American Music Review

Vol. XLVI, Issue 1, Fall 2016

By Malcolm J. Merriweather, Brooklyn College, CUNY

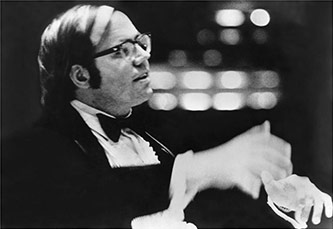

2016 was a particularly poignant year of loss for the music world. In pop music, the world bid farewell to ground-breaking artists like David Bowie, Prince, and George Michael. On 12 July 2016 the world of choral music lost a great luminary with the death of Gregg Smith. During the second half of the twentieth century, Smith set the standard for professional choirs when he established the Gregg Smith Singers and was widely admired for his contributions to the field of contemporary choral composition through interpretation, commissioning, and recording.

Gregg Smith was born on 21 August 1931 in Chicago, Illinois to Myrtle and Howard Smith. He earned a B.A. in music and an M.A. in composition from the University of California at Los Angeles. His primary composition teachers were Lukas Foss and Leonard Stein, and his conducting and ensemble mentors were Raymond Moreman and Fritz Zweig. Throughout his career, Smith served on the faculties at Ithaca College, the State University of New York at Stony Brook, Peabody Conservatory, Columbia University, and Manhattan School of Music.

In 1955, he founded the Gregg Smith Singers in Los Angeles. At the Contemporary Music Festival in Darmstadt, Smith and his singers were featured in Time (September, 1961, 73) after a successful performance of music by Schoenberg, Krenek, and Ives. This was one of the first instances in which the choir received international acclaim for outstanding tone, technical precision, and intonation. Smith led the professional vocal ensemble for more than fifty seasons, earning worldwide praise through festivals, domestic tours, and international residencies. Smith recorded more than 100 albums with the Gregg Smith Singers, winning Grammy Awards for Best Choral Performance in 1966, 1968, and 1970 for Ives: Music for Chorus, The Glory of Gabrieli, and New Music of Ives, respectively.

With his ensemble, Smith led many premieres of contemporary works, as well as revivals of early American music. Their repertoire has included the premieres of Igor Stravinsky’s Requiem Canticles and William Duckworth's Southern Harmony; the complete choral works of Arnold Schoenberg and Elliott Carter; revivals of works by Charles Ives, William Billings, and Victor Herbert; pieces by Edwin London, Blas Galindo, Jorge Córdoba, Irving Fine, Morton Gould, William Schuman, Ned Rorem, and other twentieth century composers; and classics by Giovanni Gabrieli and Heinrich Schütz. In 1973, Smith furthered his commitment to American music by founding the Adirondack Festival of American Music in Saranac Lake, New York. For over thirty-four seasons the festival consisted of a choral workshop for amateur musicians, choral-reading sessions for composers, and concerts that featured notable composers from around the world.

Throughout his career, Smith collaborated with the some of the most influential composers and conductors of the twentieth century. He was held in high regard by Leonard Bernstein, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland, Lukas Foss, Robert Craft, Milton Babbitt, Igor Stravinsky, and many other leading figures of his generation. In 1988, the American Academy and Institute for Letters and Arts presented Smith with the Lillian and Nathan Berliawsky award in recognition for his contributions to “serious American music.”

Smith was an admired and prolific composer with over 400 choral, orchestral, theatre, and chamber works, many of which have been published by G. Schirmer, Music 70, Laurendale, and E.C. Schirmer. His compositional output can be grouped into four categories: original choral compositions; chamber and solo vocal; holiday music and folk song arrangements; and musical theater arrangements. My dissertation “Now I Walk in Beauty, Gregg Smith: A Biographical Essay and Complete Works Catalog” examines the qualities of text treatment, rhythm, form, phrase analysis, harmony, and expressivity that distinguish Smith’s compositions.

At UCLA, Smith credits Lukas Foss with teaching him the emerging compositional innovations of the twentieth century. It was here as a graduate student that he began to explore the music of Charles Ives, and where he encountered an article by the same composer, “Music and Its Future,” that would shape his own compositional method:

[The] distribution of instruments or group of instruments or an arrangement of them at varying distances from the audience is a matter of some interest; as is also the consideration as to the extent it may be advisable and practicable to devise plans in any combination of over two players so that the distance sounds shall travel from the sound body to the listener’s ear may be a favorable element in interpretation. It is difficult to reproduce the sounds and feeling that distance gives to sound wholly by reducing or increasing the number of instruments or by varying their intensities. A brass band playing pianissimo across the street is a different-sounding thing from the same band, playing the piece forte, a block or so away. Experiments, even on a limited scale, as when a conductor separates a chorus from the orchestra or places a choir off the stage or in a remote part of the hall, seem to indicate that there are possibilities in this matter that may benefit the presentation of music, not only from the standpoint of clarifying the harmonic, rhythmic, thematic material, etc., but of bringing the inner content to a deeper realization (assuming, for argument’s sake, that there is an inner content). (Charles Ives, “Music and its Future,” American Composers on American Music, ed. Henry Cowell [Stanford University Press 1933], 191–98)

The article had a profound impact on Smith’s choral compositions. He began to reject the rigid two-dimensional paradigm and confines of the concert hall. His original music is often scored for multiple choirs, instrumental ensembles, and soloists. These musical components are always intended to be positioned spatially within the performance venue. As in the cases of Jazz Mass for Saint Peter’s Church (1966, 1972), Holy (1992), Mass in Space (1982), and Moreman Magnificat (1975), Smith provides a descriptive diagram of performance configurations for the conductor. Beware of the Soldier (1968) utilizes three separate forces—children’s choir and wind quintet; soprano and string quartet; and men’s chorus and brass quintet—all in separate parts of the room. Similarly, his Earth Requiem (1996) echoes Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, with choir and orchestra on stage and children’s choir with portative organ in the distance.

Smith is known for his tuneful melodies, while harmonic structures move back and forth from traditional to non-functional. His most difficult pieces for choir, requiring advanced or professional singers, are often motivic, with emphasis on the linear voice leading in each vocal part that results in an often dissonant harmonic idiom, as in Landscapes (1957), Ave Maria (1966), Concert Madrigals (1960), and Exultate Deo (1957).

Smith occasionally used twelve-tone technique, as in the Sanctus of the Jazz Mass for Saint Peter’s Church (1966, 1972), which is composed on a row based on a series of fifths that he also utilized in the Suite for Harp (1964) and Theme and Variation for Piano (1965). At other times, like Ives, his harmonies are polytonal or olymodal, as in Two Whitman Songs (1995), On the Beach at Night (1995), and Magnificat (1959). In Alleluia: Vom Himmel Hoch (1978), a macaronic piece using German and English, Smith explores ostinato figures within a multi-dimensional context. In pieces like Sound Canticle (1974), elements such as rhythm, text, and duration are at the discretion of the performer. Other non-traditional features in Sound Canticle include tone clusters, glissandi, whispering, speaking, improvised pitches, and graphic notation of both pitch and rhythm. Compositions like Babel (1969) include aleatoric elements like Sprechstimme, ad libitum speaking, and fragmentation of words.

Smith’s long association with the Texas Boys Choir led to many commissions for treble choir. These works often feature pleasing melodic figures and canonic motifs. His understanding of the children’s voices is demonstrated in Bible Songs for Young Voices (1963) and Songs of Innocence (1969). Smith was a master of imitative polyphonic forms: he wrote more than fifty canons, and they also appear frequently within other compositions. The deceptively titled Simple Mass (1976), for two-part treble voices, creates many challenges for the singers, with polychords, tone clusters, and mixed meters. Smith is highly regarded for sensitive text setting, and has drawn on a wide variety of literature, from the poetry of John Milton to e.e. cummings; sacred texts; words by his contemporaries Kim Rich and Gomer Rees; and his own texts.

Chamber music and solo vocal music occupy an important position in Smith’s output, and he often wrote pieces for people close to him. Most of the solo vocal works since 1970 were written for his wife, Rosalind Rees. The clarinet was his favorite instrument, but he also wrote for other instruments, including violin and viola in major chamber pieces such as Fallen Angels (1998), written for Linda Ferriera, and Trio on American Folk Song (1981). A recording of Smith’s chamber works for soprano voice and instruments, titled Delicious Numbers with the soprano Eileen Clark, is expected to be released in early 2017. Gregg’s final recording project, a 2-CD set titled 20th Century American Choral Treasures, was released in October 2016 by Albany Records. The album consists of remastered stereo tape recordings made for the nation’s bicentennial in 1975-76. This retrospective recording with the Gregg Smith Singers demonstrates the depth of his influence in contemporary American music with compositions by William Schuman, Leonard Bernstein, and Randall Thompson. The album includes the first-ever recording of Lukas Foss’s cantata The Prairie, conducted by its composer.

Smith and his ensemble earned many awards over the years. Highlights include Chorus America’s prestigious Margaret Hillis Award (2001) for choral excellence; the Composers Alliance’s Laurel Leaf Award (2003) for distinguished achievement and fostering American music; and Chorus America’s Louis Botto award for Entrepreneurial Spirit (2004) “for a lifetime of devotion to choral music and unflagging creativity in finding ways to bring it to a broader public, through outstanding performances, recordings, and the preservation and dissemination of choral manuscripts.” Smith earned honorary doctorates from the State University of New York at Stony Brook and St. Mary’s College, Notre Dame. In 2014 Dennis Keene and Voices of Ascension (New York City) awarded the Perrin Prize to Smith for a lifetime contribution to the arts.

Gregg Smith will be fondly remembered for his masterful conducting that inspired several generations of singers, and for his advocacy for contemporary composers and their choral music. Barbara Tagg, my mentor and a Smith protégé, concisely summed up his life: “‘Now I Walk in Beauty’ is a Navajo text he set as a simple canon many years ago; Smith has walked in and created beauty throughout his life, inspiring a generation of singers, composers, conductors, and audiences across the United States and well beyond.” I am lucky enough to have been one of the recipients of Gregg’s many gifts. As a first year doctoral student I boarded a Metro North train from Harlem to Yonkers where I was to approach Gregg Smith about being the subject of my dissertation. Gregg and his wife Rosalind (Roz) warmly welcomed me into their home—and our journey began. Over the next three years, I made the familiar trip to the Smith’s home and interviewed Gregg. From the comfort of their cozy living room I sat across from Gregg, perched in his big leather chair. With pencil, note pad, and iPhone voice memo engaged, I listened as he shared musical experiences, events, and jaw-dropping anecdotes—the Stravinsky stories were my favorite. With perfect pitch, an infallible ear, and knowledge that knew no boundaries, Gregg Smith was one of the most caring, humble, gracious, and loving individuals that I have ever met. Now he walks in beauty.