American Music Review

Vol. L, Issue 2, Spring 2021

By Ray Allen

The past year has been one of renewed racial introspection for ethnomusicologists as well as anthropologists and folklorists who study music. I say renewed because these disciplines have long been aware of their colonial roots and the perils of their predominantly white ranks who chronical the music of Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC). But the current climate of racial reckoning has ignited efforts to reexamine the way we go about our research and writing, and to rethink our relationship with musicians with whom we work and how we tell (or help them tell) their stories. In recent years there have been various efforts to address these issues under such banners as collaborative research, reciprocal ethnography, and dialogic editing. These approaches envision projects anchored in partnerships between scholars and musicians that seek to obviate asymmetrical power relations inherent in the traditional researcher/subject hierarchy. Only by empowering the voices of our collaborators, so goes the thinking, can we as scholars begin to dismantle institutional racism and to decolonize knowledge.

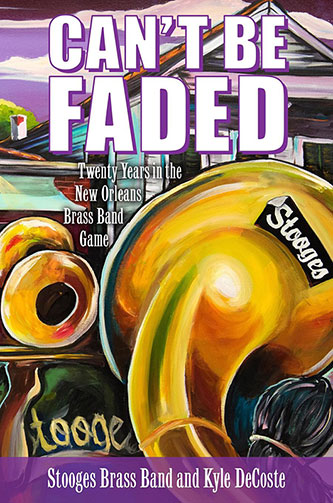

These concerns weigh particularly heavy on white scholars, this reviewer included, who work with African and Afro-diasporic music cultures. In the past decade there have been a handful of noteworthy co-written works that attempt to foreground the voices of musicians from Africa and the Caribbean. I’m thinking of books like Carol Anne Muller and Sathima Bea Benjamin’s Musical Echoes: South African Women Thinking in Jazz (Duke University Press, 2011); Steven Feld’s Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra (Duke University Press, 2012); and Jocelyne Guilbault and Roy Cape’s Ray Cape: A Life on the Calypso and Soca Bandstand (Duke University Press, 2014). But aside from the “as told to” genre of autobiographies such as those by jazz icon Randy Weston (with Willard Jenkins) and R&B legends Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, and the Neville Brothers (with David Ritz), there is little comparable literature on American music. But now enter the Stooges Brass Band and ethnomusicologist Kyle DeCoste with Can’t be Faded: Twenty Years in the New Orleans Brass Band Game (University Press of Mississippi, 2020).

The members of the current Stooges Brass Band are co-authors on this project, which sprang from their desire for a book celebrating their twentieth anniversary (the work would not appear until four years after their twentieth, but no one seemed to mind). Formed in 1996, the Stooges represent New Orleans’s most recent iteration of a venerable marching band tradition that dates back to the mid-nineteenth century. Though perhaps not as heralded as the Dirty Dozen or the Rebirth Brass Bands, the Stooges have been community fixtures in the Crescent City for over two decades, playing regularly for second line parades and funerals, and adding keyboards, guitar, and drum kit for weekly indoor club engagements. As a twenty-first century brass band, they cut their traditional New Orleans jazz with more contemporary sounds of funk, R&B, and hip-hop.

Example 1: “Where Ya From”—It’s About Time (Gruve Music, 2003)

The book’s other co-author, Kyle DeCoste, comes from a very different world. He describes himself as “a thirty-year-old, white, working-class/upwardly mobile, trumpet playing scholar from Nova Scotia” (xiii). At the time of the book’s writing, he was a Ph.D. candidate in ethnomusicology at Columbia University. To his credit, DeCoste recognizes his position of white privilege as “a problematic colonial norm (white researcher/black subjects)” that is “hopefully pushed back against by this collaboration” (232). In that spirit he envisions the project as “an effort at public-facing scholarship” (xiv) that places issues of race and social justice front and center in a work about music and culture.

Can’t be Faded is organized as a joint project between a scholar and musicians. DeCoste introduces each chapter with what he calls “some political/contextual scaffolding” (xiv); that is, he presents sufficient historical information and ethnographic description to make sense of the conversations with band members that follow. His writing in these brief vignettes is lucid and compelling, combining crucial history with rich descriptions of joyful second line street celebrations, steamy club scenes, and the grittiness of life on the road. He doesn’t shy away from controversial issues, reminding readers of the racist policing policies, disproportionate incarceration of Black youth, and post-Katrina gentrification that the band and their fans face daily in the city’s Black, working-class neighborhoods. His commentary is at times provocative but never excessively heavy handed—rather he provides a springboard from which the band members can elaborate.

And elaborate they do, through extended conversations sprinkled with pertinent anecdotes. In the first chapter we meet several of the group’s longtime members, including bandleader and tuba/trombone player Walter “Whoadie” Ramsey, trombonist Andrew “Drew” Baham, and saxophonist/music educator Virgil Tiller. They reminisce on how the band first came together through the merger of marching band players from two New Orleans rival high schools. They credit the training they received in their school bands for providing the firm musical foundation and sense of discipline that proved invaluable in pursuing their careers as working musicians. As their stories unfold, we learn that the Stooges are more than a music unit. The band also functions as a sort of fraternal brotherhood, offering young Black men an alternative to the perils of street gang life, as well as an economic enterprise to provide a living for the members and their families. Some of the band’s early proceeds went toward the purchase of several floors in a large apartment building. In what turned out to be an experiment in communal capitalism, they transformed it into the Livin Swell Recording Studios that doubled as office and rehearsal space. “The Stooges are run like a business,” declares bandleader Walter, and one that demands time, discipline, and dedication.

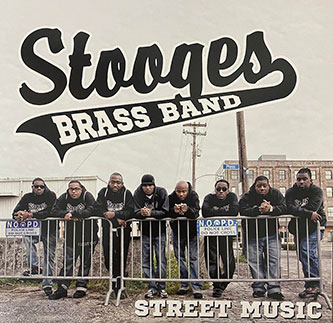

Throughout the book various band members reveal the vicissitudes of brass band life. There are those transcendent moments when they “wind it up” with fans at local clubs like the Well and the Hi Lo Lounge, and when they commune with neighbors at second line parades and social aide gatherings. They recall with pride their excitement in winning the 2010 Red Bull Street King brass band competition and of producing their three main recordings: It’s About Time (2003), Street Music (2013), and Thursday Night House Party (2016). And they take great satisfaction in knowing that the weekly music instruction classes that their senior members run at the Livin Swell compound are passing on the tradition to a younger generation of soon-to-be brass band players.

Fortunately, the Stooges and DeCoste resist the temptation to overly romanticize the brass band experience. The endless labor needed to eke out a living as a musician is a frequent theme. They recount a typical Saturday when the band spends hours in the heat of a second line parade, then runs to several “black and white” wedding gigs, and completes the day with one or more evening club appearances. With many members now in or approaching their forties, the intense physicality of the job has begun to take its toll, as described in chapters devoted to the toil of working the local club circuit and the grind of summer touring in old vans prone to late night Interstate breakdowns.

Added to these routine daily challenges was the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. In response to the collapse of the city’s economic and cultural infrastructure, the band split apart, only to regroup when Walter returned from Atlanta two years later. This was a turning point for the band. Out of necessity the Stooges expanded their outfit to include an indoor stage band with drum kit, keyboards, and guitars to complement their traditional street band configuration.

The most chilling chapter in the Stooges’ story bears the title of one of their original and most poignant songs, “Why They Had to Kill Him?” (Example 2). The piece is a tribute to one of the band’s ex-members, twenty-two-year-old trombonist “Little Joe” Williams. He was, ironically, on his way to play a funeral gig when he was stopped by the New Orleans Police for driving a stolen truck (the family claimed it was borrowed). As he was getting out of the vehicle and reaching for his trombone case, someone apparently yelled “gun” (he was in fact unarmed), and he was riddled with twenty-one bullets by three police officers. The song lyrics and the band members’ recollections are solemn reminders of the racist policing that was, and remains, a systemic issue in New Orleans’s Black neighborhoods. This should give present-day readers pause as they process the sad reality that this now-too-familiar scene took place more than a decade ago, years before we knew the names Michael Brown, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, or George Floyd.

Example 2: “Why They Had to Kill Him?”—5 May 2016 at the Hi-Ho Lounge, New Orleans

As compelling as many of these individual stories are, parts of the book are not totally cohesive, and a few areas cry out for further commentary. The band members’ dialogues sometimes wander, resulting in the occasional unwinding of their narrative threads. What is also lacking is more discussion the band’s informal head arrangements. How do they balance melodic themes, riffing sections, and individual solo improvisations? What makes a good brass band arrangement, and a moving solo? And how does the band merge elements of contemporary R&B and hip hop with older funk and traditional jazz styles? These are not always easy concepts to put into words, but readers would benefit from hearing the Stooges expound in more detail about their music.

My other concern is the absence of any discussion of gender. The dozens of players whose stories form the core narrative of the book are all men. I understand that the brass band world is a male one, and, as DeCoste points out, the band affords young Black men the opportunity to gain a modicum of respect and economic independence that American culture too often denies them. Yet one cannot help but ask, “Where are the women?” Is this absence a result of early gender-instrument profiling back in middle and high school—adherence to the old trope that horns and drums are not for girls (this way to the flutes and glockenspiels ladies)? Does the current Stooges mission to teach young aspiring musicians extend to the recruitment of young women? These questions need to be asked.

These minor quibbles aside, Can’t be Faded is, by every measure, an exemplary collaboration between the Stooges and DeCoste. Together they take us deep into the worlds, and indeed the heads, of New Orleans brass band musicians. Yet by his own admission, DeCoste had a strong hand in shaping and editing the narrative, so the specter of the white interlocuter never fully disappears. This begs the question of how the story might have differed if told by a Black co-author, perhaps a New Orleans-based insider? This is an unknown that will probably remain unknowable. But here’s what we do know. There is no shortage of talented Black musicians in New Orleans, and for that matter across the United States (yes, Brooklyn’s in the house), who probably never will make the media spotlight. Their stories need to be told in the name of cultural equity, social justice, and the celebration of art. To see that this history is presented from a variety of perspectives we need to encourage, and our institutions must support and hire, more BIPOC researchers and writers. This doesn’t mean that white writers shouldn’t be part of the mix, but if they are, they should take a lesson from DeCoste and the Stooges: more collaboration leads to more empowerment and more information being made available to diverse audiences.

Some readers may question if this sort of collaborative writing belongs on a University Press. After all, more than half of the text consists of spoken dialogue between lay musicians with little formal writing experience, rather than the carefully researched and well-polished expository prose of a professional scholar. A related issue is whether such co-authored works should count when scholars go up for tenure or promotion at their academic institutions. On both counts let me respond with a resounding “Hell yes!” If university presses and university music departments are ever going to break out of their myopic disciplinary bubbles and academic silos, and if they are ever going to seriously address issues of racial justice, they need to bring more diverse voices to the table and to reach out to broader audiences. Or, as Stooges’ trumpeter Al Grove remarked to DeCoste early on in the project, “it would be nice for all of us to be able to go up and show our grandkids a book of our story.” To that trombonist Drew Baham’s added that the book should also include “some sort of social commentary” regarding the broader struggles facing band and their community (xiv).

We should applaud the efforts of the Stooges, Kyle DeCoste, and the University of Mississippi Press for bringing this work forward. Such co-authored biographies are one small step forward in the larger project of decolonizing knowledge and standing against institutional racism. And to the Stooges, happy belated anniversary!