Can Animals Read Minds? Research by Brooklyn College Philosophy Professor Robert Lurz Says Perhaps

Sept. 26, 2019

His work with chimpanzees and their cognitive abilities may unlock new connections between language and thought and the evolution of human thinking.

Robert Lurz, department chairperson and professor of philosophy

Understanding what other people are thinking and the ability to empathize are cognitive skills that have long been considered only the province of humans. Professor Robert Lurz, chairperson of the Philosophy Department at Brooklyn College, has been hard at work developing new ways of identifying and measuring what researchers call “perspective taking” and “theory of mind”—how much we know about what others are thinking and how we act upon that knowledge. His subjects, however, are not humans, but chimpanzees.

“Perspective taking and theory of mind develop early in humans, but when in human evolution did these abilities first arise?” says Lurz, who has taught at Brooklyn College since 2002, published dozens of articles on animal cognition and consciousness, and is the author of Mindreading Animals: The Debate About What Animals Know About Other Minds (MIT Press 2011). He works with chimpanzees because they are “our closest living evolutionary relative. If we find these abilities in great apes, it must have arisen when we had a common ancestor—about 7.5 million years ago.”

Lurz says that perspective taking and theory of mind may have proved a strategic advantage as primate populations grew over millennia. “With larger groups, you have to predict what others in the group might do,” how they might react in any given situation.

“We know that humans have such thoughts because they verbally tell us —‘I think John sees me waving at him.’ But animals don’t say things like that; so how could we ever know if they have similar kinds of thoughts?”

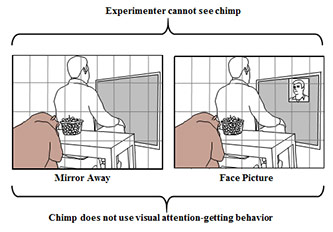

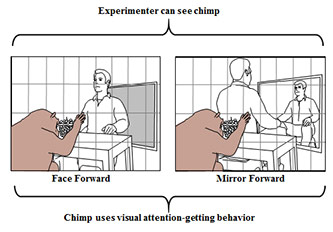

Diagrams: Chimps use visual attention-getting behaviors when and only when an experimenter can see them, even if the experimenter is not looking at them. This implies that chimps understand that the experimenter can see them in the face forward and mirror forward conditions but not in the mirror away and face picture conditions. But how would the chimp know that the experimenter could see them in the mirror forward condition? It’s possible that they deduced this from their own personal experience with mirrors: Since I can see things behind me when I looked into a mirror, so can the experimenter. This would be the first example of a nonhuman animal using its own experience to understand the experience of another, what psychologist call ‘experience projection.’

To explore this issue, Lurz set up an experiment with chimpanzees and mirrors to evaluate the communicative responses chimpanzees make to human observers. “What we found from our study was that chimpanzees produce visual gestures when and only when an experimenter sees them, even when the experimenter wasn’t looking at them. This suggests that chimpanzees, like humans, have thoughts like, ‘I think John sees me waving at him.’”

What is more, Lurz points out, chimpanzees appear to use their own prior experiences with mirrors to figure out what humans can see. They reasoned “since I can see things behind me when I look at a mirror, so can humans.” This is a sophisticated form of experience-projection or cognitive empathy, says Lurz, that has only ever been observed in humans, until now.

Lurz and his research team published their findings in a comprehensive study in the journal Animal Behavior, which has been widely cited by others engaged in similar research. He enthusiastically teaches his students that this research shows that cognition and consciousness in humans and apes share a common evolutionary origin: “It tells us a little bit more about this history of human evolution,” says Lurz.

“I regularly teach courses that have sections on theoretical issues on animal cognition and consciousness,” he says. “It is valuable to the students to see some of the research I have engaged in on this topic. In going over the research strategies and data collection processes I used in my studies, humanities students are exposed to the scientific process of hypothesis formulation and evaluation.”

For Lurz, the next frontier will be children around the age of two. “It would be interesting to test children at this age to see if they can use their own experience with mirrors to understand that someone else who is facing away from them but looking into a mirror can nevertheless see them. As far as I know, no one has ever investigated this.”