American Music Review

Vol. XLVIII, Issue 2, Spring 2019

By Sean Colonna, Columbia University

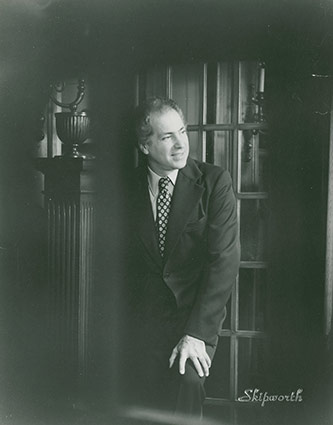

When I first met Maurice Peress during the summer of 2017, we talked for over an hour in the living room of his spacious Manhattan apartment at 310 West 72nd Street. I did not know what to expect from our meeting or where it might lead, and I recall being shocked and humbled that this accomplished conductor and scholar would take such a keen and immediate interest in learning about me and my research. After we settled down in his living room, he began to ask me a series of questions: What did I think my dissertation was going to be about? Did I know about this book, this piece, this recording? Was my last name Italian? Where were my parents from?

This was to be my first of several windows into Maurice’s character. He had a deep-seated love for American music and for the people in his life, particularly those who shared his musical passions.

I returned several times to his apartment that summer with Jennifer Lee, the Performing Arts Curator for Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscripts Library (RBML). Maurice had been battling a terminal illness for some time, and Jenny and I were helping organize his materials for transport to Columbia’s RBML. Ellie Hisama, one of my mentors and professors at Columbia, had recently suggested to Maurice that he house his archive here. The two of them had known one another for decades: Ellie had performed in the student orchestra while Maurice was serving as conductor and instructor at the Aaron Copland School of Music in Queens College, CUNY, and she had also worked as his assistant for three concert reconstructions Maurice mounted as part of Carnegie Hall’s 1989 Jazz Legacy Series. After Maurice visited Columbia and saw the rich variety of material already housed at the RBML, he was convinced he wanted to leave his materials there.

I had the honor of getting to know Maurice both personally and professionally as Jenny and I helped organize the archive. Combing through his over-stuffed boxes and creaking bookshelves, the two of us were regaled with stories—and sometimes, when the mood struck, songs—prompted by a particular book, letter, or picture. This article offers a brief biographic sketch of Maurice’s life as well as a description of a small sample of some of the items in his archive.

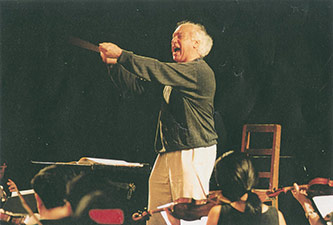

The following list of some of Maurice’s professional accomplishments gives a good sense of the breadth of his intellectual and musical interests: he led the student orchestra at Queens College for over thirty years, conducted several major orchestras (including the New York Philharmonic), premiered Leonard Bernstein’s Mass at the Kennedy Center, orchestrated a number of Duke Ellington’s most well-known compositions, and staged recreations of influential historic concerts such as Paul Whiteman’s premiere of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and the Carnegie Hall debuts of both Duke Ellington and James Reese Europe’s Clef Club Orchestra. He also published Dvořák to Duke Ellington: A Conductor Explores America’s Music and Its African American Roots, which is filled with both archival and ethnographic research pertaining to the training, legacy, and influence of several prominent African American composers.1 As is likely already apparent, Maurice’s life and career did not sit comfortably in any generic category—he was conductor, arranger, entrepreneur, historian, ethnographer, and musician all at once.

Maurice framed his life’s startling trajectory in his aptly-titled memoir, Maverick Maestro: “How does a firstborn son of Jewish immigrants from Washington Heights who decides not to take over the family business and plays jazz trumpet instead end up conducting opening night at the Kennedy Center—or a symphony orchestra in Vienna, or an Ellington premiere in Chicago?”2 He was born in Manhattan on 18 March 1930, and his father, Heskel-Ezra Moshi Peress (later Americanized to “Henry Peress”), emigrated from Baghdad to New York City in 1926, opening a lingerie shop one year later. There he met Maurice’s mother, Elka (Elsie) Frimit Tiger, who had emigrated from Poland with her sister in 1923. Music was a profound influence on Maurice from a very young age. His father would play the oud on Sunday mornings, filling their apartment with the sounds of Arabic music. At age thirteen, Maurice became “infatuated” with the bugle and his love of the instrument would carry him through private lessons, his high school years at Brooklyn Tech, summer performance programs at Juilliard, and his undergraduate studies in music at NYU.3 Although his musical life started with a love of jazz, hearing a rehearsal of “The Infernal Dance of King Kashchei” from Stravinsky’s Firebird during his time at Juilliard was an electrifying “epiphany” for Maurice, “filling [him] with sounds [he] had never thought possible.”4 His love of music continued to grow, and, after a brief stint as a drafted member of the newly desegregated 173rd Negro Regimental Band at Fort Dix, he met his soon-to-be wife, Gloria Vando. They married in the summer of 1955, taking up residence in a small apartment at the corner of Sullivan and West 4th Street (Maurice called the place “very La Bohème”) and after he completed his master’s in musicology at NYU three years later he began working as a trumpeter with the as-yet undiscovered composer David Amram during the early days of the New York Shakespeare Festival in Central Park.5

Maurice’s conducting career surged forward when Leonard Bernstein appointed him Assistant Conductor to the New York Philharmonic for the 1961–1962 concert season, along with John Canarina and Seiji Ozawa. That year brought Maurice not only close personal friendship with Bernstein, but opportunities to learn from both veteran musicians and guest conductors, including the Viennese conductor Josef Krips and the composer-conductor Nadia Boulanger. His connections eventually led him to sign with Columbia Records, which in turn gave him the opportunity to take over the newly vacated position of music director for the Corpus Christi Symphony in Texas. He held that position for the next twelve years, until he took over leadership of the Kansas City Philharmonic in 1974. During his time as a professional conductor, Maurice devoted himself not only to standard repertoire, but also newer, experimental pieces by contemporaneous composers such as Morton Feldman (he premiered Rothko Chapel in 1972) and John Corigliano (conducting his Piano Concerto in 1970).

However, what Maurice called “the musical high point of [his] life” came when Bernstein asked Maurice to conduct the 1971 premiere of Mass for the inaugural concert of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.6 Composed in memory of Kennedy after his assassination, Mass was received with great emotion by the high-profile politicians who had been invited to the final dress rehearsal: “At the end of this first-ever Mass the members of the company, and many in the audience, were shattered, in tears. The sadness and sense of loss—for the Celebrant, for our lost innocence, for John Kennedy—was palpable. That night Ted Kennedy came down the aisle to the pit to thank us. He was deeply moved.”7

In addition to immersing himself in both performing and advocating for classical music, Maurice also maintained his life-long love for and involvement with jazz, working with the Modern Jazz Quartet throughout his time at Corpus Christi and Kansas City. The ensemble was led by pianist John Lewis and “modeled their format after classical chamber groups …Their programs were not simply ’sets’ of tunes strung together, but rather John’s highly developed, formally structured essays on bebop classics and American standards and, of course, the blues.”8 Maurice’s omnivorous musical tastes—spanning the canonical, the avant-garde, and jazz—would remain central to his musical practice for much of his life, and it was likely this ability to treat music as something “beyond category” that led to one of Maurice’s most inspiring and lasting friendships, namely that with Duke Ellington.

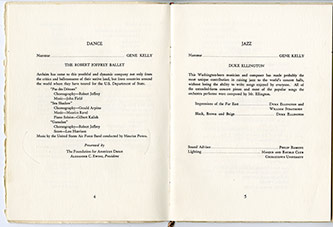

Maurice met Ellington at the White House Festival for the Arts, hosted by the Johnson administration on 14 June 1965. The event itself was designed to showcase the work of some of America’s leading artistic and cultural figures—for one extraordinary day, the White House displayed sculptures by Alexander Calder, paintings by Mark Rothko, and photographs by Alfred Stieglitz. There were performances of pieces by Ned Rorem, George Gershwin, and Bernstein, as well as scenes from plays such as Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman and Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie. Maurice had been invited to conduct the Air Force band for the Robert Joffrey Ballet’s performance during the evening show (hosted by Gene Kelly), and Ellington was there to bring the night to a conclusion. Among the pieces Ellington’s band performed was Black, Brown, and Beige, subtitled “A Tone Parallel to the History of the Negro in America.”9 Although the piece had been premiered during Ellington’s Carnegie Hall debut in 1943, Maurice heard it for the first time that night at the White House. He later recalled that he “realize[d] that Ellington chose to place his ‘tone parallel’ alongside the other American masterworks performed and displayed at the festival, reaffirming his faith in the work, no matter its less-than-enthusiastic reception by most critics and fans when it was first presented.”10

Maurice was inspired by the piece and wanted to conduct a symphonic arrangement of it. When he proposed the idea of orchestrating it to Ellington that night, the composer was skeptical, replying “What’s wrong with it the way it is?”11 Eventually, however, after Ellington heard Maurice’s improved orchestration of a disappointing symphonic arrangement of The Golden Broom and the Green Apple, he asked Maurice to go ahead with his idea to orchestrate Black, Brown, and Beige. The new version was premiered with the Chicago Symphony in 1970. The success of Maurice’s orchestration led him to further collaborations with Ellington, most significantly on Queenie Pie. Commissioned by the National Educational Television Opera Company in 1970, Queenie was to be Ellington’s “opera comique” for television.12 Although it was not completed before the composer passed away, Maurice finished the orchestration some years later and, with the help of Ellington’s son Mercer, mounted a production of the piece in 1986 with the Music Theater of Philadelphia.

At the conclusion of his sixth season with Kansas City, Maurice describes himself as having “[blown] a deep hole in [his] life,” one that it would take him “nine years to dig [himself] out of.”13 After a combination of labor disputes between orchestra players and management as well as an extramarital affair, he left Kansas City having burned many professional and personal bridges. He began to see a psychiatrist, and he describes the results as follows:

Slowly, I learned to forgive myself and earned my way back into the lives of my three beloved children [Lorca, Anika, and Paul], who were making their way in music and the theater … Gloria remarried and built an enviable literary career: editor, poet, publisher, and feminist. In time she, too, would let me into her life again. I met and married a marvelous woman, Ellen Waldron, landscape designer and artist.14

Over the years spent working on rebuilding his personal and professional relationships, Maurice found his way back to New York City as a conductor. Not long after his move, the musicologist and bebop musician Howard Brofsky helped him to find a position as conductor and instructor at Queens College in 1984.

Although he was initially hesitant to take up a teaching position after several decades of working in professional performance circles (“was I cashing in my chips?”), Maurice came to love his work conducting the student orchestra.15 It not only provided him with stability, but allowed him the space to expand his intellectual and scholarly pursuits. During his time at Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center, he not only published Dvořák to Duke Ellington but also organized and conducted reproductions of several historic performances in American musical history.

One such reproduction was mounted on 12 February 1984 at Town Hall, just before Maurice had officially started his second career. For this concert, Maurice reconstructed Gershwin’s debut performance of Rhapsody in Blue, originally conducted by Paul Whiteman in 1924. The research he did in preparation for the concert involved exploring the Whiteman archives in order to determine the other pieces on the program as well as conducting interviews with the few players from that original performance who were still alive at the time. The pianist and lawyer Milton Rettenberg—who knew both George and Ira Gershwin personally and had performed the solo piano part with Whiteman’s ensemble—supplied Maurice with Gershwin’s autograph copy of the piano reduction in addition to his memories of the musicians who performed with him. The concert reproduction was a sell-out and a great success. This inspired Maurice to follow up with several other concert reproductions, offered through Carnegie Hall’s 1989 Jazz Legacy Series—Ellington’s 1943 debut at Carnegie Hall, during which he premiered Black, Brown, and Beige; George Antheil’s 1927 premiere of Ballet Mécanique; and James Reese Europe’s 1912 Clef Club Concert at Carnegie Hall, the first performance in the space by an all-black ensemble.

Maurice’s preparatory work for these concerts led him to many archival sources, most of which pointed to the influence of Antonín Dvořák on many early-twentieth century African American composers. Indeed, he uncovered what he called “an irrefutable historical connection between Dvořák and three seminal twentieth-century American composers. Two of Dvořák’s American composition students, Will Marion Cook and Rubin Goldmark, had in turn become the teachers of Duke Ellington, Aaron Copland, and George Gershwin!”16

Until just a few months before he succumbed to a long battle with leukemia, Maurice maintained both his conducting and teaching schedules. When travel to and from Queens came to be too arduous, he continued giving conducting lessons from his apartment. As I got to know him over the course of his final summer, I was repeatedly struck by how passionate and energetic he was about his work, even as he was wheelchair-bound and occasionally needed to pause for breath. I realized, watching him lovingly go through his papers, scores, notes, and correspondence, what a great gift Columbia would be receiving.

The archive includes a wide range of materials including photographs, scores, correspondence, programs, and research materials. Scholars can access this archive through Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscripts Library, which will soon be featuring a finding aid for this collection.

Perhaps one of the most interesting components of the archive is the collection of the scores for Maurice’s concert reconstructions. Particularly for the three Carnegie Hall reconstructions—Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue premiere, Antheil’s Ballet Mécanique, and Europe’s Clef Club debut—such a trove of musical information will prove invaluable for those interested in the history of these events. Testifying to the meticulousness with which Maurice organized and tracked his materials, the majority of the scores for these pieces also include a complete set of parts, including the pianola rolls for Antheil’s Ballet. Those interested in the history of performance practice and conducting will likely find Maurice’s annotations and preferred bowings informative as well.

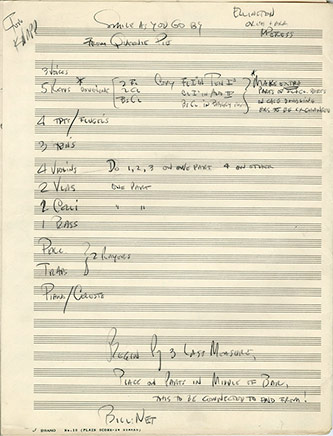

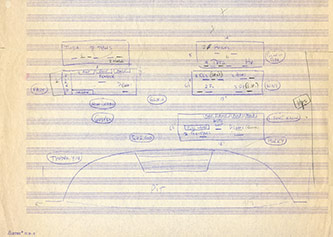

In addition to the scores for his concert reconstructions, there are also scores and parts for those pieces he orchestrated himself. Figures 1 and 2 show excerpts from Maurice’s orchestrations of Black Brown and Beige and Queenie Pie, respectively. A comparison of the re-orchestrated version of the former with its original provides a view into both the techniques of symphonic jazz and Maurice’s painstaking attention to sonic detail. His arrangement of Queenie Pie merits close scrutiny not only for the reasons above, but also because it provides some cohesion to this late, unfinished piece by Ellington.

The archive also includes his annotated score for Bernstein’s Mass, in addition to the preparatory materials Maurice created for rehearsals. Figure 3 shows a page from Maurice’s sketches of the staging, showing his understanding of how the action onstage related to key sections of the piece.

For all their richness and variety, the scores and parts are only one fraction of the material in this archive. In addition to these and much of his correspondence, there are program books from the many concerts Maurice conducted. Perhaps the most fascinating of these is the 1965 White House Festival for the Arts (Figure 4). Leafing through the program booklet provides a sense of the enormous breadth of material presented at this historic occasion, a window into what the Johnson administration held to be exemplary American art and culture.

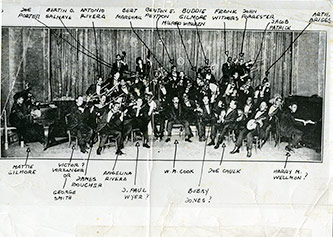

Maurice’s scholarly side is also well-represented in his archive. His research materials for his various concerts and projects have been preserved, offering a wide range of information for historians of American music. An indication of the rigor and care with which Maurice conducted his research for the Clef Club reconstruction, Figure 5 shows his annotations of a photograph of the historic ensemble, complete with the names of each of the players he was able to identify. Similarly detailed information can be found for his other concert reconstructions in addition to the wide range of materials Maurice collected for Dvořák to Duke Ellington.

As this brief overview shows, Maurice’s archive has much to teach us. He left it to Columbia in the hopes that it will contribute to the growing body of research on American musical history as well as provide insights for performers, orchestrators, arrangers and conductors. Although Maurice passed away in December of 2017, his collection reveals his personal affability, intellectual curiosity, and the breadth and depth of his passion for music.

Notes

- 1 Maurice Peress, Dvořák to Duke Ellington: A Conductor Explores America’s Music and Its African American Roots (Oxford University Press, 2004).

- 2 Maurice Peress, Maverick Maestro (Paradigm Publishers, 2015), xii.

- 3 Ibid., 13.

- 4 Ibid., 25.

- 5 Ibid., 45.

- 6 Ibid., 2.

- 7 Ibid., 123.

- 8 Ibid., 140–41..

- 9 “Program for the First Carnegie Hall Concert: 23 January, 1943,” in The Duke Ellington Reader, ed. Mark Tucker (Oxford University Press, 1993), 161.

- 10 Peress, Maverick, 156.

- 11 Ibid., 157.

- 12 Ibid., 128.

- 13 Ibid., 192.

- 14 Ibid., 193.

- 15 Ibid., 198.

- 16 Ibid., 202.