American Music Review

Vol. XLII, No. 1, Fall 2012

By Sean Wilentz, Princeton University

Editors Note: This paper was delivered as the keynote address for the Woody Guthrie Centennial Conference held at Brooklyn College on 22 September 2012.

On February 16, 1940, a freezing blizzardy day, Woody Guthrie—short, intense, and aged twenty-seven—ended a long hitchhiking journey East and debarked in Manhattan, where he would quickly make a name for himself as a performer and recording artist. Nearly twenty-one years later, on or about January 24, 1961, a cold and post-blizzardy day, Bob Dylan—short, intense, and aged nineteen—ended a briefer auto journey East and debarked in Manhattan, where he would quickly make a name for himself as a performer and recording artist—not as quickly as Guthrie had, but quickly. Dylan had turned himself into what he later described as "a Woody Guthrie jukebox," and had come to New York in search of his idol. Guthrie had come to look up his friends the actors Will Geer and Herta Ware, who had introduced him to influential left-wing political and artistic circles out in Los Angeles and would do the same in Manhattan.

Two different stories, obviously, of two very different young men a generation apart—yet, more than he might have realized, Dylan partly replayed his hero's entrance to the city where both men would become legends. Whether he knew it or not, Dylan the acolyte and imitator was also something of a re-enactor.

Almost three years later, having found his own songwriting voice, and having met and learned more about Guthrie, Dylan, in one of the eleven free-verse poems that served as the liner notes to his 1964 album The Times They Are A-Changin', recalled his early days in New York but remarked on how distant they seemed from Guthrie's:

www.dylanstubs.com)">

www.dylanstubs.com)">

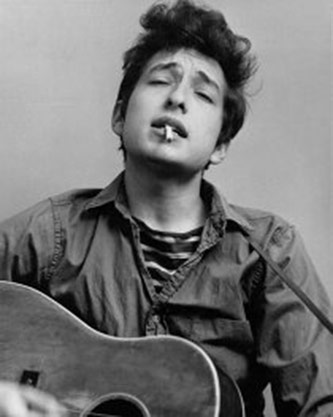

Bob Dylan (1963), Courtesy of the Bob Dylan Picture Archive (www.dylanstubs.com)

www.woodyguthrie.org)">

www.woodyguthrie.org)">

Woody Guthrie, Courtesy of the The Woody Guthrie Foundation (www.woodyguthrie.org)

In times behind, I too

wished I'd lived

in the hungry thirties

an' blew in like Woody

t' New York City

an' sang for dimes

on subway trains

satisfied at a nickel fare. . . .

an' makin' the rounds

t' the union halls

but when I came in

the fares were higher

up t' fifteen cents an' climbin'

an' those bars that Woody's guitar

rattled . . . they've changed

they've been remodeled. . .

ah where are those forces of yesteryear?

why didn't they meet me here

an' greet me here?

"In times behind": at the end of 1963, far from nostalgic, Dylan was already on the road that would eventually lead to making art out of the all-night girls whispering on the D train, in a decidedly sixties, not thirties, New York. The old times were alluring; they seemed simpler, less expensive, full of scuffling CIO union hall solidarity, lived in a moral universe of black and white, of "Which Side Are You On?"—but those times were scattered and buried deep. Besides, Dylan had declared, in an earlier piece of free verse, "I gotta write my own feelins down the same way they did before me."1

Still, for Bob Dylan, then as now, moving on and making it new never meant artistic repudiation, despite what some of his injured admirers have claimed over the years. "The folk songs showed me the way," he insisted; "[w]ithout "Jesse James" there'd be no "Davy Moore," he explained; "An' I got nothing but homage an' holy thinkin' for the old songs and stories." More than thirty years later, he would still be describing "those old songs" to one writer as "my lexicon and my prayer book."2

The time span between Guthrie and Dylan's arrivals, between 1940 and 1961, saw the expansion, decline, and early transfiguration of the politicized culture of the Popular Front, especially in New York. Initiated and orchestrated by the Communist left (which included Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and the rest of the Almanac Singers and the Almanacs' offshoots) to advance its cause, Popular Front culture in its various forms was always connected to Communist and pro-Communist politics. But it also spread outward during World War II to inform and inspire a broader culture of the common man that flourished in the national mainstream until the end of the 1940s. Dylan and his fellow folkies, the sixties newcomers, were impressed and inspired by some of the best of that displaced art of "yesteryear," and they were not the only ones.

A few blocks up MacDougal Street from where Dylan was playing in the Gaslight, maybe on some of the same nights, in a little boîte around the corner on Eighth Street, you could hear Barbra Streisand, not yet twenty, deliver her renditions of her favorite 1930s and 1940s songwriters, including the team of Yip Harburg and Harold Arlen—the latter an on-again, off-again Republican voter, the former decidedly not. In 1962, young Streisand also appeared on a revival album of the 1937 pro-union theatrical Pins and Needles—originally sponsored by David Dubinsky's stalwartly anti-communist International Ladies Garment Workers Union, yet written and performed in the Popular Front music show style, and with musical contributions from, among others, Marc Blitzsten. Fifty years later, just considering the work of Streisand and Dylan, the music that evolved from the polyglot Greenwich Village of the early 1960s not only endures, it flourishes—a remarkable swatch of the nation's cultural history that is also a permutated cultural inheritance from the 1930s and 1940s. Along with his own living songs, being a large part of that bestowal is one of Woody Guthrie's greatest artistic legacies.

In the case of Guthrie and Dylan, the story of the bestowal has become a familiar, even clichéd set piece of a younger man picking up an older man's mantle and persona and then running with it. But the history is richer and more complicated than that. The similarities and continuities of their respective Manhattan arrivals, for example—the thicker social context—are too often neglected. (It is worth remembering that we are considerably more than twice as many years removed from the young Bob Dylan coming to New York than he was from the young Woody Guthrie coming to New York.) The barrooms and union halls and social forces of the hungry thirties may not have met and greeted Dylan in 1961, but some of the people did, and not just Woody Guthrie. So, in fact, did at least one of the barrooms.

It could not have been otherwise for anyone seeking out the stricken Guthrie in New York and finding him at the Sunday gatherings at Bob and Sidsel Gleason's apartment in East Orange. There Dylan met and sang to his hero and mingled with other younger folk music enthusiasts like John Cohen, Ralph Rinzler, and Peter LaFarge, but he also mingled with a shifting assembly that included, among others, Pete Seeger, Harold Leventhal, and, from time to time, Alan Lomax. Back in Manhattan, Sing Out! magazine carried on a sectarian succession of Seeger's People's Songs from the 1940s; Sis Cunningham, a former Almanac, started up Broadside magazine in 1962; Moe Asch and Folkways Records were still very much going; Lee Hays, Earl Robinson, and others were in or around the scene, or at least dropped by from time to time. There were many other genealogical and musical tendrils, including some that crossed generations, like those that connected Robinson's sometime collaborator David Arkin to his son Alan, the future actor, to Alan's fellow hitmaker with the Tarriers, the non-political Erik Darling, to Darling's eventual replacement in the group when Darling joined the Weavers, Eric Weissberg. For many more people than Pete Seeger, the so-called folk revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s was an unbroken continuation of what they, with Woody Guthrie, had undertaken two decades earlier and had been doing all along as best they could.

Young Dylan's New York physical surroundings in the early 1960s also overlapped with the peripatetic Guthrie's from the early 1940s. Guthrie spent his first New York night, ironically, in the relative luxury of the Geers' Fifth Avenue apartment close to the theater where Will Geer was playing Jeeter Lester in the Broadway production of Erskine Caldwell's Tobacco Road. But before he and his wife-to-be Marjorie moved out to Sea Gate in 1943, Guthrie lived mostly in various apartments in Greenwich Village, including the four communal so-called Almanac Houses, the second of which, at 130 West 10th Street, became the basement home of the Almanacs' famous Sunday hootenannies. Twenty years later, Dylan, too, would bounce around the Village until he moved into his own apartment on West 4th Street. And although there was nothing quite like the Café Wha?, or Gerde's, or the Gaslight for Guthrie or the other Almanacs, one of Guthrie's favorite drinking and singing hangouts, the longshoremen's White House Tavern, six blocks from the last of the Almanac Houses on Hudson Street, would become one of Dylan's hangouts as well. That neighborhood's cityscape had changed hardly at all in twenty years, and neither had a large part of its soul.

All around the city, meanwhile, there was plenty of yesteryear still left for Dylan to see, to touch, and to hold onto. When he wrote his own first songs about New York, Dylan had Guthrie and even Guthrie's New York very much on his mind, because of both it could be said, in Guthrie's phrase, that they "ain't dead yet." "Talking New York Blues," on Dylan's first album, humorously narrates the story of his Manhattan arrival and first days of working in the Village coffee houses. Yet the song pinches a line directly from Guthrie's "Talking Subway Blues," "I swung on to my old guitar," while it tells a bit about a "rocking, reeling, rolling" subway ride by someone who had rambled in "out of the wild west." The song, whose form, of course, comes straight from Guthrie, also quotes—and attributes to "a very great man"—"Pretty Boy Floyd's" fountain pen line, making the tribute explicit. Dylan took the melody for "Hard Times in New York" from the Bently Boys' 1929 recording of "Down on Penny's Farm," but his descriptions seem to owe something to the song about the Rainbow Room that Guthrie called "New York City" in Bound for Glory. It wasn't just Dylan performing as a jukebox—he told his own Manhattan stories by complimenting and amalgamating them with Guthrie's. Imaginatively, New York in 1961 merged easily enough with the New York of 1940.

But of course a lot was different too. The hurtling, bustling, immigrant early 1940s New York had only begun to become not just the greatest city in America but the capital of the twentieth century itself, which it was by the time that Dylan arrived. The Communist left that had provided Guthrie and his friends with gigs and community as well as a cause had become a different kind of subculture, of which the surviving folk crowd was an important element—marginalized by the McCarthyite blacklist and convulsed by the CPUSA's chronic internal crises over the partial revelations about Stalin's terror and the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution and more. Fresh cultural as well as political winds blew across Manhattan, into and out of the Village, including fresh sounds and fresh poetry, some from the famous or soon-to-be famous, some not, some brand new, some very old but collapsing the ancient into the present: "love songs of Allen Ginsberg/an' jail songs of Ray Bremser," Dylan wrote, all mixed up with Modigliani's narrow tunes, the "dead poems" of Dylan's tragic young pal Ed Freeman, Miles Davis's quiet fire, "the sounds of Francois Villon," Johnny Cash's "beat vision," alongside (last but hardly least) "the saintliness of Pete Seeger." Then there was "beautiful Sue"—Suze Rotolo—"the true fortuneteller of my soul."3 And the Beatles were just beginning to happen.

After what he has smilingly called his "crossroads" experience, Dylan had started writing and singing his own fresh sounds. But that left him to reckon with Guthrie, by now relocated from New Jersey to Brooklyn State Hospital. More precisely, Dylan had to reckon with his image of Guthrie. Dylan wrote that Guthrie had swiftly become his last idol "because he was the first idol I'd ever met/face t' face/. . . shatterin' even himself/as an idol"—an auto-iconoclast. The breaking of idols, the recognition that they are only human, normally leads to uncertainty, fear, and a collapse of faith, but with Dylan and Guthrie it was different. In place of the idol, Dylan could see the artist who carried what Dylan called "the book of Man," let him read from it awhile, and thereby taught Dylan what he called "my greatest lesson." Stripped of hero-worship, Dylan's faith in Guthrie's songs abided.4

What lesson Dylan learned, true to form, he did not say directly at the time, although he would say much more over the decades to come. His mind was certainly on idolatry, as young listeners were now beginning to idolize him, thereby causing a menacing press to try and expose him in its own terms and tear him apart with innuendo and rumor, while all along some in the Popular Front folk-singing old guard (and some of their children) were trying to turn him into their own kind of idol, the next Woody Guthrie, the troubadour carrier of their tattered hopes for a brighter political day. Dylan, although keenly ambitious, wanted none of the constraints and destructiveness of this worship: it was enough for him to stand exposed every time he performed in public. As for the incessant questions about how it felt to be an idol—well, after his experience with Woody Guthrie, he wrote, "it'd be silly of me t' answer, wouldn't it. . .?"5

The other lessons had nothing much to do with any cause that Guthrie endorsed—nothing "trivial such as politics," as Dylan would say in his notorious speech to the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee in December 1963.6 (Dylan didn't even think of Guthrie as a political or a "protest" singer: "If he is one," he has recalled, "then so is Sleepy John Estes and Jelly Roll Morton."7) There were the lessons of Guthrie's language—the elegant simplicity of his ballad lines, but also what one reviewer called "the glory hallelujah madness of imagery" in Bound for Glory, which had helped consolidate Dylan's idealization of the man.8 Making those words live, there was the sound of Guthrie's voice "like a stiletto" and "with so much intensity," as Dylan would remember in his memoir Chronicles, along with an effortless diction in which "everything just rolled off his tongue."9

There was the kinetic, usually comedic current in Guthrie's work that leavened his social commentary and his tales of individual struggle and strife. One example: in the early 1940s, Guthrie (with Leadbelly) purposefully turned an old, catchy, and otherwise hard-to-take "nigger in the cornfield" ditty, "You Shall Be Free," into "We Shall Be Free," an extended joke about hypocrite preachers that throws in a sneezing chicken and a wild escape jumping a gully and jumping a rose bush. On his second album, Dylan rendered the same melody as "I Shall Be Free" updating, fracturing, and deepening the joke, poking fun at preaching politicians and television ad madness while rollicking around, one minute getting a phone call from President Kennedy, the next minute chasing a girl in the middle of an air-raid drill, jumping not a rose bush but a fallout shelter, a string bean, a TV dinner, and a shotgun. Two years after that, in "I Shall Be Free #10," Dylan reverted to Guthrie's talking blues form, turned Guthrie's sneezing chicken into a funky dancing monkey with a will of his own, while he commented on leftist-liberal hypocrisy and Cold War paranoia and phony friends in one deadpan joke after another.

Above all, there was Guthrie's direct humanity, especially as captured on Dust Bowl Ballads, recorded for RCA Victor a little more than two months after he hit Manhattan. Guthrie "was a radical," Dylan recalls in the 2005 Martin Scorsese film No Direction Home, which is to say he cut to the quick: "You could listen to his music and learn how to live." Here were stories of men and women confronting psychic as well as physical devastation, beaten to the pulp of permanent homelessness this side of the grave, who somehow mustered the hope to keep moving—hope that Guthrie intended his art to amplify and project. The stories came out of the hungry thirties' Dust Bowl, but their empathy knew no temporal or geographic bounds: they were songs, Dylan writes in Chronicles, which "had the infinite sweep of humanity in them."10

Dylan explained his reckoning with Guthrie elliptically and poetically from the stage of Town Hall in April 1963—and as we reckon with Guthrie on the occasion of his centenary, it is worthwhile considering young Dylan's reckoning of nearly fifty years ago, half the way back. The title of this free verse, "Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie," could not and cannot be taken literally: Dylan may have been putting to rest that night a persona that he had outgrown, but he was not putting to rest thinking about his former idol and the former idol's art.11

It's unclear how familiar Dylan was at the time with Guthrie's script from 1944, "Talking About Songs," in which Guthrie declared his hatred for lyrics that said "you're just/born to lose—bound to lose," that "yer either too old or too young/or too fat or too slim or too ugly or too this or too that," that instead he was out to sing about how, no matter how badly life had knocked you down, "this is/your world."12 But it certainly sounded as if Dylan knew it, as he raced through a myriad of ways in which "your head gets twisted and your mind grows numb/when you think you're too old, too young, too smart or too dumb." Everyone needs hope, he intoned, hope that can't be found in possessions or beauty aids or the lures and snares of celebrity and sex, hope that could be approached two ways: by looking for God at your choice of church or by looking for Woody Guthrie at Brooklyn State Hospital, although both could be found in wondrous natural majesty.

Recalling Woody Guthrie's and Bob Dylan's arrivals in New York deepens an understanding of some of the uproar caused by Dylan's artistic shifts in the mid-1960s. Dylan's supposed betrayal of authenticity and political engagement, which are abstractions, upset a sub-culture that had a lasting presence in New York. Very much alive in 1961, it consisted of people who perceived and even promoted him as a vehicle of their own hope after long seasons of disquiet. When young Dylan resisted and broke away—a gradual process that only culminated at Newport in 1965—he not only shattered illusions; he challenged deep conceptions characteristic of the Popular Front, or of some of its abiding faithful, about what an artist and performer ought to be. "Ought" is a word I've always thought makes Dylan jump; he called into question identifications that were aesthetic and communal as well as political just by being himself.

But Dylan's ambitious rebellion—which to him was a matter of growth—was not the purely destructive act so many perceived it to be. Dylan's lexicon and prayer book are, to be sure, immense, and they include, even inside folk music, far more than the songs of Woody Guthrie, or even of Guthrie's many influences such as the Carter Family. But Guthrie, the former idol, is still very much there as a transcendent force and muse. Listening to Dylan's brand new album, Tempest, I was struck by its concluding elegy to John Lennon, and remarked to no one in particular that Dylan had recorded nothing quite like it since "Song to Woody" fifty years ago. Then to hear Dylan on the rest of the album—re-entering Guthrie's version of "Gypsy Davy" and populating it with his own cast of characters; having his singer-character, on another track, declare, he "ain't dead yet"—makes it plain that, for America's greatest songwriter, the spirit of Guthrie and his music is very much alive within him and without him, like a force of nature to be heard in a rustling wind, glimpsed in a canyon sundown, reflected so that all souls can hear and see it.

Notes

- 1 "For Dave Glover" (1963), a poem that appeared both in the magazine Broadside, issue #35, and in the program for the 1963 Newport Folk Festival. A copy of the Broadside version appears on the blog site "Bob Dylan's Musical Roots," http://bobdylanroots.blogspot.com/2011/02/bob-dylan-songs-in-broadside-magazine.html, accessed 18 December 2012.

- 2 Ibid.; Jon Pareles, "A Wiser Voice Blowin' in the Autumn Wind," The New York Times, 28 September 1997.

- 3 Bob Dylan, "11 Outlined Epitaphs," liner notes to The Times They Are A-Changin', released 10 February 1964, available on the blog site "Beat Patrol," http://beatpatrol.wordpress.com/2010/04/05/bob-dylan-11-outlined-epitaphs-1963, accessed 18 December 2012.

- 4 Ibid.

- 5 Ibid.

- 6 Bob Dylan, "Remarks to the Bill of Rights Dinner, Emergency Civil Liberties Committee", New York, NY, 13 December 1963, transcript available online at http://www.corliss-lamont.org/dylan.htm, accessed 18 December 2012.

- 7 Bob Dylan, Chronicles, Volume One (New York, 2004), 83.

- 8 Horace Reynolds, "A Guitar Busker's Singing Road," New York Times Book Review, 21 March 1943.

- 9 Dylan, Chronicles, 244.

- 10 Ibid.

- 11 Dylan, "Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie" (1963), poem available on bobdylan.com, at http://www.bobdylan.com/us/songs/last-thoughts-woody-guthrie. Recording available on Dylan, The Bootleg Series, Volumes 1-3 (Rare and Unreleased) 1961-1991, released 26 March 1991.

- 12 Woody Guthrie, "Talking About Songs," script for WNEW radio, New York, NY, 3 December 1944, quoted at http://www.woodyguthrie.org/biography/biography3.htm, accessed 18 December 2012.