Gold, “Works & Process Rotunda Project Dance Theater of Harlem at 50. Rotunda, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum,” New York Arts: An International Journal for the Arts, https://newyorkarts.net/2019/10/works-process-rotunda-project-at-the-guggenheim-dance-theater-of-harlem-at-50/. (accessed March 30, 2022).

- 8 careergirls, “Composer/Conductor: Scourge of Hyacinths Opera - Tania Leon Career Girls Role Model.” YouTube, January 12, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XpQw_KtSiDA.