American Music Review

Vol. XLIX, Issue 2, Spring 2020

By Will Fulton

In the ever-changing cityscape of Brooklyn, little evidence remains on the streets of the vibrant early years of hip hop culture that existed in 1980s. Though a significant culprit may be gentrification, part of the reason for the absence stems from the ephemeral nature of the music business itself. The sites of that industry—recording studios, record companies, record stores, and nightclubs—have only occasionally survived through civic support or been considered landmarks. Further, often due to the increasingly high cost of living and changing demographics in the borough’s once-predominantly African American neighborhoods, many of the participant rappers, deejays, producers, and promoters in the early days of Brooklyn hip hop culture have since moved away.

While the cultural sites that supported hip hop music in its early years all but disappeared in some borough neighborhoods, the records produced by Brooklyn rap soloists and groups in the 1980s capture the borough’s critical contributions to hip hop’s vibrant first decades. Long before the images of hip hop stars were used to elevate Brooklyn’s cultural cache during city-sponsored urban development projects like Forest City Ratner, local performers such as Audio Two and rappers such as MC Lyte (Lana Moorer) were producing recordings that captivated the city. Collectively they employed innovative techniques that redefined what was possible in hip hop, and mainstream music in general. Their locally-produced records stand as sonic reminders of the importance of DIY production at a critical period in the history of hip hop.

During this era, 12” singles served as both the primary mode of transmission and sonic artifact of hip hop culture. They reflected a distinct mode of cultural production, and their legacy with local hip hop fans was reinforced every time the record was played by a deejay on the radio, at the club, or block party. These events were then memorialized on homemade cassettes that teenagers commonly traded for boombox or headphone listening. The success of a hip hop record could be judged by the number of times it was heard coming out of cars or radio speakers, and the speed that fans memorized and recited the lyrics.

Given this history, understanding how these records were conceived, produced, sold, distributed, and received is critical to understanding local hip hop culture. A prime example is the story of the First Priority Music label, a Brooklyn-based independent label run by former club promoter Nat Robinson with his teenage sons Kirk Robinson (Milk Dee) and Nat Robinson Jr. (Gizmo), who recorded as Audio Two. Their struggles and accomplishments exemplify how Brooklyn entrepreneurs (often before they turned eighteen) redefined what was possible in the music industry.

Kirk chose “Milk Dee” as his rap name in the fifth grade, and recalls his classmates laughing at him when he arrived on the bus wearing a windbreaker with a custom emblem bearing the name in 1981. Later, while attending Brooklyn Technical High School with his friend and neighbor King of Chill, who had a group called the Alliance of MCs, Milk recalled: “We both lived in Bed Stuy, I lived on Halsey, and [King of Chill] lived on Sterling, and his DJ lived near there. And at that point, we met, and me and Giz[mo] would go over to his DJ’s house, and we would rhyme, and we were making routines, like [Bronx pioneers] the Cold Crush [Brothers]. And we became friends.”1

Their early attempts convinced them both that they should have their own record label and their own recording equipment. Milk eventually persuaded his father to invest in the project. He and his brother, Gizmo, made their first recording as Audio Two in 1985 for MCM Records, a label run by a club promoter friend of their father. Milk recalls that they “went into the studio, and they had an MCI board, thirty-six tracks, we were recording on twenty-four tracks. After doing that record, that’s when I decided, like ‘Yo, I could be a producer, I want to make the beat myself.’”2 Meanwhile his father, Nat Robinson, using the MCM label and services but paying all the bills himself, decided, “we might as well start our own label.”3 In addition, he wanted to find a way to cut down on the high recording studio costs by buying home recording equipment: “We’re paying all this money per hour, and we’re not professionals, so we’re spending like crazy hours. We’re getting into a thousand dollars for one song! So at that point, Milk says ‘I want to experiment more,’ and we gave him the four-track [recorder].”4

After their parents’ divorce, the Robinson sons moved in with their father, leaving Bed Stuy for Staten Island, and setting up a studio in the basement with a cassette-based Tascam 246 four-track cassette recorder, two Roland drum machines (a 707 and a 727), and a Boss sampling delay guitar pedal. While contemporaneous digital samplers were too expensive for the fledgling producers, using the guitar pedal was an ingenious, inexpensive workaround. The Robinsons connected with local Brooklyn celebrity DJ Cutmaster DC who, following a recent success with his “Brooklyn’s in the House” single, had also relocated to Staten Island. DC helped them set up the studio, but Milk remembers everyone telling him “you can’t do a record on a four-track!” But “the more they kept sayin’ it, the more determined my father was for us to do songs on the four-track.”5

While Milk’s makeshift studio was downstairs, his father set up a makeshift record label office upstairs crowded with records, as he describes:

The First Priority office was in my home in the beginning, we were working out of the house. So all the boys, when you’d eat your dinner, ‘cause you know you had wax in those days. So we had so many records coming in from all parts, different manufacturers, and we had them in the house. So what we had to do, our dining room, our living room was just completely full of boxes of records. So the guys used to pile four boxes of records on top of each other, and at dinner time, you’d get yourself a chair and you get four boxes of records and you’d put your plate on top of the records.6

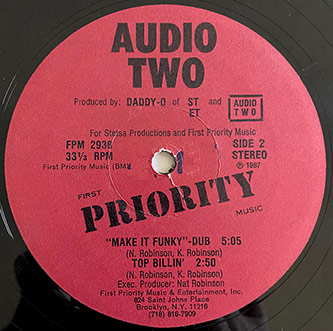

When the first Audio Two/Alliance EP failed to gain traction in 1986, Milk, his brother Gizmo, and their friends continued to experiment with new songs in his home studio on the cassette-based four-track machine. Meanwhile, his father relocated the newly christened First Priority Music to a storefront at 824 St. Johns Place, on the corner of Nostrand Avenue in Brooklyn.

Milk had met Brooklyn rapper Daddy-O of Stetsasonic at a local studio while recording their first records. Nat Robinson was impressed and soon enlisted Daddy-O to help with his kids’ productions and his fledgling label. The collaboration would soon prove fruitful. Milk recalled the evening when he introduced Daddy-O to his off-kilter rearrangement of the Honey Drippers’ “Impeach The President,” which featured a funky introductory drumbeat that was popular with rappers, and would provide the instrumental track for the group’s “Top Billin’”:

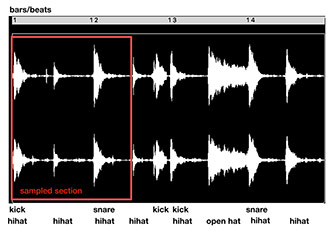

And that night (in my basement), I came up with the beat for “Top Billin’,” I liked it, put the rhyme down, that song took a total of thirty minutes. The guitar pedal only allows you to record two seconds. And, that’s it. And that’s why, with “Impeach,” it’s just kick, hat, snare. That’s all that would fit into the pedal. Every time the kick hits, it plays the kick, hi-hat and snare, unless I cut it off with another kick.7

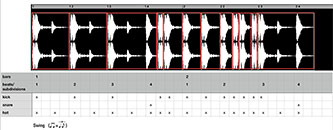

Figure 1 shows the opening drums of the Honeydrippers’ “Impeach The President,” outlining the section sampled in “Top Billin’.” Figure 2 shows the arrangement of samples triggered in “Top Billin’.” Note that the audio waveform is significantly altered due to low-resolution sampling in the guitar pedal. In the early days of hip hop sampling, influenced by the technical limitations of the guitar pedal sampler, Milk had created something quite original: a stuttered, atomized version of a popular drumbeat with a rhythmic pattern that shifted from measure to measure. The low-resolution guitar pedal sample and the offbeat reconfiguration of the “Impeach The President” drums, coupled with Milk’s high pitched voice, made “Top Billin’” a highly unusual track. To this, Daddy-O added a vocal sample from his recent 12” single to highlight the borough, and felt they had something special:

We grabbed the “Go Brooklyn!” [chant] ‘cause we got a thing called “Go Brooklyn” on the [Stetsasonic] “Go Stetsa” 12. So we [sampled] a little bit of that “Go Brooklyn.” I said, “this is gonna be a big [DJ] Red Alert record!”8

They pressed the record, with “Top Billin’” as the B-side. But DJ Red Alert, then the most influential hip hop DJ in New York, wouldn’t play it. For months, Audio Two’s “Make It Funky”/“Top Billin’” single found few supporters. The family went to work promoting from the First Priority office on St. Johns Ave in Brooklyn. But it was slow going. Milk recalls:

When we released “Top Billin’” every DJ that we sent it to said it was wack. They said “Top Billin’” was wack. [They said] ‘He sounds like a girl!’ It took us a year, of constant work, we were sending out records every day. My father pressed 50,000 records. The people at the post office, when they would see us comin’ they would just let us in the back. And I’m talking about typing up the labels individually on a typewriter, putting the records in an envelope with an insert. We had boxes of the records in the car, and we were driving around to record stores, tryin’ to get them to put the records in the stores.9

The Robinsons had little knowledge of how to proceed with their records. For distribution of their initial pressings, they relied on two local Brooklyn record stores, Birdel’s on Nostrand Avenue and Soul Shack on Pitkin Avenue, which served the Black community and had recently incorporated a section for rap records. Eventually their efforts with these and other Mom and Pop record stores paid off.

When record distribution became overwhelming for the family-run label, Nat Robinson took his records to Pearl One Stop, a record distributor on 20th Street in Brooklyn that agreed to distribute it to local stores for a per-record fee. One-stop distributors like Pearl were an essential part of independent music business network in New York, working with independent record labels to distribute smaller shipments to stores than would be of interest to major distributors. But even with city-wide distribution, the record still struggled to find an audience. For then sixteen-year-old rapper-producer Milk, the seeming failure of the single that featured both his solo rapping and production was heartbreaking.

I used to cry. There were times that I would hear that “Top Billin’” was wack so much that I would cry! I would come home, and I’d be so hurt, and I’d cry, then I’d get myself together, and I’ll be like, “I’ll show them.” It took us a whole year of that, every day, before we found one DJ that was like, “this is dope.”10

Undaunted, Nat Robinson continued to push the record and eventually things began to shift:

I started calling all the college DJs, and sending everything out, and there was a guy named Jeff Foss, at that college out in Long Island [WHRU - Hofstra]. He was the first guy that started playing the record on the radio. I would give Red [Alert] a record every time I saw him. So I got [DJ] Marley [Marl] and Marley started playing it, and he loved it. So I got Marley to play it, I got Chuck Chillout to play it. So I had Jeff Foss, Marley Marl, Chuck Chillout, and Teddy Ted and those guys playing it [on their popular radio shows]. ... And then “Top Billin’” started getting a little momentum with these guys playin’ “Top Billin’.” So I reissued the record, and I made “Top Billin’” the A-side. And I put it back out again. Just “Top Billin” [with a remix]. So we hit the streets again. So one day, I’m walking down the street in New York, and somebody comes past with a car, [with the song’s lyrics] “Boom Boom - Milk Is Chillin!” I’m like, “Wow, they playin’ in the car.” I go a few more blocks, I’m walking somewhere. “Boom, boom.” Another car. I’m thinking, “This is happening, the kids are playing this song, they’re playing it!”11

Soon, the record, a 12” single B-side recorded on a cassette four-track in a basement studio and released on a tiny independent label run out of a Brooklyn storefront was the #1 requested record on WKRS-FM. At the same time, First Priority started to gain traction with another single by a sixteen-year old Brooklynite, the recently named MC Lyte [Lana Moorer].

MC Lyte’s recording career started in a Brooklyn home studio. She recalls that the “first time she recorded” a demo of her initial single, “I Cram to Understand U,” was at “Tony’s studio in Brooklyn.”12 He knew her as Lana, she knew him as Tony, but he would soon be known as DJ Clark Kent, and become a key proponent in the careers of Notorious B.I.G., Jay-Z, and others. Clark Kent recalls that the two “were at Union Square [club] until four in the morning, and then after we went to my house and I made a beat on a DX drum machine. I made the beat for her, it wasn’t the record, it was just a beat for her to do it in my crib, at like five in the morning after playing at Union Square.”13 Lyte played the demo for her friend Eric Cole of First Priority group The Alliance, and shortly after, she was re-recording “I Cram to Understand You” on the Robinson’s Tascam four-track to a Milk Dee-produced track.

In 1987, promoting both singles from their storefront office on St. Johns in Brooklyn, First Priority had to overcome resistance. If people initially dissed Milk for sounding “like a girl” on “Top Billin’,” the response was similar for gravel-voiced Lyte: “She sounds like a boy!”14

But as “Top Billin’” started gaining national success, Larry Yasgar and Sylvia Rhone of Atlantic Records took notice, and offered Nat Robinson a distribution deal for First Priority Music. Within a year of her first single, MC Lyte would be the label’s star performer. “Top Billin’” had crested its yearlong wave from being a humble local record to receiving national acceptance, while “I Cram To Understand You” had introduced MC Lyte. Once struggling to get their independent records played, First Priority now had Atlantic Records’ backing and an avenue for the label’s creative output, which by 1988 increasingly centered on the success of eighteen-year-old MC Lyte. With Audio Two, Alliance, and Lyte all releasing albums in 1988, as well as a compilation and singles by Bronx rapper Positive K, First Priority had turned the enthusiasm of two teenaged brothers and their friends, and their new star performer MC Lyte, along with their dad’s business acumen, into a successful Brooklyn record label with nationally-charting records.

Although the label had major backing, the record production in the early years continued to center on tracks developed in the Robinson basement or at King of Chill’s family’s apartment on Sterling Avenue. There was no major label representative to mediate the creative process. Rather, if Milk, Chill, Lyte, Giz, and their high school friends thought a song was “hot,” they pursued it. And since no one had initially believed in “Top Billin’” or Lyte’s first single, Milk was disinclined to listen to outside opinions. Meanwhile, most of the lyrics for Lyte’s debut album came from her rhyme book that she wrote in her early teen years: “With recording the first album I just showed up with my rhyme book. Literally, Milk and Giz were like ‘What you got?’”15

One of the songs in Lyte’s book would become her breakout 1988 single, “Paper Thin,” written about an unfaithful partner before she had even been in a relationship. Alliance’s King of Chill crafted the track for her rhyme, with short sampled fragments of Prince’s “17 Days” and Al Green’s “I’m So Glad You’re Mine.” The initial work was done in Chill’s family’s apartment on Sterling Avenue with his Alesis drum machine, and followed by mixing at Firehouse Studio in Brooklyn Heights. For producer Chill, the success of “Paper Thin,” from his apartment to the clubs, TV screens, and national chart success was a “dream come true” in their journey:

The goal when you start rappin’ is to be the coolest dude on your block and in the neighborhood. But after a while, you tryin’ to be heard in the clubs that you frequent, which is Latin Quarter, Union Square, Rooftop, places like that. At the point to now we can hand the record to the deejay, and it’s not a hassle for them to play it. You couldn’t be nobody and hand the record to the deejay. So we get to “Paper Thin,” and he puts it on, and it’s just lightin’ up the dance floor, that was the greatest thing! Not only that, we had a video to support it on [local cable rap show] Video Music Box, which was our MTV, that was the greatest.16

The video—filmed on a subway car at the New York Transit Museum in Downtown Brooklyn—includes Lyte, Audio Two, and many of their friends, and serves as a document of their youthful creative works and locally produced success story.

MC Lyte, Audio Two, and King of Chill’s group Alliance each released their debut albums in 1988, before Lyte had even turned eighteen. First Priority now had major label backing but was still driven by singles written and recorded in Brooklyn apartments and Staten Island home studios, as well as local studios like Firehouse. Within a year, the company had become a successful local record label, with the help of other local Brooklyn businesses, including Soul Shack and Birdel’s record stores, Pearl One Stop, and Firehouse. The crew of friends that had formed at Brooklyn Tech were now touring nationally in support of their largely homemade records made with the assistance of other Brooklyn rap pioneers DJ Cutmaster DC, DJ Clark Kent, and Daddy-O of Stetsasonic.

Most of the Brooklyn locales integral to the early history of First Priority Music—the record label office on St. Johns Place, Soul Shack on Pitkin Avenue, Birdel’s Records on Nostrand, Pearl One Stop record distributors on 20th Street, and Firehouse Studios on Dean Street—are long gone. While Birdel’s, a fixture in the community for forty-five years before closing in 2011, has been commemorated with a street sign on a section of Nostrand Avenue, the rest are simply facts of history, known only to those who experienced the vibrant local culture of Brooklyn hip hop in the 1980s.

(L-R): MC Lyte and Milk Dee of Audio Two performing at Coney Island Ampitheater, June 20, 2018, screen captures from Big Daddy Kane: Long Live the Kane 30th Anniversary

At a 2018 concert at the Coney Island Ampitheater celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of his debut album, Big Daddy Kane brought out a series of Brooklyn performers who made their name in the 1980s, including First Priority Music’s MC Lyte and Milk Dee of Audio Two. Both Lyte and Milk were celebrating the thirtieth anniversaries of their debut albums as well. The two local legends were received enthusiastically by the crowd of five thousand, many of whom were in their forties and fifties and had grown up in the local hip hop scene. When Milk Dee rapped “Top Billin’,” most of the crowd rapped along with the lyrics word-for-word, the song serving as a document both of their youthful memories and a testament to the local DIY hip hop culture of the 1980s.

Riding home from the concert on the subway, I sat next to a woman who reported that she had a cousin in local hip hop group Divine Sounds, and while in high school, she visited the First Priority offices on St. Johns Place and interviewed Audio Two for her high school newspaper. For her and many in attendance, these local sites of hip hop culture were an important part of the Brooklyn they grew up in. Although the borough has changed, the records of performers such as Audio Two and MC Lyte serve as reminders of this vibrant local Brooklyn scene in the 1980s, when a high school kid’s dream was to be “Top Billin’” at a local rap show.

Notes

- 1 Milk Dee [Kirk Robinson] interview by author, 7 March 2019.

- 2 Ibid.

- 3 Nat Robinson interview by author, 20 February 2019.

- 4 Ibid.

- 5 Milk Dee interview.

- 6 Robinson interview.

- 7 Milk Dee interview.

- 8 Daddy-O [Glenn Bolton] interview by author, 27 November 2018.

- 9 Milk Dee interview.

- 10 Ibid.

- 11 Robinson interview.

- 12 MC Lyte quoted in Keith Murphy, “Full Clip: MC Lyte Breaks Down Her Entire Catalogue (Brandy, Janet Jackson, LL Cool J & More),” Vibe, 7 January 2011.

- 13 Clark Kent [Rodolfo Franklin], interview by author, 8 March 2019.

- 14 Milk Dee interview.

- 15 Lyte quoted in Vibe.

- 16 King of Chill interview by author, 22 February 2019.

![Milk Dee’s Tascam 246 four-track recorder, photo courtesy of Milk Dee [Kirk Robinson]](/web/aca_centers_hitchcock/AMR_49-2_Fulton_3_333x292.jpg)

![1987 promotional flyer for MC Lyte’s first single, distributed from the First Priority office, courtesy of Milk Dee [Kirk Robinson]](/web/aca_centers_hitchcock/AMR_49-2_Fulton_6_333x456.jpg)