American Music Review

Vol. XLVIII, Issue 2, Spring 2019

By Ray Allen, Brooklyn College, CUNY

Let’s start with an unimpeachable fact—Mahalia Jackson was the most popular and influential black gospel singer of the twentieth century. Her majestic contralto echoed from the floors of countless black churches to the stage of the Newport Jazz Festival to the rarified air of Carnegie Hall. Her songs reached millions of Americans, black and white, through early television appearances and her own nationally syndicated CBS radio show. Her bounty of audio recordings, first for the independent Apollo label and later for the entertainment giant Columbia, won her broad acclaim from church-going gospel fans to aficionados of jazz and American roots music. She wore the well-deserved appellation “Queen of Gospel Music” with grace and dignity.

Jackson’s impact on American music has inspired a substantial body of writing. An autobiography, two biographies, hundreds of newspaper and magazine reviews, and ample portions of standard gospel histories, including Anthony Heilbut’s The Gospel Sound and Horace Boyer’s How Sweet the Sound, have told her life story and recounted her enduring contributions to the American music mélange. Could another book-length study possibly be warranted? Indeed yes, because much of the scholarship on Jackson has tended to be impressionistic. Penned predominantly by adoring journalists and one filmmaker/biographer, the existing literature lacks solid historical sourcing and fails to offer the critical perspective necessary to position Jackson’s life and music in the broader cultural context of black postwar America.

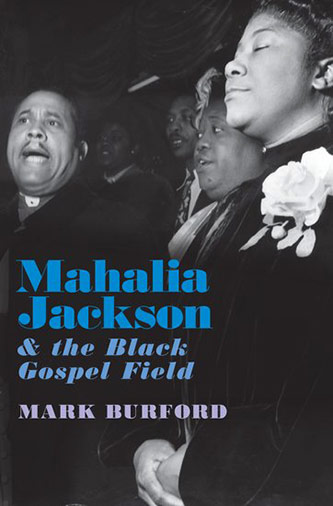

With an eye toward filling this scholarly void, Mark Burford offers Mahalia Jackson and the Black Gospel Field (Oxford, 2019). Burford, trained in musicology at Columbia University, came up in a black Seventh Day Adventist church that did not practice gospel music. Thus he came to the music a bit later in life, first as an avid fan and then as a devoted scholar. As his title suggests, the book purports to be more than a third biography of Jackson. Drawing on the work of French cultural theorist Pierre Bourdieu, Burford situates Jackson and her music within a broader “field” of cultural production that considers “the relations among a diversity of individual agents, particular [musical] works, specific performance practices, sources of prestige, and political and economic dynamics…” (25–26). In other words, he seeks to hyper-contextualize Jackson and her music, first as a means of expanding the history of black gospel practice, and second as a lens through which to view the larger role black musical production played in postwar urban life. Given the magnitude of this task, Burford has focused his investigation on Jackson’s accomplishments during the period stretching from the mid-1940s through the mid-1950s, a pivotal time in her transformation from local church singer to national icon.

Following a provocative critique of previous black gospel scholarship, Burford provides two fairly conventional chapters on Jackson’s early years in her native New Orleans followed by her move to Chicago in the early 1930s. There she teamed up with famed gospel composer Thomas Dorsey and began her long association with the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses. In the fourth chapter he ventures into the world of gospel programs and song battles, identifying them as sites for both religious worship and popular entertainment. Here he introduces the gospel promoter and entrepreneur Johnny Meyers, whose gospel shows propelled Jackson, Ernestine Washington, Georgia Peach, the Dixie Hummingbirds, and dozens of other gospel acts to prominence among New York’s black church-going folk.

Next Burford dives deep into the music, focusing initially on Jackson’s 1946–1954 Apollo recordings. He recounts the history of the New York-based independent label which, under the management of Bess Berman, became a leading promoter of African American jazz, R&B, and gospel during the early post-war years when the major labels showed relatively little interest in black vernacular music. Rather than employing standard Western notation and analysis, Burford encourages readers to engage in deep listening with select examples drawn from Jackson’s Apollo catalogue. Based on stylistic parameters of meter, tempo, and rhythmic pulse, he categorizes her gospel songs as falling into three “feels”: a swing feel (fast tempo, four-beats-to-a-bar articulation, swinging eighth notes), a gospel feel (slower tempo, compound meter), and a free feel (extremely slow tempo, lacking a discernible steady beat, reserved primarily for hymns). In addition, Burford examines Jackson’s renditions of non-gospel songs such as “The Lord’s Prayer,” “I Believe,” and other popular religious songs that Berman encouraged her to record in hopes of reaching a broader, multiracial audience.

Jackson’s Apollo recordings reflect her unwavering commitment to grassroots gospel songs and hymns, but also reveal her willingness to test the waters with more popular religious material and to expand her vocal influences. The performances also caught the attention of white jazz aficionados and helped increase her visibility to such a point that in 1954 CBS radio offered her a nationally syndicated show and Columbia records lured her away from Apollo. Burford devotes full chapters to these developments. The Mahalia Jackson Show was a weekly, nationally syndicated CBS radio program that premiered in September of 1954 and ran through early January of the following year. In this short-lived but influential program, Jackson had to negotiate a new setting and medium—the radio studio, with predominantly white spectators and scripted text between her songs. With an ear toward a national audience she learned to balance her demonstrative gospel arrangements with more staid spirituals and inspirational songs. “You’ve got to remember we’re not in church—we’re on CBS,” she once chided an overly exuberant studio audience (297). Under the watchful eye and ear of Columbia Records’ legendary music arranger Mitch Miller, Jackson further broadened her repertoire and style, beginning with her 1955 LP Mahalia Jackson: The World’s Greatest Gospel Singer. Burford meticulously analyzes Jackson’s 1954 and 1955 Columbia Recording sessions that resulted in arrangements grounded in the black gospel and spiritual traditions but increasingly reflecting the influences of jazz, country, and popular folk styles. As Columbia producer George Avakian ruminated in his liner notes to Jackson’s 1955 Christmas album, Sweet Little Jesus Boy, she could choose to swing with a light jazz beat, articulate with the eloquence of a concert singer, break free with the spontaneity of the gospel spirit, or croon like a romantic balladeer.

Although CBS cancelled The Mahalia Jackson Show in early 1955, the company continued to promote its gospel star by featuring her in a local TV program that was broadcast twice a week to a Chicago audience. Burford devotes the penultimate chapter of his book to Mahalia Sings, which aired thrity-four episodes between March and September of that year. The program was a local rather than a national broadcast, making its success dependent on support from Chicago’s black churchgoers as well as an expanding base of local white listeners. The show firmly established Jackson’s reputation as a local star, a role cemented by her relentless schedule of appearances in neighborhood churches and high visibility mixed-audience events including the Chicago Tribune’s annual Chicagoland Music Festival. Burford ends his story with the city’s 1955 birthday salute to Jackson, hosted by Studs Terkel, and featuring testimonies by a cadre of influential church leaders, journalists, and civic leaders including Chicago Mayor Richard Daley. The granddaughter of Louisiana slaves had risen up to become one of Chicago’s most prominent citizens and an international celebrity.

Burford’s study is built on a solid foundation of historical sources, ranging from an array of interviews and contemporaneous reviews to Jackson’s expansive catalogue of commercial recordings and radio/television broadcasts. The private journal of the singer’s confidant and unofficial assistant, Bill Russell, offers fresh insight into her daily life and personal views on music and religion during the critical mid-1950s period. Burford’s penchant for detail and digression occasionally slow down the work’s flow, but this is a small price to pay for such a richly chronicled narrative. Readers can easily skip over sections that stray too far off the book’s main path.

Burford concludes that Jackson served as something of a “cultural interpreter” as she “shuttled between the church and the world of popular culture, to negotiate and mediate the visceral pleasures new audiences took from the sound of gospel music…” (386). In doing so he illuminates a transformative moment in the development of the gospel field and one that reveals the paradoxical nature of the genre. From its inception, gospel song was rooted in the traditional spirituals, sanctified songs, and folk hymns employed by southern, rural Afro-Christians to worship and commune with their deity. The gospel music that emerged in the north remained anchored in black urban churches, but would eventually find followers among black and white secular listners. LP audio recordings, radio, and the emerging medium of television came together mid-century to usher black gospel music beyond the confines of the African-Ameican church and into the realm of American popular culture. Jackson was a conduit and the most influential player in that crossover drama. With one foot firmly set in tradition and the other stepping confidently forward into the modern world, she set the stage for the contemporary gospel movement that took off in the late 1960s with the Edwin Hawkins Singers international hit “Oh Happy Day.” That scene has continued to flourish into the new millennium with gospel/R&B stars such as Kirk Franklin and Mary Mary. For Jackson, and a few who came before and many who would follow, gospel song was an expression of spiritual entertainment whose sacred and secular parameters demand constant renegotiation.

Is Burford’s Mahalia Jackson and the Black Gospel Field the definitive work on this magnificent singer? Doubtful. While his focus on the early postwar years through the mid-1950s documents her rise from an obscure church singer to an international luminary, he chooses to leave the period from her 1955 birthday celebration up to her passing in 1972 for others to tackle. During this time Jackson continued to record and perform for mixed audiences around the globe while becoming deeply involved with the burgeoning United States civil rights movement. Her rendition of “How I Got Over” at the 1963 March on Washington, where Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, has become legendary. There is much more to say about Jackson and her influence on American music in general, and the gospel field in particular. Burford has set a high bar for future scholarly inquiry.