Associate Professor Stephen Chester Helps Answer: When Did Our Extinct Mammal Relatives Start to Get So Smart?

April 1, 2022

Renowned paleontologist joins international team that studied the fossil record to understand mammal brain evolution.

Stephen Chester holds 3D prints of fossil primate skulls and their reconstructed brain endocasts that were included in the collaborative study recently published in Science magazine. The background image includes fossils discovered in Colorado and published by Chester and colleagues in Science magazine in 2019, and some of these fossils were also included in the study published on Thursday.

When Associate Professor of Anthropology and renowned paleontologist Stephen Chester was part of a collaborative, groundbreaking study in 2019 that used rare fossils from the Denver Basin in Colorado Springs to demonstrate how mammal body size increased after the major extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, he didn’t realize there would be such a heady follow-up.

While that study—published in Science magazine in October 2019—illustrated how that time interval allowed for mammals, and later humans, to grow into dominant species physically, it didn’t address when our extinct relatives began to separate themselves intellectually.

Until now.

While it seems obvious to understand conceptually that humans have the largest brains among animals, if you were to compare the absolute size of a human brain to that of an elephant, the elephant easily wins the contest. The statement that humans have the largest brains is not necessarily inaccurate, however, because scientists often discuss brain size in relation to body mass. When it comes to relative brain size, humans, primates, and mammals more broadly have considerably larger brains than other vertebrates.

But when did the large, complex brains of mammals began to evolve?

This question has been difficult for paleontologists to answer for quite some time. While some fossil mammal skulls are known from the time of the dinosaurs, there has been a critical 10-million-year gap in the fossil record between the extinction of the dinosaurs and the appearance of several modern mammal groups. Many species of extinct mammals are known during this time, but they are mostly represented by fragmentary fossils, such as broken jaws and isolated teeth. Complete mammal skulls from this interval are extremely rare, and this has been especially true during the first million years of Earth’s recovery following the mass extinction best known for the demise of the dinosaurs.

“We had a sense of how fast mammals increased in body mass following dinosaur extinction, but changes in the size and structure of mammal brains during this time period were harder to quantify until recently, thanks to new fossil discoveries and advancements in CT scanning technology,” Chester explained.

3D virtual models to study the internal cranial anatomy of fossil skulls

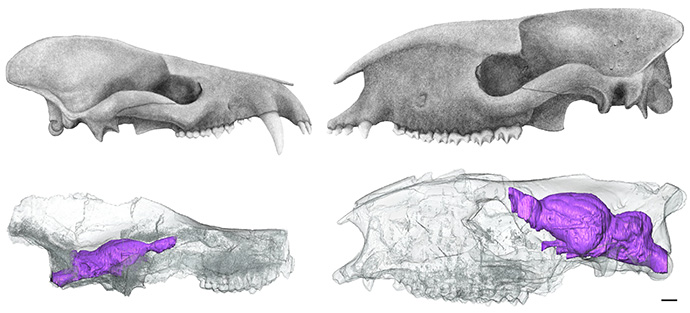

Flash forward to 2022, and Chester, who also teaches at The Graduate Center, CUNY and specializes in the early evolutionary history of primates and other placental mammals, is again part of an international group of paleontologists and other researchers who have in part used the fossil find from Colorado to understand mammal brain evolution. Findings of this work, led by Ornella Bertrand of the University of Edinburgh, were recently published in Science on March 31. This new study of more than 100 fossilized mammal skulls spanning nearly 200 million years of mammalian evolutionary history were CT scanned, and virtual brains were digitally reconstructed and measured. Body mass was also calculated for all these extinct species of mammals, and, interestingly, the results demonstrate that body size increased considerably before brain size increased in mammals following the dinosaur extinction event.

12 Arctocyon Hyrachyus translucent

In other words, instead of mammal brains gradually increasing over time, the relative size of mammal brains actually decreased following dinosaur extinction because selection favored larger body sizes while mammals were filling ecological niches in a new dinosaur-free world. It wasn’t until another 10 million years later when many groups of mammals evolved considerably larger and more specialized brains.

“Large brains are expensive to maintain and, if not necessary to acquire resources, would have probably been detrimental for the survival of early placental mammals in the chaos and upheaval after the asteroid impact,” Bertrand explained. Chester’s work in this area dates back to 2016 when he and colleague Luke Holbrook from Rowan University received funding from the National Science Foundation to CT scan mammal fossils to study their anatomy and to ultimately figure out how these ancient mammals are related to modern mammals alive today.

Chester and Holbrook CT scanned many fossil skulls, which allowed them to create 3D virtual models to study the internal cranial anatomy of these extinct mammals, including the space of the skull once filled by the brain. They were working at the American Museum of Natural History—where Chester is a research associate in the Division of Paleontology—when it became apparent that another research group led by Bertrand was in the process of studying the same specimens for a similar research project.

Discussing the collaborative nature of both projects, Chester said, “It’s common for scientists to converge on similar research questions, which, with any luck, results in large interdisciplinary collaborations that are often required to pursue comprehensive studies these days.”