American Music Review

Vol. XLVI, Issue 2, Spring 2017

By Angelina Tallaj, Guttman Community College, CUNY

In an age of globalization marked by proliferating population movements, ever-faster communication, and cultural exchanges across nations, diasporic communities strive, often through music, to maintain connection to a homeland identity. In doing so they create new styles in adapting to their new host society, and offer musical experiences that complicate the home/host binary positions. Dominican-American music, while influenced by American genres such as R&B, house, and hip hop, also features specifically Dominican Spanish lyrics and distinctive local Dominican rhythms to assure a continuity with Dominicans’ identity as Latinos or Hispanics. Dominican genres in New York, especially merengue and bachata, have become symbols of Latinidad (pan-Latino solidarity) for many migrants from Latin America precisely because they blend local and global genres of music. These genres mix rural Latin American cultural references with urban elements from New York City in ways that Spanish-speaking groups, who also experience newly fluid racial and ethnic identities away from their homeland, can identify with. Experiencing these Dominican-American genres is a way for migrants to reimagine new and more porous borders of geography, race, and history. They combine past and present, rural and urban, and home and host countries in ways that create new and more plural models of identities.

For many Dominicans, New York is just another Dominican city: we call upper Manhattan Quisqueya Heights, citing the Taíno Native Indian name for the island of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The 2010 US census estimated the Dominican-American population at 1,414,703,1 almost half living in New York City.2 In the last three decades, Dominican migrants and their culture have progressively moved from the margins to the mainstream across multiple industries, from baseball to politics to Hollywood. Dominicans are known for their beauty salons, bodegas, restaurants, and taxi companies, and now for Pulitzer prize winning novelist Junot Díaz, actress Zoe Saldaña (the main character in the 2009 film Avatar), and the recent election of Tom Pérez as the Chair of the Democratic National Committee. Yankee stadium hosts wildly popular merengue nights, which shows not only how established the Dominican community is in New York City, but how much we are identified with our music.

According to musicologist Paul Austerlitz, the arrival of merengue on the global stage can be traced to a 1967 merengue concert at Madison Square Garden with merengueros Primitivo Santos, Joseíto Mateo, and Alberto Beltrán.3 By the 1980s, merengue rivaled salsa as the preferred Latin music in the city. In recent decades, it is bachata that has surpassed other Latin music in popularity in the United States and that more effectively reflects the bicultural identity of many Dominican migrants as well as migrants from other countries of Latin America or young people born in New York from Hispanic parents. Bachata music was played for President Obama at the White House and is danced all over Europe in world competitions (see figure 1). It is important to note that both merengue and bachata became transnational in New York City before becoming popular across the world, in large part because the identity negotiations that Dominicans have gone through in the United States appeal to other migrating groups who have similar experiences and plural identifications. When New York-based merengue singer Millie Quezada sings “Volvió Juanita” or “Querido Emigrante,” she is not just addressing Dominicans, but communicating to all immigrants the experiences of alienation experienced in the host country: “You leave searching for a dream/You will find new horizons/Taking with you only memories/You swear that you will come back/ Dear immigrant/ Your homeland will wait for you.” When the popular Dominican-American bachata group Aventura sang in Spanglish, they used syntax construction understood by the youth that grew up speaking Spanish at home and English at school. I taught in Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 2014-15, and I was impressed at the degree to which my Latino students identified with Aventura. One LA-born students told me, “My family is from El Salvador, but it is bachata music that makes me feel like I belong to a larger Hispanic-American population. Aventura’s music speaks to me even when I am not Dominican.”

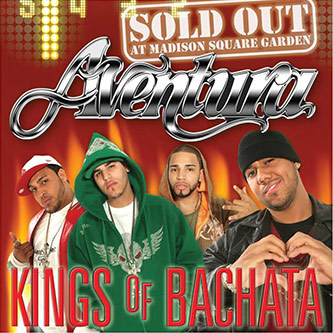

Figure 2: CD cover for Aventura’s Kings of Bachata: Sold Out at Madison Square Garden (2007). Note the hip hop fashion.

Most Dominican Americans feel primarily Dominican, but they come to also identify as American, Hispanic, and Latino. They grow up speaking Spanish at home, but English in school. Some grow up listening to Black American genres of music such as R&B and hip hop, but most are attached to the bachata and merengue of their parents. Despite a growing identification with African American culture, most migrants from Spanish-speaking countries and their descendants still prefer to identify themselves within mixed and ambiguous categories, such as Hispanic or Latinos, over mutually exclusive ones such as Black.4 As Wendy Roth stated, Dominicans (and Puerto Ricans) have “helped to create a new American racial schema moving their host society away from a dominant binary US schema—which would classify them all as White or Black, based on the one-drop rule—to a Hispanicized US schema that treat White, Black and Latino as mutually exclusive racialized groups.”5 These Latinos feel they belong to two countries, which exist in different temporalities, and feel they belong in the liminal space between black and white racial categories in the United States. Groups like Aventura have also expanded the definition of urban music in the United States to include Spanish language music, which reinforces an identity that is neither black nor white. Because of their use of R&B and hip hop influences and their similarities to African Americans in attitude and fashion styles, they get played in urban radio stations (see figures 2 and 3). However, Aventura’s appeal is not just to an “urban” music audience. Their fashion sense, traditional bachata rhythms, and vernacular language also strongly suggest a rural humble Dominican aesthetic (see figure 4).

As Stuart Hall has observed, fractured migration communities of the Global South “are not and will never be unified culturally in the old sense, because they are inevitably the products of several interlocking histories and cultures, belonging at the same time to several ‘homes’—and thus to no one particular home... They are the product of a diasporic consciousness.”6 First-generation Americans of Hispanic parents inherit this “diasporic consciousness” from their parents and struggle to navigate and negotiate their multiple cultural languages and identities, a struggle reflected in their music genres and tastes. Hall explains that the migrants’ identity “always moves into the future through a symbolic detour through the past.”7 Dominican music in New York balances tradition and innovation through mixing traditional rhythms with electronic beats and R&B vocals, Dominican slang and Spanish with English hooks, and traditional melodic riffs with rapped lyrics. These sounds and words simultaneously remind migrants of their “roots” past and enact their present cosmopolitan identities.

An early example of this fusion of styles is the Dominican-American band Proyecto Uno who has fused merengue music with techno, dancehall reggae, house, and rap since 1989 (see figure 5). They situate their music within the Dominican Republic and Dominican styles by keeping the humor, double entendres, and machismo common in Dominican music even as they use urban American beats, language, and slang. In “Brinca,” they mix traditional folk phrases such as “sana, sana, culito de rana” (heal, heal, tail of a frog) with house-influenced beats and English phrases such as “I wanna get in your pants.” In “Esta Pegao” they sing: “Nací en Nueva York, pero no me digas gringo” (I was born in New York, but do not call me gringo. See link 1). In “Latinos,” they praise the ways Latinos move the crowd and say that they will choose to be Latinos until they die (“Latinos hasta la muerte”). Each of these songs points to both the past and present identities of Latino migrants. While perhaps this initial identification with Latinos for early Dominican-American groups might have been motivated to reach a larger US market, these music genres help create new communities and identities based on the memory and pride in their past, but also in their new hybrid urban identities.

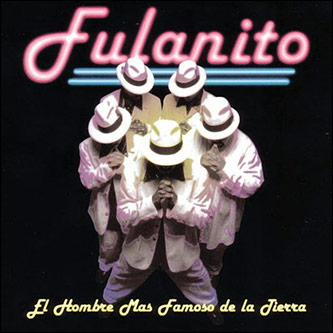

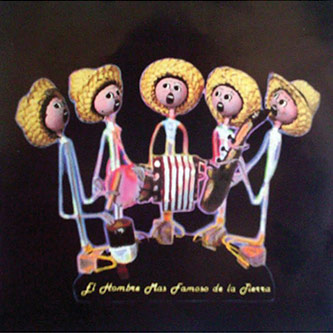

The New York-based group Fulanito, founded in 1996, looked forward and back, straddling host and home countries as they blend house and hip hop with merengue styles, especially the traditional merengue típico style. They picked a name that would only make sense to Dominicans, as it is a humorous way of saying John Doe or “what-his-name.” However, their influences were equal parts classic merengueros from the 1980s and Run DMC, and in their music, they used many traditional Dominican phrases such as “Tranquilo, Bobby, tranquilo” (Do not lose your cool Bobby) and “Ahora si es verdad que la puerca retorció el rabo” (Now it is true that the pig got her tail twisted), which served as nostalgic tropes of the homeland. This ubiquitous use of so many Dominicanism references only really happens in Dominican-American music as this kind of geographical folksiness pulls the listener back to what is specifically Dominican in their memories of a country they or their parents have left. Fulanito used the rural slang and accent of people from the Cibao region (home to merengue típico), cited areas in the Dominican Republic as well as celebrity figures such Iris Chacón and Nelson Ned that likely only Dominicans (or perhaps other Latinos) would know, paid tribute to major Dominican musical figures such as accordionist Arsenio de la Rosa, and used excerpts from famous Dominican songs as in “Cómetela Ripiá” (from Blas Durán) and “La Novela.” Like Proyecto Uno, Fulanito’s songs are also full of Dominican humor, double entendre, clever phrasing, and Dominican slang, but their music is not traditional merengue típico and instead incorporate rapping and other influences taken from their experience in the United States (see Link 2). The mix of Dominican and New York influences as the epitome of rural vs. modern perceptions is apparent in the CD cover for their 1997 production El Hombre Más Famoso de la Tierra where they appear in Run DMC attire on one side while depicting merengue típico Dominican folk figures on the other (see figures 6 and 7).

Perhaps the most well-known and popular group worldwide to come out of the New York Dominican community was the South Bronx bachata group Aventura that appeared on the scene in 2004. The group disbanded in 2011, but lead singer Romeo Santos went on to become the most followed Dominican-American artist of all time (figure 8). Romeo was the first Latin artist to headline at Yankee Stadium and filled Madison Square Garden four times in a row during 2012, making headlines in many newspapers for being more popular than Lady Gaga, Madonna, and Bruce Springsteen.8 Leila Cobo, executive director of Latin content and programming for Billboard, said that because of demographics changes in the United States where nearly a quarter of American youths are Latino, these youngsters want “musicians who grew up comfortably in a bilingual, bicultural world.”9 It is important to note that neither Aventura nor Romeo, in contrast to previous Spanish-speaking artists like Ricky Martin and Shakira, have had to crossover by singing in English, but their Spanglish and plural influences are responsible for their overwhelming popularity. Prior to Aventura there had not been a boy band that represented the new growing mixed working class youth population of the United States. Previous Latin artists such as Gloria Estefan, Ricky Martin, and Enrique Iglesias were light-skinned and presented as educated and middle or upper class. As evident in the video of Aventura’s first big hit from 2004, “Obsesión,” Aventura members are of mixed background and wore fashion styles that in the Dominican Republic are associated with the working class: twisted eyebrows, sleeveless or colorful shirts, braided or gelled hair, earrings, tattoos, and rosaries (see Link 3).

Similarly to Fulanito, Aventura (and later Romeo Santos) created eclectic music and spread bachata globally by making it a symbol of pan-ethnic Latino identity. They kept the quintessential bachata rhythm (um pa pa pa um pa um pa) and include the use of Dominican slang with words like parigüayo, holla, and mayimbe, but use harmonies, effects, and riffs from global genres such as tango (“Propuesta Indecente” by Romeo), and flamenco (“Un Beso” by Aventura). A Hip Hop influence is found in the sampling of Middle Eastern-inflected singing as a trope for female sexuality, as in “Por un Segundo” and “La Boda.” Aventura retains the traditional bachata theme of the man’s suffering through unrequited love or abandonment by a woman (e.g. “Volvió la traicionera”), but their high-register vocal quality is R&B inflected as opposed to the lower sobbing voice of traditional bachateros.10

Aventura crafted video clips in which they juxtapose references to rural Dominican Republic with New York modern scenes of fancy clubs, drinks, and cars, female models, fashionable attire, and a glamour not accessible by more traditional bachateros. When Aventura became an established group, they collaborated with wellknown urban artists such as Nina Sky and reggaetón vocalists Don Omar (“Ella y yo”) and Tego Calderón (“Envidia”). In his productions ormula Vol. 1 (2011) and Vol. 2 (2014), Romeo worked with an array of artists, and by his choices we can note his extensive list of both African American, traditional bachatero, and Latino influences. I read these productions as tributes to his multiple influences, but he makes the conscious decision to continue to sing in Spanish. He includes well-known bachateros such as Antony Santos and Luis Vargas (“Debate de 4”), well-known rappers such as Nicki Minaj (“Animales”), Drake (“Odio”), and Lil Wayne (“All Aboard”), rock figure Carlos Santana (“Necio”), R&B singers Usher (“Promise”), and salsa star Marc Anthony (“Yo también). These collaborations show how well placed Romeo is in the international music market, but also how his music is bicultural and unapologetically Latin. In the video for “Animales,” he sings in Spanish while Minaj adopts Spanglish and even craves a Dominican brand of beer: “Dame Beso/ Yo Necesito/ Dominicana/ Puerto Rico/ Sign me up where is warm/ Hace frío … Imma need a big sweet Presidente” (see Link 4). Romeo’s music is both a force of assimilation and multiculturalism that represents new directions in the American cultural and political landscape.

Aventura’s story is an immigrant story of working-class South Bronx sons of immigrants who decided to make music and went from regular jobs to successful careers. When comparing their first videos (“Obsesión,” 2004) to what Romeo Santos has recently produced (“Propuesta Indecente,” 2013), the path is one of increasing access to resources, luxury, major artists, and expensive clothing. Nevertheless, they still make aesthetic choices that align with the many sons and daughters of Latino working class in New York. Proyecto Uno, Fulanito, Aventura, and Romeo Santos all migrated to New York or were the children of working class Dominicans. Today they and their music represent the new modernity and economic power aspired to and acquired in New York at the same time that they constantly introduce details that contribute to the creation of an imaginary homeland rooted in the past and a kind of transgenerational memory. As Dominican American Osmery Fermín puts it, “Romeo’s music is something that I can share with my friends because it has verses in English. … When I hear him is like a window towards a culture which I know really well, but the distance makes you feel alienated, either because you do not live there or because you were not born there.”11 Dominican Americans like Osmery represent the new generation of Americans, que tienen un pie aquí y otro allá (who have one foot here and one there). She is clearly a New Yorker, but still feels the need to belong to the homeland of her parents. The music gives her something unique to share with her English-speaking non-Dominican friends and makes her feel less alienated from this distant and yet familiar home that she calls the Dominican Republic.

Links

- Link 1 Proyecto Uno’s “Esta Pegao”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LTg8i2E07y4

- Link 2 Fulanito’s “Guayando”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UV_BQn_kX4M

- Link 3 Aventura’s “Obsesión”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nFCprl7MawQ

- Link 4 Romeo’s “Animales” (with Nicki Minaj): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0y3-uk6oSE

Notes

- 1 U.S. Census Bureau. May 2011. The Hispanic Population: 2010. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf. Retrieved Abril 12, 2017.

- 2 Greene, Leonard, “Dominicans now Outnumber Puerto Ricans in NYC,” New York Post 13 November 2014. Accessed 14 April 2017.

- 3 Paul Austerlitz, Merengue: Dominican Music and Dominican Identity (Temple University Press, 1997), 125.

- 4 In 2012, an article from Fox News Latino reported that Dominicans were President Obama’s most enthusiastic Latino voters because they felt an affinity towards Obama’s mixed race background. (http://latino.foxnews.com/latino/politics/2012/11/02/dominicans-are-obama-most-enthusiastic-latino-voters). Accessed 12 September 2014.

- 5 Quoted in Deborah Pacini-Hernández. “Urban Bachata and Dominican Racial Identity in New York,” Cahiers d’Études Africaines 4, 216 (2014): 1031.

- 6 Stuart Hall, “Culture, Community, Nation,” Cultural Studies 7, 3 (1993), 362.

- 7 Ibid.

- 8 See “Aventura’s Huge Homestand at Madison Square,” Newsday, 13 January, 2010. Accessed 12 April 2017.

- 9 Quoted in Laura Wides-Muñoz, “Pitbull, Prince Royce, Romeo Santos and more U.S. Born Latin Artists Win Fans in Spanglish,” cnsnews.com, 26 April 2012. Accessed 12 April 2017.

- 10 Most Dominican-American bachateros navigate comfortably in the R&B and bilingual market by performing Latin-flavored R&B bilingual covers (“Stand by Me” by Ben E. King, covered by Prince Royce) although Aventura also covered well-known Latin American songs (“Lágrimas” by José José).

- 11 Osmery Fermin, interview with author, 14 April 2017.