American Music Review

Vol. L, Issue 1, Fall 2020

By Malcolm Merriweather

The tradition of unifying voices and instruments has been a vehicle for composers to amplify everything from the mass ordinary to heroic tales from the Bible. Intense and limitless, the grandeur of the symphonic choral repertoire has the power to awaken the imaginations of the audience and its performers. As a conductor and singer, I have a great admiration for the genre, from Bach’s B minor Mass to Mendelssohn’s Elijah. Of course, the requiems of Brahms, Fauré, and Britten resonate with me—they’re heaven on earth for a baritone. Universally recognized, these composers will always be masters of the repertoire, as memorialized in dozens of commercial recordings, films, and documentaries.

When we perform such masterworks and imagine the composers of symphonic choral music, we are surrounded by the images of dead white men. Indeed, as I stood in the splendor of the Eastman Theatre stage for countless performances during my master’s degree, I was literally flanked by busts of Bach and Beethoven. Likewise, texts, articles, and scholarship dedicated to choral literature and twentieth-century music celebrate the musical innovations and masterpieces of white men. Is that the only vision of a master? Twenty years into the twenty-first century, whilst entering an age of cultural revolution and racial reckoning and reconciliation, it is problematic when the visage of an entire entity is heterogeneous. It is just odd. We noticed immediately that something was missing. This void illustrates that this genre, like most facets of classical music, remains largely uninformed and unshaped by Blackness. Concealed from the narrative are the works of about a dozen Black female composers. So imagine my curiosity when in 2018 I stumbled upon a large-scale work by Margaret Bonds.

In the program notes of a concert I attended that summer, harpist Dr. Ashley Jackson made mention of The Ballad of the Brown King, the 1954 cantata composed by Bonds in collaboration with the Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes. While I was familiar with Bonds (1913–72) through her solo vocal works and spiritual arrangements, I had never encountered this cantata or any other extended work. In fact, in all of my education, I had never learned about a Black woman composing a choral orchestral piece. It turned out that the absence of the work from choral literature texts was not even the biggest obstacle to further study. The Ballad had been out of print for decades, and I could not find a single professional-level recording. Eventually, I found a PDF of the piano vocal score and sat down to play through the piece. I was immediately captivated by the setting and made plans to perform and record it.

Bonds and Hughes represent my “dream team” for the making of an oratorio. From the beginning, I was inspired by the outstanding craftsmanship of Hughes’ libretto. The text chronicles the journey of Balthazar, the Ethiopian King, as he travels to Bethlehem to bring gifts to the infant savior, Jesus of Nazareth. Never before had I experienced such rich poetry about a Black man being a king. Eventually, I secured the rights to produce an edition of the now out-of-print cantata. My edition was tailored for a mid-size choir, with a cost-efficient mindset for the orchestra.

Reducing the full orchestration, I fashioned the winds and brass into an organ part and retained the string material; Saint-Saëns’s exquisite Oratorio de Noël, Op. 12, inspired the instrumentation. The harp part was enlivened to add texture that one might miss in the absence of winds and brass. I reconciled and corrected errors in the full orchestra manuscript parts and printed piano vocal score, and edited the vocal parts with breath marks, articulations, and other expressive features. All of these edits were informed and influenced by various aspects of Bonds’ compositional idiom, including her use of expression in her solo vocal works. Characterized by call-and-response textures, jazz harmonies, gospel vocalizations, calypso rhythms, and syncopated gestures, Bonds affirms Black identity and its place in classical music. Helen Walker-Hill describes this perfectly in her text, From Spirituals to Symphonies, African American Women Composers and Their Music: “Her deliberate use of Black musical idioms in these works made a statement about the value of African Americans and their culture.”1

Bonds was also strategic with the stories she selected for her compositions. Her Easter cantata, Simon Bore the Cross, chronicles the deeds of Simon of Cyrene, the Black man who carried the cross of Jesus to the site of the crucifixion. In The Ballad, Bonds and Hughes establish Balthazar as the central character in the Christmas narrative, as a means of providing “the dark youth of America [with] a cantata which [made] them proud to sing.” At its 1954 premiere, The Ballad of the Brown King was a sort of musical antidote for Black people as they marched through one of the most troubling periods in American history. In a letter just before the 1960 orchestral premiere, Bonds expressed to Hughes, “It is a great mission to tell Negroes how great they are.”2

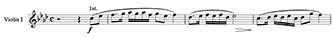

This sentiment is fully realized midway through the nine-movement cantata. Entitled “Could He Have Been an Ethiope?,” the sixth movement contains the most expansive and expressive content of the piece. A thirteen-measure prelude before the tenor solo alludes to something I call the regal motif (Example 1). In the first movement, the regal motif announces the entrance of King Balthazar in an eight-measure introduction. The tempo of the sixth movement is much slower, and we find the contrabasses accompanying the regal motif with an arduous ostinato that pervades most of the movement (Example 2). The instrumental introduction illustrates the long trek of the dark-skinned wise man while metaphorically portraying the journey of Black people during the Civil Rights movement.

In a sense, the movement takes the listener on a royal tour of the great kingdoms of Africa. The choir and soloist ask at various times about the kingships of Ethiopia, Egypt, and Arabia. Regardless of the ethnicity of Balthazar, the choir proclaims, “I don’t know just who he was, but he was a wise man” (Example 3).

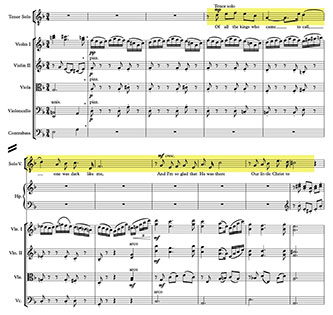

The gesture, with its thirty-second–note fanfare, propels the expedition of the King into what some would label a “heart attack moment”—that is, a moment in a piece that completely takes the listener by surprise. Bonds accomplishes this by dropping the dynamic from forte to pianissimo and reducing the texture to strings and tenor soloist (Example 4). The change in disposition, à la Schubert’s “Gretchen am Spinnrade,” ultimately prepares us for what I believe to be the most important utterance of the piece:

Of all the kings who came to call

One was dark like me

And I’m so glad that he was there

Our little Christ to see

For the repetition of this text, Bonds builds the intensity by adding the full orchestra, choir, and soprano soloist. The choir, in an impassioned plea, repeats “dark like me” and “our little Christ to see,” in preparation for the climax of the entire cantata, as shown in Example 5.

One cannot help but connect the journey of Balthazar to the plight of runaway slaves following the North Star to Philadelphia. These great biblical stories of oppression-turned-triumph were often the basis of spirituals and freedom songs. Singing, central to the slave community, ultimately served as a strategy, since many songs were encoded with messages aimed at leading the slaves to freedom. Bonds’ sixth movement boldly represents the collective struggle of people throughout the world who have suffered in the grips of bondage and disenfranchisement. Her postlude for the movement returns to that opening motif, this time in a D major key, almost as if to say, with relief, “We made it.”

The emergence of the concert spiritual in the early twentieth century represents an important contribution to American vernacular vocal music. Yet, however popular spirituals have become on recitals and choral programs, the genre still remains on the fringe of academia. Considering the lack of attention it receives in music history texts, performers, conductors, and scholars still have much work to do in bringing these works to light. Here Bonds makes another nod to Black culture while also emphasizing the role of Christianity in it. She clearly recognized her responsibility when she said:

I realized very young that I was the link between Negro composers of the past. You see, my mother was friends with all of them. I hear the young Negro composers of today and many of them are trying to reconcile atonality with the Negro idiom and they just don’t go together. I think, if anything, if I deserve credit at all, it’s that I have stuck to my own ethnic material and worked to develop it.3

On 22 September 1960, Bonds wrote to Langston Hughes and said that she yearned to capture a recording of “one good performance” of the cantata.4 That dream was not realized in her lifetime, but in December 2019, The Dessoff Choirs released the first commercial recording of Margaret Bonds’ The Ballad of the Brown King for choir, orchestra, and soloists (AVIE Records). The undertaking was a direct response to my observation of the erasure of Black women from the narrative of the choral orchestral canon.

In the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, recognition of historic and ongoing bias toward Black people in classical music has been widespread. Bonds noted obstacles she faced because she was Black, and she was always aware of gender discrimination throughout her career. As this cultural and social evolution continues to unfold, institutions are making efforts to reveal that American concert music is not just Barber, Copland, and Bernstein, but also Margaret Bonds, Julia Perry, and Valerie Capers. The journey will be long, but now is the time to dismantle the errors of the past and reshape our curricula and repertoire accordingly. With this notion, let us wipe away the residue of oppression and continue to unveil these masterpieces and their masters.

Notes

- 1 Helen Walker-Hill, From Spirituals to Symphonies: African-American Women Composers and Their Music (University of Illinois Press, 2007), 157.

- 2 Margaret Bonds to Langston Hughes, 20 December 1964. Langston Hughes Papers, James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- 3 Walker-Hill, From Spirituals to Symphonies, 159.

- 4 Margaret Bonds to Langston Hughes, 22 September 1960. Langston Hughes Papers, James Weldon Johnson Collection.