American Music Review

Vol. XLVI, Issue 1, Fall 2016

By Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., University of Pennsylvania

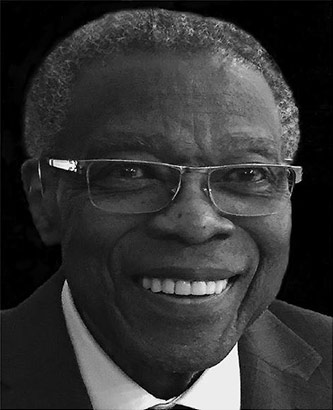

Samuel A. Floyd, Jr. 1937-2016

It would take a book to fully explain the importance of Samuel Floyd to music scholarship. And it’s going take many years to measure his impact. Anyone who experienced his work ethic, drive, focus, encyclopedic knowledge, and professional mastery knew they were in the presence of the best. Sam Floyd possessed an expansive and creative wingspan. It beaconed scholars, activists, composers, performers, archivists, philanthropists, entrepreneurs, university administrators, foundations, publishers, and audiences. His sheer intellectual force was only matched by his generosity of spirit. He used his resources to showcase the scholarship of others and through that bigheartedness created a field of inquiry he called “black music research.” Black music research could only be called a big house, thanks to Sam. At his now-fabled conferences one would experience live new music, living composers, in-process scholarship, in the foxhole mentoring—all with the sweet touch of a family reunion. Elders taught while young folks pondered, questioned, and of course made mistakes. Without sounding too nationalist about it, the intellectual space Sam created felt like a village in all good senses of the word, but in a downtown hotel.

Everyone seemed as surprised as I to learn upon meeting Sam—the scholar who changed the map—that he was such an understated man. Sam’s professionalism was so legendary and awe-inspiring that I pause to discuss anything too personal here. I’m more than comfortable, however, sharing how he affected me directly and how he influenced the trajectory of our discipline.

One of Sam’s most lasting contributions to the broader field of American music was his use of the term “black music research,” a pre-hashtag phrase that expressed some of the political urgency of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. As he began to institutionalize his ideas through scholarship, fundraising, and organizing, many joined his call. Scholars and musicians of all stripes attended biannual conferences of the Center for Black Music Research (CBMR), which Sam founded in 1983. They joined in with the common purpose of approaching black music research with the seriousness and comradery that Sam modeled. A gifted convener, Sam convinced established music societies to meet in conjunction with the CMBR. The crossfertilization of ideas that resulted through the years certainly can be felt in the books published in University of California Press’s Music of the African Diaspora series, which he initiated and edited.

When his work took a theoretical turn in the early 1990s, he applied the insights of poststructuralism, history, and literary theory to black music research through his application of the important scholarship of Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Sterling Stuckey. This move culminated in a groundbreaking article in Black Music Research Journal (a semi-annual publication of the CBMR) on the ring shout ritual and his Call-Response concept, a work now considered fundamental to black music studies.

I met him in the mid-1980s. Because of my lack of scholarly experience, I literally “fell off the turnip truck” and landed in his office at Columbia College after reading about him and his work and discovering that we were both Chicagoans. I was pursuing a Master’s degree in music education and needed a research project. He kindly assigned me something to do that took much too long to complete—a straight-forward survey instrument to determine the demographic makeup of music department faculty in the United States. How he had the patience to deal with someone wholly ignorant of the scholarly world he represented (and who was also a father, choir director, accompanist, bandmate, public school teacher, and private piano teacher) is beyond me. Yet Sam coaxed that project out of me somehow. It became my first publication written under the name “Guy Ramsey,” a hustling musician seeking an advanced teaching certificate for a pay raise and who thought that the brief article would be his last publication. Sam seemed to know better.

From that point on, I listened carefully to Sam’s directions. I attended the graduate program he suggested. And I worked with the sole advisor he strongly recommended, his good friend, the inestimable Richard Crawford, who did the daily dirty work of teaching me this business. Sam’s was one of the steady voices that helped me muster the endurance to make it through graduate school, the land of self-doubt, stipends, and pity. As I learned more about what I didn’t know, we became closer, with him graciously allowing me to engage in conversations about his work. As I moved through the ranks, our intellectual relationship matured. Although we would remain mentor and protégé for most of the time I knew him, it always made me feel like a bigshot after having one of our deep shop talks. Those exchanges took place in person or by phone—rarely on email as I recall—and they were foundational for me not just thinking like a scholar but feeling like one.

I admired Sam’s swag. He moved with ease through the academy and achieved his success, from my viewpoint, with a graceful stealth. Yet beneath his quiet exterior there was an activist’s fire. What confounds me to this day is how Sam convinced many from around the world to join his mission. And he did it all as a “cool gent,” a smooth, seemingly unflappable get-it-done man who was easy to admire but difficult to mimic. Sam gave as much respect as he received. I’m sure there are countless stories about how his example helped younger scholars, gave them voice and a rigorous read without belittling or berating them. He was, indeed, one of the most encouraging people I’d ever met. And if you were fortunate to have had conversations with Sam, you learned almost immediately that it was his musicianship (and not necessarily his unsurpassed organizational abilities) that sat at the core of achievements. He knew so much music—from concert music to the most obscure blues—that he could see connections where others did not, and worked tirelessly to instill his ideas into academy discourse.

I don’t think I ever got over the fact that Sam answered my phone calls through the years. He was a star to me. To share a laugh with him was one of things that made me feel at home in this skin in my chosen profession. The confidence he demonstrated in my abilities through the years gave me reasons to keep on pushing despite doubts and obstacles both real and imagined. His career made my own possible.

When someone has been as formative to one’s life of the mind as Sam was to mine, the past tense of it all is impossible to grasp. I’m currently ending a semester in which I taught The Power of Black Music, his magnum opus that changed how many of us think about African American music making. It was fascinating to see a new generation of students turn onto his ideas, proving their continued relevance. Sam worked hard to stay current, and I think it would have made him happy to see young adults debating his ideas with enthusiasm. As for me, re-reading words that changed my life drove home our collective loss. But it also inspired hope that witnessing the impact of a life well-lived with such dignity and purpose could change the world permanently for the better. We should all strive to do as well.