Alumni Profile: Anthony Almojera ’21

New York City EMS Lieutenant Anthony Almojera ’21

Almojera’s book is due out in June 2022.

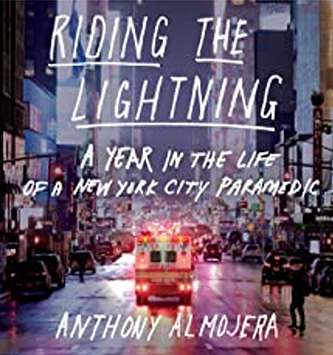

A Brooklyn College graduate who majored in political science, Anthony Almojera is an emergency medical services (EMS) lieutenant and union leader with the New York City Fire Department who has written a book about the struggles he faced on the frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic. The book, Riding the Lightning: A Year in the Life of a New York City Paramedic, will be published by Harper Collins in June of this year.

As an experienced medical technician and union leader, Almojera thought he understood the job of first responders, from dealing with traumas such as stabbings and shootings to celebrating triumphs, such as a baby born healthy on a subway platform or an elderly man in cardiac arrest brought back to life. So when a strange new virus began spreading in New York, Anthony thought that his work and training had prepared him for the new challenge. But he found in the months ahead that he was wrong, and that the virus would test the strength of the entire EMS system, one that quickly found itself at the breaking point. In his 17 years as an emergency medical provider, Almojera thought he had seen it all: “Shootings, stabbings, people on fire, you name it,” he said in a February 2021 article for The Guardian. Then came the COVID-19 pandemic. Riding the Lightning will tell the story of the EMT workers a year into the pandemic’s darkest days through Almojera’s eyes and those of New Yorkers he worked to save.

A prolific, illustrative writer, Almojera first told his story in the article “Heroes, Right?” that appeared in The Washington Post in June of 2020. By then, burnout and disillusionment had already taken their toll. He told of how the virus hit the city like a bomb, especially in the least affluent neighborhoods. It got very bad, very quickly. By mid-March, the impact of COVID-19 was quite real. “The call volume began to spike in the poorer neighborhoods,” he wrote. “The stay-at-home order in New York hadn’t even gone into effect at that point. Trump was telling us he had everything under control. The mayor was saying we had great health care, and we wouldn’t get hit as bad as other countries, so we should keep on going to the movies.”

Almojera stated in the article that it was different for the EMS workers. They were seeing what the mayor and the president were not seeing. For the frontline workers, “it was wheezing, trouble breathing, heart palpitations, cardiac arrest…I’d look at our dispatch screen sometimes and see 30 possible cardiac events happening at any one time across the city, mostly in the immigrant neighborhoods.” One day in the spring of 2020, responders took more than 5,000 calls. Before the pandemic, Almojera said it was normal to respond to one or two cardiac arrest calls per shift. “But then we came into this virus, and we weren’t bringing people back. The virus kept winning. It always ended the same way,” he said.

Effect on the Paramedics

Much of Almojera’s book deals with the weight of the fight against the virus on New York City’s paramedics. Struggling with low pay and high stress, he described how paramedics and emergency medical technicians reached a breaking point. As a union representative, he was particularly aware of the personal toll on his union brothers and sisters. Almojera wrote in the Post, “Some of us can’t stop thinking about it. I woke up this morning to about 60 new text messages from paramedics who are barely holding it together. Some are still sick with the virus. At one point we had 25 percent of EMTs in the city out sick. Others are living in their cars so they don’t risk bringing it home to their families. They’re depressed. They’re emotionally exhausted. They’re drinking too much. They’re lashing out at their kids. They’re having night terrors and panic attacks and all kinds of outbursts. I’ve got five paramedics in the ground from this virus already and a few more on ventilators. Another rookie EMT just committed suicide. He was having trouble coping with what he was seeing. He was a kid — 23 years old. He won’t be the last. I have medics who come to me every day and say, ‘Is this PTSD I’m feeling?’ But technically PTSD comes after the trauma. It’s not normal to see the things that we see.”

As a union officer, Almojera was also concerned with the inequality of pay and recognition afforded the EMS workers compared to firefighters and police. In an article in The Guardian in February 2021, Almojera stressed the burnout of paramedics struggling with low pay and high stress, especially with the low pay they receive compared to other first responders—particularly firefighters with whom they work closely. But the low pay of EMS workers leads to long hours at second and sometimes third jobs. Almojera has colleagues who drive for Uber, deliver for GrubHub. and stock grocery shelves on the side. Union leaders see a racial component to pay disparities within the FDNY. Firefighters—77 percent of whom are white—who have five years on the job can make more than $100,000, including overtime and holiday pay, whereas paramedics and EMTs, the overwhelming majority of whom are people of color, cap out at $65,000 and $50,000, respectively. “My counterpart fire lieutenants make almost $40,000 more than me,” said Almojera in The Guardian. “I’ve delivered 15 babies. I’ve been covered head to toe in blood. I mean, what do you pay for that? You can at least pay us like the other 911 agencies.”

Anthony Almojera in front of his firehouse.

The Lasting Impact of the Virus

Though waning since early 2022, the virus is still a present danger in New York City. Almojera warned of this in an October 2021 article for The.Ink. “We just had 20,000-some people die in this city, and already the crowds are lining back up outside restaurants and jamming into bars. This virus is still out there. We respond to 911 calls for COVID every day. I’ve been on the scene at more than 200 of these deaths — trying to revive people, consoling their families — but you can’t even be bothered to stay six feet apart and wear a mask, because why?”

The first year of the pandemic exacted an emotional toll on a stressed workforce. Three of the FDNY’s EMS workers died by suicide in 2020. John Mondello Jr., 23, a recent EMS academy graduate, died in April. Matthew Keene, 38, a nine-year veteran, died that June. Brandon Dorsa, 36, who had struggled with injuries from a 2015 workplace accident, followed in July. Family and colleagues told local news outlets that Mondello and Keene were struggling with trauma due to the pandemic. Almojera said he had seen more death since the start of the pandemic than in his previous decade of work. “We can’t possibly process the traumas because we’re still in the trauma,” he told The Guardian.

Almojera has been representing his union in talks with the city to renegotiate EMS and paramedic contracts. He said he hopes that city officials will think of the hardships he and his fellow first responders endured over the past year when they come to the negotiating table to discuss pay raises. But early talks have not been encouraging. “After all the sacrifices made by our members,” he said. “I don’t know whether to be angry, flip the table, or just shrug my shoulders and give up.”