American Music Review

Vol. XLVII, Issue 1, Fall 2017

By Adam Tinkle, Skidmore College

In 1966, Gordon Mumma wrote in a letter to David Tudor that Pauline Oliveros was “representative for the West Coast” of the Sonic Arts Group.1 The Sonic Arts Group, or SAG, was the name used briefly before finally settling on Sonic Arts Union, or SAU, by the touring group of composer-performers Robert Ashley, David Behrman, Alvin Lucier, and Gordon Mumma. Oliveros never toured as an SAU member, but as Mumma’s letter suggests, she was closely connected with the group and with Tudor, who, as a key older mentor, was also considered, early on, to be an SAG member.

Oliveros has been primarily celebrated, especially since her passing, for two rather distinct bodies of work: the music for electronic tape that she produced during her affiliation with the San Francisco Tape Music Center (late 1950s–1967), and the continuum of mindfulness-and participation-oriented work stretching from her Sonic Meditations (begun around 1969) through the Deep Listening practice. By contrast, little has been written about the transitional era in Oliveros’s career, between her time at the Tape Music Center and her first articulations of the text instructions that became the Sonic Meditations. This essay emphasizes the intersections between Oliveros and the SAU during this transitional period, illuminates their shared project in live electro-acoustic music, and asks three main questions: How did it come to pass that she became the “West Coast representative” of the SAG? Despite not becoming, in the end, a touring performer in SAU, in what ways did she participate in this artistic community? How did her musical aesthetics coincide with, differ from, or influence SAU members, and how did theirs influence hers? Towards a provisional answer to this last, thorniest question, it seeks to interpret the core aesthetic project the SAG artists all shared. This casts a fascinating light Oliveros’ best-known work, the first of her Sonic Meditations, and suggests the genesis in electronic music of her movement away from electronics circa 1970.

Oliveros became connected to the SAU through David Tudor. As an early-career composer somewhat geographically cut off from Cage’s New York-centric orbit, Oliveros leveraged the resources and scene she was building in the Bay Area to bring Tudor to San Francisco for a series of performances, informally dubbed Tudorfest, sponsored by the Tape Music Center and Pacifica radio station KPFA.2 In addition to marking the first of several collaborations with Tudor, this concert appears to be Oliveros’ first encounter, albeit indirect, with any of the future SAU members, in the form of the music of Alvin Lucier. Tudor performed a now largely forgotten piece of Lucier’s for scored physical actions that may or may not make sound—very much in the vein of Cage’s Water Walk or any of the other Fluxus scores that Tudor was performing widely throughout the early 1960s. Also somewhat Fluxus-flavored was the piece Oliveros wrote for Tudor to perform with her, Duo for Accordion and Bandoneon with Mynah Bird Obligato: the players perform on a see-saw, accompanied by the singing of an actual bird in a cage.

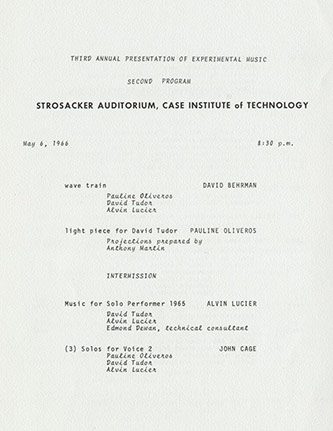

This first Tudor-Oliveros collaboration quickly flowered into more; in 1965, they perform Applebox Double at the ONCE Festival (thus networking with future SAU members Ashley and Mumma, who ran the festival). By mid-1966, Tudor and Oliveros are performing together at Case Institute of Technology in Cleveland, having added Alvin Lucier to their unnamed troupe to perform their own works and those by Cage, as well as David Behrman’s Wave Train.3

In contrast with the fully notated scores and Fluxus aesthetics of the 1964 concerts, this 1966 program reflects movement towards what SAU concerts would soon become when that group began touring in 1967. Not only is the emphasis squarely on electro-acoustics, but critical too is the fact that these works are being collectively performed by a “union” or “collective” of composers. While this 1966 program still features some works where the performers are “interpreters” of the score of an absent composer, SAU appearances would eventually feature works only by the assembled composer-performers. In these years, performer Tudor and composer Cage were slowly breaking away from the older, more traditional model that decouples scorewriting composer from performer and realization. By contrast, the composer-performer model, which was seen as less bound to European music tradition, perhaps more democratic, and certainly more collectivist, was one in which Oliveros was steeped. She had been actively involved in musical collectivism through the Tape Music Center, and had been appearing since at least 1964 as an electronics composer-performer, in the vein that would soon become associated with the SAU.

Scholarship on Tudor depicts his becoming a composer as an outcome of the highly collaborative and co-authorial work that playing Cage’s scores required him to do. But Gordon Mumma has observed that collaborating with Oliveros in 1964–66 was among “the most important motivation[s] for Tudor’s flowering as a composer.”4 Indeed, the circumstantial evidence suggests that Oliveros was also a key influence on moving Tudor towards performing on instruments other than the piano (as in the Duo for Accordion and Bandoneon), on performing in a scoreless, essentially improvisational modality (as in Applebox Double), and on opening his compositional voice beyond sound and music to include light and other multimedia (as in Light Piece for David Tudor). A few months after the Cleveland performance with Oliveros and Lucier, Tudor would make his debut as a composer with Bandoneon (A Combine), which combines these features.

While Oliveros would not ultimately tour with the SAU, her activities between 1967 and 1970 were marked by the dialogue she was having with its members, and with Tudor. Many of these exchanges are oriented around interests that are already emerging in the 1966 collaborations with Tudor and Lucier, including of the exploration of the natural resonances of spaces and objects, and particularly in making these “natural” sonic features sound through feedback. Behrman’s Wave Train is an exploration of piano resonances sounded through microphone feedback, Lucier’s Music for Solo Performer influentially inaugurated bio-feedback music, and several of Oliveros’ tape pieces that she produced during the summer of 1966 riffed on similar ideas by creating feedback and delay loops with two or more tape machines. Mumma was beginning to refer to such systems as “cybersonic,” suggesting how these musical uses of audio and control feedback were inspired by cybernetics, which was becoming widely known for its use of electronic circuits to model ecosystems and organisms.

It was during these years of intense focus on feedback and other “cybersonic” concepts that the extended SAG “family” formed one of her primary communities of collaborators and interlocutors. Upon leaving San Francisco for a faculty position in the newly-formed, experimentation-focused music department at the University of California, San Diego, her archive suggests that her activities became densely interlocked with the SAU’s. Some highlights:

1967: Lucier records Oliveros’ choral composition Sound Patterns, as well as some of the Cage Solos for Voice they had performed together in Cleveland, on the Extended Voices LP, released on the “Music of Our Time Series,” produced by Behrman. Oliveros then invites Lucier to UCSD during her first months working there, where he tries and fails to make tape recordings of the natural resonances of the ionosphere. However, while hanging out with Oliveros, Lucier buys a bunch of conch shells from a seaside shop and conceives of the piece Chambers. They get a bunch of Oliveros’s students to give the piece’s first performance during Lucier’s visit, blowing into the conch shells and thereby sounding the ir natural resonance.

1968: Lucier and Oliveros are reading the same book about bats and echolocation. The book inspires Lucier to write the piece Vespers, while Oliveros quotes the book in a 1968 essay called “Some Sound Observations.”5 Also described at length in the same essay is Bob Ashley’s The Wolfman, a piece she would also assist her UCSD students in realizing early the same year.6

1969: Oliveros writes Bob Ashley to proposes that they co-create a piece called Big Mother meets the Wolfman, a performance which would include The Wolfman, as well as onstage, impromptu personal conversations between the two composers. Her proposed use of conversation as a compositional element bears great resemblance to its use in Ashley’s The Trial of Anne Opie Wehrer, a piece that Oliveros mentions in the same letter, and which she calls “one of the most significant and satisfying works I’ve had the good fortune to experience in some time. It will certainly change my life.”7

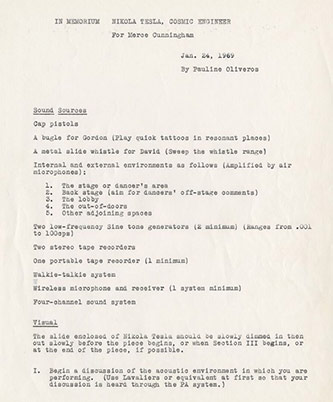

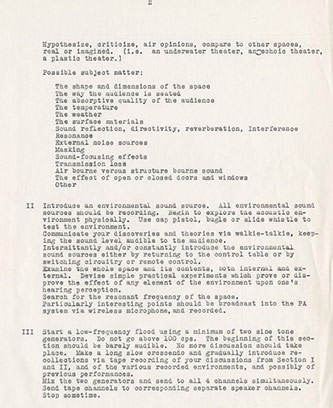

The same month, Merce Cunningham’s dance company, whose touring musicians are David Tudor and SAU’s Gordon Mumma, commissions Oliveros to write the music to accompany the Cunningham dance work CANFIELD. The piece she writes, In Memoriam Nikola Tesla, Cosmic Engineer, has a title resembling four of Bob Ashley’s mid-1960s works, all titled “In Memoriam” for historical figures. Oliveros’ Nikola Tesla also derives much of its sound material, like Ashley’s Trial, from impromptu conversation between the performers: the score’s first section directs performers to “Begin a discussion of the acoustic environment in which you are performing.” Thus, the piece yolks Ashley-esque conversation-as-musicalmaterial to an exploration of natural resonance, the guiding pr eoccupation of the SAG family. In its first section, performers simply talk about the room acoustic, discus sing “sound reflection, directivity, reverberation, interference, resonance,” among other “possible subject matter” for discussion suggested by the score.8 However, in its second section, the performers “begin to explore the acoustic environment physically,” and “use cap pistol, bugle, or slide whistle to test the environment,” thus suggesting similarities to Lucier’s Vespers, another task-based work that orients attention towards the acoustics of a performance space, as performers try to echolocate around it.

1970: Mumma and Tudor serve as lead artists in coordinating the Pepsi Pavillion at the Osaka World’s Fair. They work with Bell Labs engineers to design a domed structure embedded with speakers and microphones, with a remarkable, reflective acoustic. They invite each of the SAU composers, as well as Oliveros and several others, to produce pieces for this purpose-built electro-acoustic musical architecture. Most of the proposed works by Oliveros, Tudor, and the SAU composers, focus on the acoustical resonance of the structure, although Pepsi pulled funding before most of the pieces are realized.

Around this time, the density of Oliveros’ direct connections with the SAU artists precipitously drops off, suggesting an end to the era when she was undoubtedly the “representative for the West Coast” of this group—although she occasionally reunited with various members of the group across the ensuing decades, most notably when Ashley included her, along with the four SAU composers, as one of the seven composers featured in his 1976 film Music with Roots in the Aether.

The centrality of acoustical or “natural” resonance as a key source of musical content for Tudor and Lucier is widely recognized.9 Though Oliveros undoubtedly shared a variety of artistic interests with SAU members, this one musical concern seems central. The Pavilion catalogue from Expo ‘70 gathered evidence of how persistently, almost obsessively, the SAU composers as well as Tudor and Oliveros fixated on this idea. In numerous ways, they approached a single, centering objective: to attune listeners to the acoustical characteristics of the physical spaces we inhabit, and, especially to make audible the resonant modes of acoustical volumes.10 These musical uses of resonance suggest both continuities and breaks in the history of experimentalism: they align with Cage’s calls for indeterminacy and composerly non-intentionality, but they tend to break with Cage’s intense dedication to score-making and score-reading as the essential tools to disrupt musical habit. Instead of consulting the I Ching, these “resonance” composers consult the space in which they are performing to derive authentic and meaningful musical content, attempting to decouple themselves from musical history while linking their performance aesthetic to the here and now, to the ineluctable, pre-symbolic Real that underlies all sonic experience.

Oliveros’s In Memoriam Nikola Tesla, Cosmic Engineer moves towards figuring this insight not merely as knowledge, but as power. The work’s title seems to reference a possibly mythic incident in which Tesla caused an earthquake in New York City by tuning an oscillator to the resonant frequency of the building in which he worked, thereby demonstrating the fearsome physical force that acoustical resonance can conjure. “Search for the resonant frequency of the space,” the score asks, and then “Start a low-frequency ood using a minimum of two sine tone generators” of 100 hz or lower. Such instructions can be understood as Oliveros’s invitation to her performers, Mumma and Tudor—who she well knew were also obsessive explorers of resonance—to meditate on and to more or less reconstruct Tesla’s earthquake, imagining themselves as “cosmic engineers” capable of extending their vibrational agency from music into tactile, material building-shaking. It is tempting to view Mumma and Tudor’s next major project, the Osaka Pavilion—which, with its embedded speakers and microphones, could self-sense, self-actuate, and morph its own resonance—in light of Oliveros’ invitation to “cosmic engineering.”

Is anything really gained by trying to adjudicate which piece or composer inaugurated this “resonance aesthetic”? Certainly there is a good argument to be made that Oliveros’s San Francisco-era Applebox performances, in which a variety of implements are used to make sounds on contact-miked, loudly amplified apple crates, look forward to pieces like Tudor’s Rainforest, Lucier’s Chambers, and many other SAU pieces that involve using minimal means to lay bare the acoustical characteristics and sound the resonant frequencies, of the objects, spaces, and volumes that we find in everyday life. In her writings, however, Oliveros nominates Ashley’s The Wolfman, from 1964, as a key work epitomizing the aesthetics of resonance in live electronic music (and perhaps inaugurating it as well). The Wolfman is a piece in which the performer controls the wailing feedback of a vocal microphone that is amplified through a PA system by placing their mouth directly in front of the microphone and shifting their vocal formant, thereby employing their own vocal cavity as an audio filter on the room’s feedback. Ashley, who had worked in both acoustics and speech research at the University of Michigan, had evidently discovered the surprising equivalence of these two seemingly disparate forms of resonance, the vocal and architectural. The Wolfman rests upon the possibility of superimposing those resonances we can control with our bodies upon those resonances that come to us as given, fixed, and unchanging; both kinds of resonances are just preferential tendencies to oscillate with greater energy at some frequencies than all the others. The piece suggests a cybernetics or an ecology of acoustical resonance, demonstrating both the electronic sound system’s points of control and its irreducible interrelatedness and contingency. Moreover, for the performer, there is room for agency within the system: we are endlessly subjected to resonance, but we are also subjects who resonate.

In describing “a magnificent performance of Bob Ashley’s Wolfman” in the 1968 essay “Some Sound Observations,” Oliveros writes, “My ears changed...All the wax in my ears melted. After the performance, ordinary conversation at two feet away sounded very distant. Later, all ordinary sounds seemed heightened, much louder than usual. Today I can still feel Wolfman in my ears. MY EARS FEEL LIKE CAVES.”11 Thus, a music built from the entanglement of the resonances of bodily and architectural cavities “opens” the ears not in the metaphorical sense of dismantled prejudices, but rather in a more literal sense of establishing the human ears as capacious acoustical chambers in their own right.

The Wolfman appears to have conveyed to Oliveros that, like apple boxes, pianos, conchs, and concert halls, our bodies too are chambers, and this insight soon leads her on a path that bears little resemblance to the subsequent path of Tudor or the SAU composers. Oliveros’s somatic reformulation of “resonance aesthetics” crystallizes in the first of the Sonic Meditation texts that Oliveros wrote in 1969, “Teach Yourself to Fly,” the key soundmaking instruction of which reads “Allow your vocal cords to vibrate in any mode which occurs naturally.” Thus, this piece asks its performers to activate or amplify the natural resonance of a particular acoustical volume or chamber, while its use of language like “mode” and “naturally” signals the piece’s links to the SAG family’s terminology and cosmology. But by locating such chambers within the body, the piece obviates the need for electronics: the breath provides the amplification. Thus, where the great majority of Tudor’s and SAU’s works must be performed by cybersonic tinkerers with technical know-how and access to gear, Oliveros headed in a different direction: a music of “natural” resonances in which anyone can participate.

Oliveros’ decision to filter the cybersonic attention to natural resonance back into acoustic music completes a feedback loop of another sort. If cybernetics sought to model biological life with circuit diagrams that emphasized energy flows and their feedbacks, and if the SAU composers made audible such circuits as electro-acoustic musical systems, Oliveros’s “Teach Yourself to Fly” returned the resonant outcome of this inquiry to the zone of biological life.

Notes

- 1 Gordon Mumma to David Tudor, 9 September 1966, box 57, folder 3, David Tudor Papers, Getty Research Institute. Quoted in Andrew Dewar, Handmade Sounds: The Sonic Arts Union and American Technoculture (Unpublished dissertation, Wesleyan University, 2009), 52.

- 2 “Three Concerts with David Tudor,” program for concert series dated 26 March through 8 April 1966, MSS 102, box 13, Pauline Oliveros Papers, Special Collections & Archives, Mandeville Special Collections, UC San Diego Library.

- 3 “Third Annual Presentation of Experimental Music, Second Program,” 6 May 1966, box 13, Oliveros Papers.

- 4 Mumma, email correspondence with Andrew Raffo Dewar, 23 April 2006. Quoted in Dewar, Handmade Sounds, 87.

- 5 Pauline Oliveros, Software for People: Collected Writings 1963–1980 (Smith Publications, 1984), 25.

- 6 “A Midnight Concert,” 26 January 1968, box 13, Oliveros Papers.

- 7 Pauline Oliveros to Robert Ashley, 11 January 1969, box 1, folder 16, Oliveros Papers.

- 8 Pauline Oliveros, In Memorium Nikola Tesla, Cosmic Engineer, typescript score dated 24 January 1969, box 4, folder 6, Oliveros Papers. Elsewhere, the title of Oliveros’ piece is styled In Memoriam: Nikola Tesla, Cosmic Engineer.

- 9 See, for example, Matthew Rogalsky, “‘Nature’ as an Organizing Principle: Approaches to Chance and the Natural in the Work of John Cage, David Tudor, and Alvin Lucier,” Organised Sound 15, no. 2 (2010): 133–36; You Nakai, “Hear After: Matters of Life and Death in David Tudor’s Electronic Music,” communication +1: 3, article 10; Christoph Cox, “The Alien Voice: Alvin Lucier’s North American Time Capsule 1967,” in Douglas Kahn and Hannah Higgins, eds., Mainframe Experimentalism: Early Computing and the Foundations of the Digital Arts (University of California Press, 2012).

- 10 Billy Klüver, Julie Martin, and Barbara Rose, eds, Pavilion (E.P. Dutton, 1972).

- 11 Oliveros, Software for People, 18–19.