American Music Review

Vol. XLVII, Issue 1, Fall 2017

By Sarah Weaver, Stony Brook University

Pauline Oliveros at the San Francisco Tape Music Center, c. 1964

Pauline Oliveros (1932–2016) is a luminary in American music. She was a pioneer in a number of fields, including composition, improvisation, tape and electronic music, and accordion performance. Oliveros was also the founder of Deep Listening, a practice that is “based upon principles of improvisation, electronic music, ritual, teaching and meditation,” and that is “designed to inspire both trained and untrained musicians to practice the art of listening and responding to environmental conditions in solo and ensemble situations.”1 While Deep Listening permeated Oliveros’s output since the establishment of The Deep Listening Band in 1988, the first Deep Listening Retreat in 1991, and the Deep Listening programs that continue through present time, the literature surrounding Oliveros’s work tends to portray an historical gap between Deep Listening and her earlier works, such as her acclaimed tape composition Bye Bye Butterfly, a two-channel, eight-minute tape composition made at the San Francisco Tape Music Center in 1965. A main reason for this gap is an over-emphasis on Oliveros’s status as a female composer, rather than a direct engagement with the musical elements of her work. This has caused Bye Bye Butterfly to be interpreted prominently as a feminist work, even though, according to Oliveros herself, the work was not intended this way in the first place.2 Furthermore, historical significance tends to be placed on this piece, and on its relationship with Oliveros as a female composer, instead of portraying her work and significance based on her music alone. Connecting Deep Listening and Bye Bye Butterfly illuminates a continuum of her musical processes, depicting her music more completely. This query explores cultural factors contributing to this historical gap in accounts of Oliveros’s music, locating the roots of Deep Listening in Bye Bye Butterfly and offering a refined pathway for portrayal of Oliveros’s music.

* * *

“Pauline Oliveros is an internationally known American composer, in the forefront of music since the late 1950s.”

- Heidi Von Gunden, University of Illinois Composition Faculty3

“Pauline Oliveros is a disconcerting figure to a great many people.”

- Ben Johnston, University of Illinois Composition Faculty4

Pauline Oliveros’s innovations in a variety of musics have spurred historical as sociations with disparate figures from LaMonte Young to Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage to Cecil Taylor, Laurie Anderson to Annea Lockwood, and across artistic disciplines from IONE to Linda Montano. Amidst the historical multiplicity and polarizations in portrayals of her work, the consistent underlying feature is that she is a woman. This has prompted an over-emphasis on her gender, an excessive characterization of her work as feminist, and a gap in representation of musical ties between her early and later works.

The overemphasis on Pauline Oliveros’s status as a female composer is evidenced consistently across many texts. In Alex Ross’s The Rest is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century (2007), Oliveros is cited within a section on classical music spreading internationally beyond Europe. Male composers Peter Sculthorpe and R. Murray Schafer are listed in acknowledgement of their musical contributions, while composers Franghiz Ali-Zadeh, Chen Yi, Unsuk Chin, Sofia Gubaidulina, Kaija Saariaho, and Pauline Oliveros are grouped together in recognition that they are female. In Paul Griffith’s book Modern Music and After (1995), Oliveros is brought up in a discussion of musical trends of individuality and inclusion in the 1970s. Again, the musical attributes of male composers such as Benjamin Britten and Gerald Barry are discussed, while the female composers are grouped together. In this case, each female composer is given a male comparison. Judith Weir is paired with Franco Donatoni, Gubaidulina with Schnittke, and Oliveros with Terry Riley. Age of Contradiction: American Thought and Culture in the 1960s (2000) by Howard Brick addresses Oliveros in a paragraph about the San Francisco Tape Music Center in the context of an electronic music scene largely dominated by Milton Babbitt’s serialists. Male composers Ramon Sender, Morton Subotnick, Elliott Carter, Leonard Bernstein, Ned Rorem, Charles Wuorinen, John Cage, and Arnold Schoenberg are all presented according to their musical work. The comments on Oliveros are prefaced by stating she is “one of the few well-known women working in new music.”5 In Kyle Gann’s American Music in the Twentieth Century (1997), the main discussion of Oliveros is in relation to John Cage: “If Cage could be said to have a female counterpart, it would have to be Pauline Oliveros.”6

Even in books that are about women in music, Oliveros is prone to be characterized primarily in terms of gender. While publications such as Women Composers and Music Technology in the United States: Crossing the Line (2006) by Elizabeth Hinkle-Turner, and the Norton/Grove Dictionary of Women Composers (1994) display Oliveros’s work on its own terms after being grouped with women in the book titles, another study, omen and Music: A History (2001) edited by Karin Anna Pendle, goes further to emphasize Oliveros as female. This book displays a typical example of the format, beginning with Oliveros’s musical work and extending the portrayal to bring attention to her gender:

Oliveros has won a respectful following, among composers and audiences, as an experimenter and a forerunner in the now widely accepted field of electronic music. Through her many residences at colleges and universities she has spread to a younger generation of composers her ideas about creating a music based on listening. Her concern with meditation and Eastern philosophies recalls the ideas of John Cage, though her music does not. Most poetically stated, Pauline Oliveros is, in her commitment to feminist principles and her exploration of new language of sounds, a musical Gertrude Stein.7

This format is congruent with the broad pattern of consistently categorizing Oliveros’s music as female within the disparate historical groupings of her work, rather than emphasizing the connection of her musical elements on their own terms.

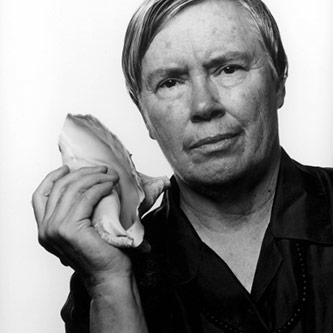

Pauline Oliveros with conch shell, 1995

Historically this factor can also be attributed to the cultural context of Oliveros’s compositional career. Her career has taken place in a field with few women in it, and a cultural era in which feminists have fought for the rights of women. Another component is the masculinist musicological narrative cited by scholars such as Martha Mockus. The discrimination against women in the eras leading up to and including the lifetime of Oliveros led to masculine viewpoints in studying and historically interpreting her music, resulting in an overemphasis on feminism regarding Oliveros. Although Mockus’s interpretations, written from a female viewpoint, continue to cast Bye Bye Butterfly as a feminist piece and furthermore as a lesbian piece, her work nonetheless offers an alternative to the masculine narrative. She views Oliveros’s work “as lesbian musicality—a musical enactment of mid- and late-century lesbian subjectivity, critique, and transformation on several levels.”8 She highlights aspects, such as commitment to pleasure, recognition of the body, importance of group interaction, and the relationship of romantic longing to music-making. Regarding Bye Bye Butterfly, she views this as an “eerie and forceful feminist critique of the opera” and she argues that the work “calls attention to the opera’s distorted representations of gender and race.”9 This scholarly work was a step in broadening interpretation and contextualization of the earlier and later works of Oliveros in musicology through a female perspective. However, Mockus’s interpretation emphasizes the subject matter more than the innovations in electronic music present in the piece, which offer links to Oliveros’s later works.

Oliveros herself has spoken out about women’s issues in music. Famously, in her article “And Don’t Call Them Lady Composers,” published in the New York Times in 1970, she cites issues such as the expectation of domesticity for women, their support of men’s needs and aspirations, and the derogatory usage of “girl” and “lady.” She writes, “No matter what her achievements might be, when the time comes, a woman is expected to knuckle under, pay attention to her feminine duties and obediently follow her husband wherever his endeavor or inclination takes him, no matter how detrimental it may be to her own.” 10 Regarding music, she writes, “Many critics and professors cannot refer to women who are also composers without using cute or condescending language. She is a ‘lady composer.’ Rightly, this expression is anathema to many self-respecting women composers. It effectively separates women’s efforts from the mainstream.”11 Oliveros is explicitly addressing women’s issues up to this point. However, she goes further in the article to show how addressing these concerns is a gateway for healing societal issues:

It does not matter that all composers are great composers; it matters that this activity be encouraged among all the population, that we communicate with each other in nondestructive ways… Certainly the greatest problems of society will not be solved until an egalitarian atmosphere utilizing the total creative energies exists among all men and women.12

This is the broader message of the article, and in a way it is a lens through which to view aspects of Oliveros’s musical legacy. While her work exists in a time and place in which women’s issues need to be addressed, her compositions have transformed this concern into broad human interconnections in her practice of Deep Listening. Healing inner and outer divisions, individually and in music, extending this into society, and committing to authentic expression through listening, are all evidence of an underlying creative process in her work, beyond categorization in terms of sex or gender. To characterize Oliveros as female and her work as feminist is only a partial portrayal that diminishes her significance as a musical and human pioneer. Connecting the musical elements of her early and later works can close this gap and illuminate essences of her music in the field.

An additional cultural factor contributing to the historical gap is the dynamic between metaphysical practice and musical composition during Oliveros’s career. While the cultural dynamics between the metaphysical aspects of Oliveros’s Deep Listening practice and music composition is a broad discussion, specifically among the composers at the San Francisco Tape Music Center, Oliveros is the only composer to have developed a metaphysical sound practice for her music. Experimental composers of her era have openly worked with metaphysical elements in their music, such as John Cage’s use of the I-Ching, Anthony Braxton’s use of ritual in Trillium, and Arvo Pärt’s integration of Russian Orthodox religion in many works. Taking this further into developing a practice based on sound is unique to Oliveros among historically recognized composers in her field. This important link has not been sufficiently addressed in characterizing her work as a whole.

This lack of attention to metaphysics also feeds into the historical overemphasis on her feminism and even into the choice of Bye Bye Butterfly as an historical representation of her work in general. In Oliveros’s book, Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice, and on her artist website, she lists Bye Bye Butterfly, but the piece is not presented as central to describing and defining her work. The musicological placement of Bye Bye Butterfly elsewhere as a work of great historical significance can be traced to both an overemphasis on feminism and a deficiency in scholarship that does not deal sufficiently with the relationship between Deep Listening and Oliveros’s musical compositions.

* * *

In 1969 New York Times music critic John Rockwell named Bye Bye Butterfly one of the most significant pieces of the decade.13 Created at the storied San Francisco Tape Music Center along with other early notable works of Oliveros such as I of IV, Bye Bye Butterfly exemplified her early innovations in music that also pioneered the emergence of electronic music as a field. Made as a two-channel tape piece, the technology utilizes two oscillators, two-line amplifiers in cascade, two tape recorders in a delay set-up, and a turntable with a recording of Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly (1904). Oliveros arranged the equipment, tuned the oscillators, and created the composition in real time. The piece includes a section that processes a recording of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. The resulting sounds, made by distorting and deconstructing the recorded music, are largely interpreted as feminist, representing the end of discriminatory practices against women from the culture in which the piece Madama Butterfly was made. For example, Mockus quotes Heidi Von Gunden’s analysis, which argues that the “tape-delay technique and the frequency modulation produce wavelike gestures resembling sonic good-byes to Butterfly.”14 Mockus goes further to suggest Bye Bye Butterfly is a reclaiming of the butterfly as a beautiful symbol of lesbian sexuality.15 Howard Brick, in his book Age of Contradiction: American Thought and Culture in the 1960s, states that Oliveros is a woman whose “irreverent Bye Bye Butterfly” is “a spontaneous performance on synthesizer, emitting long, weird sounds like cricket choruses, against a backdrop of a scratchy record of a Puccini aria.”16 This association of Oliveros’s “irreverence” with her status as a female composer is compoun ded by his surface level description of the music.

Bye Bye Butterfly has a multilayered relationship with feminism. During my inter view with Oliveros in October 2014, she revealed that the choice of material for the piece was a “synthesis,” that is, the choice of material was intuitive and circumstantial rather than a pre-planned decision. The recording of Madama Butterfly happened to be in the studio where she was making the piece; she did not plan ahead of time to use this recording. Her focus was on the musical decisions with in her tape music techniques and improvisational synchrony. The processing of the Madama Butterfly recording was only a portion of the piece. This is further confirmed by Oliveros in the book The San Francisco Tape Music Center: 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-Garde (2008), where she states that the selection was “fortuitous” and happened by “chance.”17 These distinctions point to the feminist element as a by-product of the piece rather than its central purpose. Furthermore, regarding the first release of the recording of the piece as part of a compilation recording in 1977 titled New Music for Electronic and Recorded Media, which contained works only by women composers, Mockus documents that Oliveros chose to submit Bye Bye Butterfly. Oliveros said the choice was based on its short length (eight minutes). In the liner notes, the picture accompanying the piece is not of Oliveros herself, but rather of a male graduate student who had taken on her daily roles that weekend as part of a performance art festival. All of the other photos in the liner notes are pictures of the female composers themselves, while the image of Oliveros’s male stand-in creates a play on gender and illustrates the piece’s multilayered relationship with feminism.

However, this element is generally over-emphasized in the historical placement of Bye Bye Butterfly and its relationship to her later compositions. As Oliveros states, her focus was on the musical decisions within her tape music techniques and improvisational synchrony. She describes to Mockus how she mapped out the instrument as a kind of performance architecture, rather than deciding the content ahead of time.18 Oliveros’s tape music techniques and improvisational architecture are th e central revolutionary elements of Bye Bye Butterfly that also continued on to be developed in her later works. The interpreted element of feminism in the content was a component but has been given too much historical emphasis in communicating the essence of the piece and of Oliveros as a composer.

* * *

The first Deep Listening Retreat was held in 1991. The practice was formalized in Deep Listening (2004), where Oliveros acknowledges that her collection Sonic Meditations (1971) is the basis of Deep Listening. Oliveros has also practiced Deep Listening in the acclaimed Deep Listening Band since 1988, together with Stuart Dempster, the late David Gamper, and guest musicians. Additionally, she composed Deep Listening Pieces (1990). Other books related to Deep Listening have been written by her collaborators IONE and Heloise Gold, compilations of Deep Listening piec es and writings by students and practitioners have been published, and the practice has permeated Oli veros’s compositions. The Center for Deep Listening (formerly Deep Listening Institute) is located at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York.

The name Deep Listening, according to Oliveros, combines Deep as “complex and boundaries, or edges beyond ordinary or habitual understanding” with Listening as

...learning to expand the perception of sounds to include the whole space/time continuum of sound—encountering the vastness and complexities as much as possible. Simultaneously one ought to be able to target a sound or sequence of sounds as a focus within the space/time continuum and to perceive the detail or trajectory of the sound or sequence of sounds. Such focus should always return to, or be within the whole of the space/time continuum.19

The practice of Deep Listening involves “a variety of training exercises drawn from diverse sources and pieces especially composed by Pauline Oliveros and other Deep Listening practitioners. Exercises include energy work, bodywork, breath exercises, vocalizing, listening and dream work.”20 In creative practice, Oliveros cites this experience:

My performances as an improvising composer are especially informed by my Deep Listening practice. I do practice what I preach. When I arrive on stage, I am listening and expanding to the whole of the space/time continuum of perceptible sound. I have no preconceived ideas. What I perceive as the continuum of sound and energy takes my attention and informs what I play. What I play is recognized consciously by me slightly (milliseconds) after I have played any sound. This altered state of consciousness in performing is exhilarating and inspiring. The music comes through as if I have nothing to do with it but allow it to emerge through my instrument and voice. It is even more exciting to practice, whether I am performing or just living out my daily life.21

The writings on Deep Listening thus far have been largely by Oliveros, her collaborators, practitioners, and students, and the role of Deep Listening in Oliveros’s music has not yet been fully integrated into the historical literature. The practice has spread internationally and Oliveros’s music work in Deep Listening is being received increasingly in artistic institutes. A key in integrating Oliveros’s work as a whole historically is connecting Deep Listening with her early works such as Bye Bye Butterfly.

* * *

Connections between Bye Bye Butterfly and Oliveros’s later work in Deep Listening, can be found in her approach to improvisation, the choice of Madama Butterfly as synthesis rather than intention, tape music as a predecessor to electronic music, and drone aesthetics associated with meditation. Furthermore, Oliveros states her own connection between these entities in her book about Deep Listening:

Through the sixties I became absorbed in electronic music making. With this medium I began to find the sounds that interested me and were most similar to the sounds in my inner listening. Two of my pieces from this period– I of IV and Bye Bye Butterfly were released on recordings and have become classics of the period.22

The use of improvisation is certainly a main connecting element. Contemporaries of Oliveros in experimental music such as John Cage were not drawn to improvisation and questioned its validity. However, Cage commented on Deep Listening in this quote in 1989: “Through Pauline Oliveros and Deep Listening I finally know what harmony is. . . . It’s about the pleasure of making music.”23 The quote is further evidence of the male casting of Oliveros in a feminine tone by referring to “pleasure” rather than to her tangible musical contributions. Beyond pleasure, Oliveros embraced and innovated the Free Improvisation movement in jazz that was emerging at the time of Bye Bye Butterfly and continued her version of this in the development of her Deep Listening work. Her Deep Listening Band performs improvisationally while engaged in Deep Listening and her Deep Listening Pieces utilize text parameters for improvisation. Similarly, Bye Bye Butterfly had a set of tape techniques and recorded material for improvisation in manifesting the piece. Oliveros’s citing of improvisational synthesis in assembling Bye Bye Butterfly relates to her approach in Deep Listening as well and could be considered an early form of Deep Listening. The Deep Listening practice and pieces expanded to involve multiple elements such as focal attention, global attention, body work, multidimensional listening, and dream work. Oliveros’s use of improvisation is more broadly articulated in her work with her colleagues in the Improvisation, Community and Social Practice group. Fischlin and Heble describe the process of improvisation as “the other side of nowhere,”

...a metaphor for the alternative sound-world of improvised music making, and perhaps more notably, for the new kinds of social relationships articulated in a music that, while seeming to come out of nowhere, has profoundly gifted us with the capacity to edge beyond the limits of certainty, predictability, and orthodoxy.24

This is a way to frame cultural aspects of improvisation in Oli veros’s early and later works without overemphasizing feminism.

The link between the tape music format of Bye Bye Butterfly and Oliveros’s later electronic music is clear. This was a trend in music composition in addition to Oliveros’ s individual progression. More distinctly, her Expanded Instrument System (EIS) developed out of her way of performing Bye Bye Butterfly. The EIS is an interactive technology system for performance inv olving improvisation, sophisticated delay systems with replicas and modifications of sounds, and spatializ ed speakers for playing into the past, present, and future of the sounds. The performer has control of various parameters to transform th eir acoustic sound input, in the same way Oliveros used analog devices to pr ocess the sounds of Bye Bye Butterfly. EIS is a main system Oliveros utilized in performance for Deep List ening concerts.

Aesthetically Oliveros’s usage of drones in Bye Bye Butterfly is a precedent for her Deep Listening music. The iconic recording of the Deep Listening Band in 1988 in the reverberant Fort Worden Cistern established the ongoing drone aesthetic of the group. Oliveros’s compositions Four Meditations for Orchestra (1997), The Heart of Tones for ensemble (1999), DroniPhonia for iPhones and multi-instrumentalists (2009), and Tower Ring for gong, chorus, and mixed instruments (2011) show a continuation of drones in her work.

Over time, these musical elements have been retained and expanded in Oliveros’s work. The use of improvisatory elements within a composed architecture combined with Deep Listening has created such a variety of work that what is musically categorical in Oliveros’s work is her process in creating music.

* * *

Historically, Oliveros’s works tend to be put into many groupings rather than a single defining movement. For example, in Twentieth-Century Music: An Introduction (2002), Eric Salzman groups Oliveros in “Non-Western Currents and New Age Music.” In Electronic and Experimental Music: Pioneers in Technology and Composition (2002), Thomas Holmes recognizes Oliveros’s role in the development of “Open and Closed Systems.” Writings on the San Francisco Tape Music Center certainly focus on her breakthroughs in tape music. Others make sweeping characterizations of her music. Elizabeth Hinkle-Turner, in Women Composers and Music Technology in the United States: Crossing the Line (2006), describes Oliveros’s work with the Deep Listening Band as “Combining her contemplative aesthetic with her considerable creative knowledge and abilities in the electroacoustic medium.”25 Fischlin and Hebel summarize her work in this way:

Since the 1960s [Oliveros] has influenced American music profoundly through her work in improvisation, meditation, electronic music, myth, and ritual. Many credit her with being the founder of present-day meditative music as well as being the founder of Deep Listening. All of Oliveros’s work emphasizes musicianship, attention strategies, and improvisational skills.26

Another broad statement by music critic John Rockwell appears in the New York Times: “On some level, music, sound consciousness and religion are all one, and she would seem to be very close to that level.”27 These disparate representations of significance in Oliveros’s work are evidence of non-consensus. The attempts to make holistic characterizations are highly generalized, while over-specification on elements that are not central in her work are rampant.

The focus on Oliveros’s musical process is not as definable in historical texts that a researching for “isms.” Therefore the field looks to define specific innovations in her musical “materials,” or to focus on personal characteristics such as being female, and group her with related composers. This has resulted in many different groupings and has not adequately communicated her significance. Oliveros’s central, encompassing, and radical transformation is her codification of Deep Listening, which permeates all of her work and which has revolutionized music in ways the field is still finding ways to articulate. The more the field can address this and connect her work together, the more the early labels can be transcended and the essence of Oliveros’s historical significance can be expressed.

Notes

- 1 “Deep Listening,” Deep Listening Institute, accessed 7 November 2014, http://deeplistening.org/site/content/about.

- 2 Pauline Oliveros, videoconference interview with author, 21 October 2014.

- 3 Elaine Barkin, “Four Texts,” Perspectives of New Music 23, no. 1 (Autumn–Winter 1984): 102.

- 4 Ibid.

- 5 Howard Brick, Age of Contradiction: American Thought and Culture in the 1960s (Cornell University Press, 2000), 137.

- 6 Kyle Gann, American Music in the Twentieth Century (Schirmer Books, 1997), 161.

- 7 J. Michele Edwards, with contributions by Leslie Lassetter, “North America Since 1920,” in Women and Music: A History, edited by Karin Anna Pendle (Indiana University Press, 2001), 342.

- 8 Martha Mockus, Sounding Out: Pauline Oliveros and Lesbian Musicality (Rutledge, 2008), 2.

- 9 Ibid., 26.

- 10 Pauline Oliveros, “And Don’t Call Them Lady Composers,” New York Times, 13 May 1970.

- 11 Ibid.

- 12 Ibid.

- 13 John Rockwell, “Ten Best Pieces of Electronic Music of the Decade,” Archives of the New York Times (December 1969).

- 14 Mockus, Sounding Out, 24.

- 15 Ibid., 26.

- 16 Brick, Age of Contradiction, 137.

- 17 David W. Bernstein, “The San Francisco Tape Music Center: Emerging Art Forms and the American Counterculture (1961–1966),” in The San Francisco Tape Music Center: 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-Garde, ed. David W. Bernstein (University of California Press, 2008), 30–31.

- 18 Mockus, Sounding Out, 32.

- 19 Pauline Oliveros, Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice (Deep Listening Publications, 2004), xxiii.

- 20 Ibid., 1.

- 21 Ibid., xix.

- 22 Ibid., xvi.

- 23 “Deep Listening,” http://deeplistening.org/site/content/about.

- 24 Daniel Fischlin and Ajay Heble, “The Other Side of Nowhere,” in Fischlin and Heble, eds., The Other Side of Nowhere: Jazz, Improvisation, and Communities in Dialogue (Wesleyan University Press, 2004), 1.

- 25 Elizabeth Hinkle-Turner, Women Composers and Music Technology in the United States: Crossing the Line (Ashgate, 2006), 23.

- 26 Fischlin and Heble, eds., Other Side of Nowhere, 420.

- 27 “Deep Listening,” http://deeplistening.org/site/content/about.