American Music Review

Vol. XLVII, Issue 2, Spring 2018

By Paula Harper, Columbia University

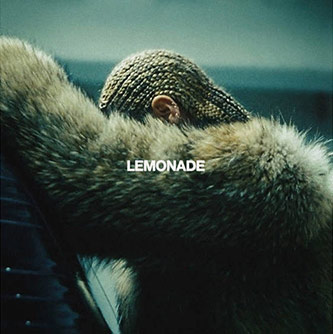

Like so many of her actions and performances across the 2010s, Beyoncé’s 2016 visual album Lemonade seemed to compel response—an ocean of tweets, a deluge of think pieces. As a visual album, Lemonade is a bold political treatise. It’s a dreamy, poetic fantasy. It’s a dense tapestry showcasing the power and beauty of myriad forms of black womanhood; it weaves together afrodiasporic identities, traditions, images, sounds, spirituality, stories. It flows nimbly through genres, from gospel and trap to country and rock. This exploration is a kind of history-making too, a reminding and a reclaiming of sonic space alongside guitars, harmonicas, drum kits—a reminder that country and rock have their roots in black creativity and cultural production. Lemonade blurs the universal and the unique, the personal and the collective.

This brief article catalogs a few of my responses to Lemonade—in particular, my response to a moment in the track “Sandcastles.” On my first encounter with the album, my breath caught at a striking moment in the second verse, a point of what seemed like weakness or fracture, a break in Beyoncé’s celebratedly virtuosic voice.

Dishes smashed on the counter

From our last encounter.

Bitch, I snatched out the frame.

Bitch, I scratched out your name

And your face.

What is it about you

That I can’t erase?

For me, the moment of vocal break in “Sandcastles” instigated a site of heightened sonic and affective engagement, via the medium of voice. But I contend that the visual framing of “Sandcastles” within the Lemonade visual album disrupts an easy collapsing of this moment into a single, accessible emotional affiliation between a viewer-listener and Beyoncé. Instead, by foregrounding Beyoncé’s workmanship and real-life labor as a singer and artist, “Sandcastles” opens up multiple avenues for reading the song and larger project, particularly in terms of claims about gender, race, and agency.

“Sandcastles”

Much of the Lemonade visual album is a dreamscape, or a fantasy. Beyoncé floats through a flooded bedroom of poetry and voice, ruminating on the glories and revulsions wrought on and through the female body. She is birthed glorious and enraged. She is a goddess, a bandleader, a priestess, moving in slow motion through fire and water, knitting together dances as unexpected rituals, filled with haunting, sometimes familiar, faces.

Released in April 2016, Lemonade followed the 2013 release of the self-titled album BEYONCÉ, the wildly successful surprise visual album that achieved massive sales without any prior industry promotion. Like BEYONCÉ, Lemonade came packaged as both audio and visual tracks; twelve singles woven together into an hour-long movie, sutured via the poetry of Somali-British poet Warsan Shire, read aloud as voiceover by Beyoncé. If the 2013 visual album cohered around themes of Beyoncé’s biography, her role as a musician, wife, and mother, and variegated expressions of her sexuality, the 2016 follow-up centered around the experiences of black women more broadly. The album also was seen to aestheticize Knowles-Carter family drama; the album was initially launched as a live special on HBO, and fans watching in real-time were quick to interpret the album as a specific confirmation and denunciation of Jay-Z’s infidelity to Beyoncé, which had been a subject of periodic tabloid conjecture for years throughout the 2010s. Fans speculated on social media that the Lemonade premiere might have been serving as an audiovisual divorce announcement. Ultimately, though, titles superimposed across the film tracked a trajectory from indictment to pardon: from intuition, denial, anger, to forgiveness, resurrection, hope, redemption.

The song “Sandcastles” comes at the pivotal turning point in this trajectory—“Forgiveness”—with lyrics that speak of the pain of failed relationships; the song opens “We built sandcastles that washed away,” and a recurring refrain laments that “Every promise don’t work out that way.” As a viewer I might have expected to see an angry, bitter, or impassioned Beyoncé—I would have anticipated that her body’s outward appearance conform to the striking and audible fault in her voice, the rasp and almost-scream suggesting a surfeit of emotion, an excess, a loss of control. The actual visual for “Sandcastles,” however, surpasses and complicates these expected images. The section of the Lemonade film entitled “Forgiveness” begins—and indeed, the viewer is at the water.

This is the dream world of Lemonade—all black and white, slowly panning through trees covered in Spanish moss, intercut with shots of a mesh-shrouded Beyoncé lying on a beach, just touched by languid ripples of the water’s edge.

Despite the suggestion of the title, the dreamy shore is precisely what’s left behind in the transition to the song “Sandcastles” itself. The film moves from outdoor settings to the interior of a domestic space, and shifts from black-and-white to color. The diegetic sound shifts too, from the buggy chirps and whistles of the south in the summertime, to the crackle of a fir e and a familiar record, off in the distance—Nina Simone’s “The Look of Love.” Then, as “Sandcastles” begins in earnest, these diegetic domestic sounds are silenced and a piano track starts. Beyoncé sits surrounded by the contemporary electronic accoutrements of her profession—a keyboard, a laptop, headphone s and a pop filter.

The viewer sees Beyoncé—not enraged, not perturbed, not even within the world of the song’s textual narrative. Instead, she’s focused, hard at work at the craft of producing contemporary pop music—this music, the music we as listeners and viewers are consuming. As the song progresses, the video’s narrative shifts away from this focus, moving to imagery that’s perhaps more expected—shots of a seemingly pained Beyoncé, close-ups of her face, intimate, mirrored inter actions between her and her husband Jay-Z.

But that first shot of Beyoncé-as-recording-musician sticks, and it re-writes a simple understanding of what might otherwise have been understood as sincere vocal failure. Let me return to the voice, then— Beyoncé’s voice as it breaks over the words “your face” and “what is it about you.” As she slides up to the first b-flat of “what” in full chest voice. As she flips to head voice when she pops up to it again to end t he phrase on “you.” As instead of clear tone and pitch she rasps, we hear the grain of her throat, the constriction of her vocal cords. It’s visceral, it’s affective, it wrenches attention to the materiality of Beyoncé’s body, and forges a connection between that body and the body of her listener.

Voice

In thinking of the voice as a powerful medium or conduit, I’m connecting myself to a whole line of scholarship, on voice broadly and on popular music and Beyoncé more specifically. Steven Connor frames voice as a paradox, a production emanating from a specific body , but an entity separate from the uttering body in its utterance. Connor’s term vocalic space encompasses “the ways in which the voice is held both to operate in, and itself to articulate, different conceptions of space, as well as to enact the different relations between the body, community, time, and divinity.”1 The voice takes up space, extends the body—Beyoncé is distributed out to her listeners, her voice mediated by the modern technologies of sound reproduction and amplification.

Listening specifically to Beyoncé, Regina Bradley has suggested how sound and voice offer areas of slippage for Beyoncé to navigate and undercut otherwise binding tropes of race and gender expectations.2 Additionally, Bradley theorizes what she terms a sonic pleasure politics, in which she argues for a “need to recognize sound as a reservoir of pleasure, raunchiness, and sexual work” and suggests ways in which layers of signification might offer avenues of agency.3 Robin James has similarly suggested ways in which black female musicians “use extra-verbal vocal sounds to re-script gendered bodily pleasure.”4 These scholars draw parallels to the work of Ashton Crawley and Shakira Holt, connecting black female pop and hip hop vocalizations to soundmaking traditions of black praise and Pentacostal singing, noisemaking, breathing.5

Much of this scholarship on voice explicitly connects voice and pleasure as a conduit within the performer who produces sounds through her voice, both distinctly her own and distinct enough that she can experience them as pleasurable in her own body. But there’s also a relationship that extends from the performer, through the voice, to the listener. As Connor suggests: “When we hear a song that we enjoy, we find it hard not to sing along, seeking to take it into our own bodies, mirroring and protracting its auditory pleasure with the associated tactile and propriocentric pleasures.”6

So in thinking this way about voice, I’m also threading through my own situated and embodied responses to this music and album. Beyoncé’s voice extends from her to me, through my headphones or the speakers in my car, vibrating into, over, and through my body. Imagining what it would be to sing the words and pitches (or perhaps not imagining, perhaps indeed singing), I re-sound her voice in my own chest and throat and face. I feel the sound break across my palate and through my nasal cavities. Francesca Royster reminds me that “Throats are part of the erotic act, commanding, whispering, swallowing.”7 As I listen to Beyoncé sing “Sandcastles,” I think about my throat closing with tears, or wracked in the aftermath of sobs and screaming.

“Rocket”

Though it features an entirely different manifestation of Beyoncé’s voice, I hear the song “Rocket,” from the 2013 self-titled visual album, as an important precursor to the peculiar alignment of voice and visual narrative in “Sandcastles.” “Rocket” is arguably the most explicitly sexual song on that album—a-feat, considering that the album was widely discussed for its frank musical, lyrical, and visual depictions of sex and sensuality. “Rocket” is a sonic map of an act of sex, of lovemaking. Beyoncé’s vocal techniques alternate between growls and breathy head voice croons; often, a dense choir of overdubbed Beyoncés sing in close harmony, with synchronized, overlapping melismatic fills atop a base of sinuous electric guitar and a languorous drumbeat. While the audio track features a relatively standard pop song form, the visual album’s video version more explicitly suggests the trajectory of a sex act—ending abruptly after the shattered, shimmering vocals and quick-cut, overlapping images of the bridge’s climax. In a behind-the-scenes video from the album, Beyoncé describes the song as having the contour of a sexual act, but she also characterizes it as being “about singing...harmonies, and ad-libs, and arrangements.”8 Musical labor is blurred with—acknowledged as—bodily pleasure.

Moments in the “Rocket” video’s visual layer similarly suggest this departure or complication. Alongside and in between the concupiscent images that make up most of the video—slow motion, extended shots that linger on Beyoncé’s curves—are more anodyne ones: Beyoncé on a bed surrounded by sheets of paper; Beyoncé at a piano, her back to the camera. If the former thread of shots situate the viewer in the fantasy position of a familiar lover, these latter images catch Beyoncé in a different productive act, that of songwriting and music-making. Like in “Sandcastles,” the “Rocket” video complicates a straightforward musical interpretation by interrupting the audiovisual space with a glimpse behind the scenes—even as that glimpse itself is unambiguously framed as artificial and highly-produced, wrapped in the same filmic aesthetics as the music video narrative surrounding or interspersed with it.

It is a common strategy in the framing and editing of music videos to encourage identification of the singer/performer figure with that of the protagonist of t he music video’s narrative, augmenting extant tendencies to autobiographically attribute the narrative or emotive content of a popular song to its singer (and perceived author figure). I argue that “Sandcastles” and “Rocket” offer interruptions to these layered affiliations—the videos complicate reading the vocalizations of “Sandcastles” or “Rocket” Beyoncé as “real” or “authentic” expressions of jilted angst or coital ecstasy. Instead of reinforcing a single identity—Beyoncé the singer/songwriter, singing her “authentic” feelings about a real situation in a direct communication via the song, something that is then reinforced via a realistic visual narrative in a video, we are presented with the appropriate scenario for that—and then are confronted with a reminder of the constructedness of these vocalizations, the ways in which they are not just unmediated expressions of Beyoncé’s real experiences. But what I find fascinating is that this doesn’t necessarily decrease the power of these vocalizations. Instead of hearing them as real in a straightforward, collapsible pop music reality extending from singer to listener via song, we encounter evidence of a more complicated, confounding reality—Beyoncé’s vocal virtuosity, which we might incorporate into our own bodies sympathetically, erotically, is evidence of work, of labor and virtuosic authority , not just of her unfiltered emotional or bodily expression.

In his work on black female performance artists, Uri McMillan suggests that such performers’ ambiguous status as both real persons and theatrical representations of themselves serves “as an elastic means to create new racial and gender epistemologies.”9 In the videos I’ve discussed above, Beyoncé performs herself-as-musician, draws attention to this performance, and, through exactly this re-focusing, makes herself less immediately available to her viewers and fans. I’m aware that can’t access her pain at the betrayal of her marital relationship, can’t access her body in sex—instead I’m confronted by her voice as at once a gateway and an obstacle, a reminder of herself as an artist. I experience what Steven Shaviro theorizes as “allure,” an obsessive awareness of a figure’ s distance from me, “the way that it baffles all my efforts to enter into any sort of relation with it.”10

As I mentioned above, Robin James and Regina Bradley have both suggested ways in which sound might trouble visual information in music video, offering a route through which black female performers can evade or undercut stereotyped roles or objectification. My reading of “Sandcastles” suggests ways in which sound and visual narrative might trouble each other; breaks or excess in Beyoncé’s voice might evidence emotional or bodily expression, but, via the video, might also be read as evidence of her hard work, her authority as a performer and songwriter. Lapses in vocal control are reframed, almost paradoxically, as in fact highly controlled, highly premeditated utterances. Beyoncé, we viewers are reminded, has precisely authored these sonic lapses—when we take them into our own bodies, replay them in our throats and chests and mouths and soft palates, we don’t have to be out of control—or not just out of control. We can choose to have these sounds become part of our bodies, to emanate from our bodies. We can elect to sound this pleasure, or to construct and construe pleasure in moments and sites of emotional pain and distress.

Fred Moten speaks and writes virtuosically about breaks, cracks, cuts—when he attends to the voice of Billie Holiday on vinyl, he suggests that:

The lady in satin uses the crack in the voice, extremity of the instrument, willingness to fail reconfigured as a willingness to go past.11

This is the kind of orchestrated failure that I’m hearing in “Sandcastles”—an excess that draws attention to itself as performance, that might invite a listener into Beyoncé’s and her own body through the erotic connective fluid of voice, even as it reminds that viewer of the illusion of any other kind of imagined audiovisual intimacy. Moten’s description of Holliday also includes something that I read as a direct personal caution, however:

She resists such interpretation, is constantly reversing and interrupting such analytic situations, offering and taking back that mastery, finally reaching radically around it. Therefore, motherfuckers are scared. Got to domesticate or explain the grained voice. Got to keep that strange—keeping shit under wraps even though it always echoes…Check yourself in the midst of an explanation that could only reveal the trace of what can’t be explained—both in the actions of a dark lady and in her grained voice.12

Perhaps, then, this article comprises a futile attempt to domesticate a text that’s not for me—Inna Arzumanova calls the visual album a work of “proprietary” black expression.13 Beyoncé’s voice touches me—but no matter how many times I run it through my earbuds, or try to bring it to reside in my own body—it’s not mine. Lemonade, like so much of the artist’s output, remains an alluring, carefully orchestrated sonic and visual world that doesn’t have—or need—my pale white self in it. Beyoncé’s voice captivates me; it resists my domestication.

Notes

- 1 Steven Connor, Dumbstruck: A Cultural History of Ventriloquism (Oxford University Press, 2000), 12.

- 2 Regina Bradley, “I Been On (Ratchet): Conceptualizing a Sonic Ratchet Aesthetic in Beyoncé’s ‘Bow Down,’” Red Clay Scholar (blog), 19 March 2013, http://redclayscholar.blogspot.com/2013/03/i-been-on-ratchet-conceptualizing-sonic.html.

- 3 Regina N. Bradley, “The (Magic) Upper Room: Sonic Pleasure Politics in Southern Hip Hop,” Sounding Out! 16 June 2014, https://soundstudiesblog.com/2014/06/16/the-magic-upper-room-sonic-pleasure-politics-in-southern-hip-hop/.

- 4 Robin James, “What Feels Good to Me: Extra-Verbal Vocal Sounds and Sonic Pleasure in Black Femme Pop Music,” Sounding Out! 21 June 2017, https://soundstudiesblog.com/2017/06/12/sonic-pleasure/.

- 5 Ashton Crawley, Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility (Fordham University Press, 2017). Shakira Holt, “‘I Love to Praise His Name’: Shouting as Feminine Disruption, Public Ecstasy, and Audio-Visual Pleasure,” Sounding Out! 11 June 2012, https://soundstudiesblog.com/2012/06/11/i-love-to-praise-his-name-shouting-as-feminine-disruption-public-ecstasy-and-audio-visual-pleasure/.

- 6 Connor, Dumbstruck, 10.

- 7 Francesca T. Royster, Sounding Like a No-No: Queer Sounds and Eccentric Acts in the Post-Soul Era (University of Michigan Press, 2012), 117.

- 8 Beyoncé, “‘Self-Titled’: Part 5. Honesty,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LFXJGr7sYDk#t=1m33s (accessed 16 May 2018).

- 9 Uri McMillan, Embodied Avatars: Genealogies of Black Feminist Art and Performance (New York University Press, 2015), 6.

- 10 Steven Shaviro, Post Cinematic Affect (John Hunt Publishing, 2010), 9.

- 11 Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minnesota University Press, 2003), 107.

- 12 Ibid., 104.

- 13 Inna Arzumanova, “The Culture Industry and Beyoncé’s Proprietary Blackness,” Celebrity Studies 7:3 (2016), 421–424.