American Music Review

Vol. XLII, No. 1, Fall 2012

By Raoul Camus

In the 1960s, the centennial of the Civil War inspired a renewed interest in the music of that period, especially performances in military ceremonies, camp duties, and social occasions by the regimental bands and field music. Around this time Frederick Fennell and the Eastman Wind Ensemble brought out two beautifully illustrated and thoroughly documented LPs, one for the Union side, the other for the Confederacy. It was a five-year labor of love. Released on CD in the 1990s, these recordings remain the standard in historically-informed performances of Civil War music.

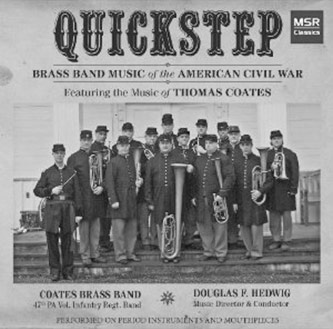

The sesquicentennial has prompted additional Civil War brass bands. We now have the 1st Brigade Wisconsin Band, the 11th North Carolina Regiment Band, the 26th North Carolina Regimental Band, the Federal City Brass Band, the Great Western Band of St. Paul, the 4th Cavalry Regiment Band, and the Dodworth Saxhorn Band, among others. A new group, the Coates Brass Band, has just issued a CD entitled Quickstep: Brass Band Music of the American Civil War. It features the music of Thomas Coates, leader of the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry Regimental Band. Curiously, the enigmatic Coates tried to hide everything about his personal life, including his birthdate and place. Michael O'Connor has done a fine job in tracking down this elusive bandmaster/composer, and has made performance editions of many of Coates's compositions, based on creative historical research.

Quickstep: Brass Band Music of the American Civil War

Military regulations at the time, while limiting regular army bands to two principal musicians and twenty-four musicians for the band, did not regulate the instrumentation of the volunteer bands. Gilmore, for example, had twenty drummers, twelve buglers, and a thirty-six piece mixed wind band in his 24th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Band. On 14 August 1861 Thomas Coates and twentythree musicians enlisted as the band for the 47th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers. Less than a year later, however, General Order 91 directed that all volunteer regimental bands be mustered out of service. While the musicians were offered the opportunity of transferring to the newly authorized brigade bands, none did. Three became company musicians and the other twenty-one presumably returned home to Easton, having served only one year while the regiment continued to serve until January 1866.

"Cottage by the Sea" performed by the Coates Brass Band

The reconstituted Coates Brass Band consists of a director/conductor and fifteen musicians performing on period instruments. The instrumentation is typical for a brass band of the period: three E♭ cornets, two B♭ cornets, three E♭ horns, two B♭ tenor horns, one baritone horn, two basses, snare and bass drum. There was no conductor as such, as the leader normally played the solo E♭ cornet part. The instruments are a mixture of over-the-shoulder, bell front and bell upward. Considering the cost of these instruments in today's market, mainly caused by the renewed interest in this period, this mixture is not surprising, although Dodworth (1853) admonished, "care should be taken to have all the bells one way." The recording session must have been a challenge for the sound technicians. The playing is excellent—quite an achievement by musicians working on unfamiliar instruments. Since they go to so much trouble for authenticity, however, it would have been preferable if the conductor, Douglas Hedwig, an accomplished trumpet player, played one of the cornet parts instead of waving a baton, as indicated in the photo.

The music is typical of what a Civil War band would be expected to perform. The company fifers and drummers would provide the camp duties, and it was up to the band to perform at regimental ceremonies and social occasions. Therefore, their band books would include quick and common step marches, funeral marches, hymns, dances, and concert pieces. O'Connor has made an informed selection, typical of what a bandsman's daily requirements would be. Of the nineteen selections, six are quicksteps, three are patriotic songs, two each of funeral marches, hymns, minstrelsy and concert works, one waltz, one two-step, and one unidentified work, perhaps intended as a quick step. O'Connor might have included a common step march and perhaps more concert works, though that is a minor quibble. More important it would have been very helpful if more information were given about each of the pieces, including sources, other than simply giving titles. For example, since the two-step is normally associated with John Philip Sousa's "Washington Post" and the dance craze that swept Europe and America in the 1890s, how does one explain the inclusion of "Cottage by the Sea Two-Step" in a Civil War band book? Similarly, what do "Turk" and "Phantom" signify?

Military regulations at the time stipulated 110 steps per minute for the quickstep. It was therefore very disappointing to find that none of the selections marked "quickstep" were at that tempo. The closest was the "Cottage by the Sea Two-Step," the others ranging from ninety-two to 106. "Temperance," at ninety-two, is closer to the common step or grand march, which regulations stipulate at ninety. Even the waltz was too slow for that period; a proper tempo would have added a spirited change of pace to the selections.

Despite these criticisms, these musical performances are strong and the research sound. Hopefully the band will continue to bring this important repertoire of 19th century American music to the public through concerts and future recordings.

A Response to "Brass Band Music of the Civil War," by Raoul Camus.

By Douglas F. Hedwig, Brooklyn College

Unfortunately, it appears that Raoul Camus has neglected to consider the internal evidence provided by the music, itself, before assuming that these very unique Quicksteps were intended to be played on the march or used to march troops into position. Certainly we knew that the typical quickstep tempo for marching during the Civil War was 110 beats per minute. However, these works by Thomas Coates are simply not like any other quicksteps written during this period, or later. I believe Coates was clearly an early "American Maverick," perhaps a manifestation of the same impulse that led to the works of Charles Ives, a generation later.

In any case, the degree of harmonic complexity, counterpoint, ornamentation, and overall technical demands of Coates' pieces are so much greater and more technically demanding, when compared to other works of the Quickstep variety during this period, as to virtually ensure that they were never intended for the utilitarian purpose of marching at all. Simply put, virtually no one today could play such difficult music while marching, and certainly not at 110 to 120 beats per minute. Were the players of 150 years so much better than best brass players of today? I don't think so. Indeed, the internal evidence of the music can lead to no other conclusion than that this music was "stylized quickstep;" concert compositions utilizing some of the common style characteristics of the typical quicksteps of the time.

In addition, prior to the recording session, we performed these pieces at 110 beats per minute, and found that the musical richness, wit, cleverness and enjoyment of the works was often lost on many listeners. As regards the use of the term "quickstep" in the titles, evidence leads me to the firm conviction that these were simply entitled "quickstep" for convenience and familiarity, and possibly for potential commercial reasons. Finally, it is important to point out that, like virtually all extant band music from this period, the available source materials for these Coates works contain no metronome markings, nor tempo indications of any kind.

The reviewer implies that military bands typically performed without a conductor during the Civil War, and suggests that our recording should have been performed in a similar fashion. While it is certainly true that the great majority of bands performed their musical duties without a conductor during this period, it is equally true that there were exceptions to this rule when the occasion and/or musical demands required. Again, it is the internal evidence of the music which provides all the justification needed for a conductor on this project. For instance, it is highly unlikely that Coates' beautiful and expressive arrangement of the "Death Song" from "Lucia di Lammermoor" (Track 3 on our recording), could ever have been properly performed (i.e., musically) without a conductor (given its rubato, frequent tempo changes, proper blend and support of soloists), much less by the average band of the time. It is also important to note that using a conductor (myself) to prepare these pieces for modern-day performances and CD recording, allowed for the careful listening, reflection, evaluation and adjustment that is so critical in the re-creation of early music, as well as the efficient use of time during the recording sessions.

In conclusion, after consultation with some of the finest professional brass players in NY, as well as my own extensive research into music of this period, I concluded that these were concert pieces, intended for the entertainment of troops, officers, and the general public, and not for the typical use of the traditional quicksteps in the U.S. Army. As Music Director, Conductor and Producer of this CD, I believe that Coates' unique and virtually unknown music was artistically served by the tempos, performance-practice styles and repertoire chosen, and I stand by those decisions. I encourage all readers to buy or borrow a copy of this recording and decide for themselves.

For more information on this recording: http://www.msrcd.com/catalog/cd/MS1422.