American Music Review

Vol. L, Issue 1, Fall 2020

By Stephanie Jensen-Moulton

The Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music is based at one of the most diverse colleges in the nation. To teach at Brooklyn College means daily encounters with diversity in terms of class, race, gender, sexuality, nation, religion, ability, and more. The Brooklyn College Conservatory of Music does not differ greatly from other American music conservatories, but Brooklyn College’s history, geographic location, and general student population does. Most of our students currently come from Brooklyn and generally reflect the borough’s diverse demographic. Today, Brooklyn College is a “majority minority” institution, serving children of immigrants, “dreamers,” and many first generation college students. However, this was not always the case. When Brooklyn College was founded in 1930, it was a predominantly white liberal arts institution. But when CUNY briefly established open admissions in 1970, the result was not only an extraordinary expansion in admissions numbers, but also a much less white, more racially diverse campus.

In the Conservatory of Music, a professor might teach one or more courses in General Education with an enrollment of mostly non-music majors. But the other courses that a professor teaches derive from a curriculum designed for declared music majors. Those music majors have passed an adjudicated audition or have submitted a portfolio of mostly notated musical compositions requiring students to have studied classical music for long enough to prepare a polished audition, or know enough notation and theory to write down their own music.

Since well before the 1970s, the majority of higher education music programs in the US have aligned with European standards, relying on Western music theory, history, ear-training, and keyboard, combined with classical private lessons and ensembles, as the core of a future musician’s training. The National Association of Schools of Music has tailored their accreditation of higher education music programs to this classical paradigm.

Given that K–12 arts programs, music programs in particular, have been on New York City’s budget chopping block since the mid-1970s, only students with economic privilege or the sheer luck to end up in a school zone with a music program will be prepared to take college-level classical auditions. What about students who want to major in music but have not had access to the training needed to audition? These students have pursued other musical opportunities accessible to them and equally as appealing and intellectually stimulating, such as performing musical theater, making beats, playing in bands, or singing with gospel choirs (just to name a few examples). The remainder of this article ponders the connections between curriculum, access, American music, and austerity.

July 2020 protest co-organized by the PSC and ARC, outside the gates of Brooklyn College, with shoes representing faculty and staff who lost health coverage during COVID. Photo by Whitney George

Over the pandemic summer of 2020, both national and local events led Brooklyn College faculty to consider our institution with regard to our history of austerity as it relates to race relations. Beginning in June, CUNY imposed the worst austerity measures in recent memory. The PSC (CUNY faculty and staff union) held numerous protests against class-size increases, cuts to department funding and reassigned time for research and administrative work, and incessant cuts to adjunct faculty and support staff. At these protests, the Anti-Racist Coalition (ARC) emerged as a new and important voice uniting BIPOC faculty, staff, and students. The recognition—indeed, remembrance—that austerity had always been linked to CUNY’s history in admitting Black and Brown students fueled the fire of protest, and calls rang out not only for transparency from our administration, but also for a unified effort to diversify faculty and decolonize the curriculum across schools and departments.

After the murder of George Floyd and the ensuing activism, several faculty in the Conservatory of Music united under the leadership of Douglas Geers, electronic music composer and director of our Sonic Arts program. Meeting frequently over Zoom during the summer, we brainstormed about ways to create access routes into our programs for undergraduate students whose musical experience was outside of the Western art music tradition. A significant objective was to support our existing programs while broadening the department’s intellectual footprint to emphasize cultural analysis of music. Another goal, which seemed practically impossible in the current state of austerity, was to incorporate support for interdisciplinary programs such as Puerto Rican and Latino Studies (PRLS), Africana Studies, American Studies, and Women’s and Gender Studies. All of the aforementioned programs lack adequate administrative support and draw faculty from other departments through cross-listing. After a few meetings, we developed an idea for a BA track in American Music that would combine critical thinking, social justice, and practical experience in American music, all without an admission audition.

***

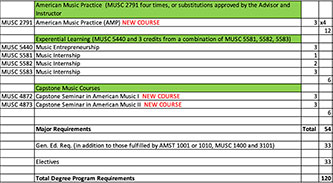

I decided to design a BA track in American Music that incorporated courses already offered by interdisciplinary programs and/or the Conservatory. While serving as chair of the American Studies program, Ray Allen designed a sleek minor in American Music and Culture, with courses cross-listed in Music, American Studies, Africana Studies, Theater, PRLS, and more. All of these courses are offered on a frequent, rotational basis. I also relied on the expertise of performance and technology faculty, selecting important experiential courses from the wide array of electronic music courses written by my colleagues in the Sonic Arts and Media Scoring. Performance colleague Malcolm Merriweather co-wrote one of the only new courses in the degree, American Music Practice (AMP). AMP is a rotating four-semester course of group workshops on different topics, allowing students to experience performing different genres of American music without previous training. This type of course is similar to a continuing education or evening division music class: adult students are learning a new instrument or vocal style in order to broaden their ability to speak multiple musical languages. AMP could even be taught online during our current public health crisis. A typical rotation of topics would include Hip Hop and R&B, Gospel and Praise Music, Musical Theater, and Pan-Caribbean Musics. I could also imagine special topics such as Indigenous Musics, Pop and Rock Experience, and Blue/New Grass. The final elements of the BA track would then be internships and interactive capstone projects.

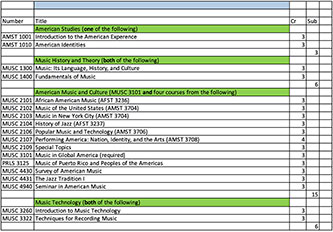

In order to accommodate the needs of the many students at CUNY’s twenty community colleges who transfer to senior colleges, the number of degree-bearing credits was kept at or under fifty-four so that transfer students could step right into this program of study. With that accomplished, the committee submitted the new BA, the new AMP course, and the new capstone course as a package to the Conservatory of Music faculty for consideration, which has now been approved. Below, I’ve included tables outlining what we finally named the BA track in American Music & Culture.

Knowing that higher education music departments all over the US are having conversations of a similar tenor, I’m offering this case study not as a one-size-fits-all solution to a complex and often troubling problem, but rather as one way to begin taking action towards a more just curriculum open to all students. What’s unusual about American music as a place of unity in music pedagogy is that the US is not only a location of global musicking, but also a place where the European art music tradition continues its long history. For faculty who have always taught in the National Association of Schools of Music (NASM) curriculum, or similar, it’s a good time to think about updating and reconsidering what we teach college music students. A colleague of mine recently pointed out that NASM’s curriculum is still rooted in their original 1924 document.1 A track such as the BA in American Music & Culture may prove to be an invigorating creative force for longterm change. Open for admission in Fall 2021, this BA has the potential to bring musicians who were in different practice rooms together as stand mates, co-authors, and activists. For more information, feel free to email BAAmericanMusicCulture@gmail.com.

If you have ideas or a piece to contribute to AMR on rethinking American music pedagogy, please write to us at hisam@brooklyn.cuny.edu.

Notes

- 1 According to their website, NASM is “is an organization of schools, conservatories, colleges, and universities” that “establishes national standards for undergraduate and graduate degrees and other credentials for music and music-related disciplines.” The only mention of American music in their current curriculum appears in Appendix 2.