Professor Matthew Burgess Is PUMPed About His Latest Collaborative Public Art Project

Jul. 23, 2018

Led by their English teacher Natalie Nuzzo '11, '13 M.A., the eighth-grade students of David A. Boody I.S. 228 gather for the unveiling of the latest Poetry Urban Mural Project (PUMP) based on their collaborative poem, 'Where We’re From.' Time-lapse video shows how artist Josh Cochran transformed their words into images. PUMP is the vision of Brooklyn College Assistant Professor Matthew Burgess '01 M.F.A. Video by Salim Hasbini.

An upside-down rainbow. A caterpillar wearing a hat. An anthropomorphic dog jogging beside an astronaut. These are just some of the elements that make up art of the latest Poetry Urban Mural Project (PUMP), the visionary creation of Brooklyn College Department of English Assistant Professor Matthew Burgess '01 M.F.A. The vibrant mural takes up an entire wall between two doorways inside David A. Boody Intermediate School 228 in Gravesend, Brooklyn. The artist, Josh Cochran, designed it in response to poems written by eighth-grade English students taught by Natalie Nuzzo '11, '13 M.A. It is a precise example of the collaboration and conversation between literature and the visual arts that Burgess envisioned when he dreamed up the idea.

"There is a certain frequency that Josh's artwork emits when you look at it," Burgess says of the mural, the second one created through PUMP. The first, at the Elias Howe School-P.S. 51 in Manhattan, was a resounding success and made Burgess eager to continue the work at another location. "It transmits something of the energy that went into its creation."

PUMP is the culmination of Burgess's academic and artistic aspirations. It doesn't yet have a formal, repeatable structure, but he is trying to find both the time and resources to make that happen, and also get the word out about the potential of the project. Merging two passions, art and poetry, he seeks to create and transform public spaces into something that speaks to—and hopefully inspires—the larger community. And what is created is its own kind of beauty, with both a mature seriousness and a clear childlike whimsy ("serious play" is a hallmark of Burgess' teaching strategy), something that recalls the innocence of childhood even as it speaks to the realities that children in urban spaces have to regularly navigate. The latter, in particular, is a political statement that sometimes inspires criticism of the project.

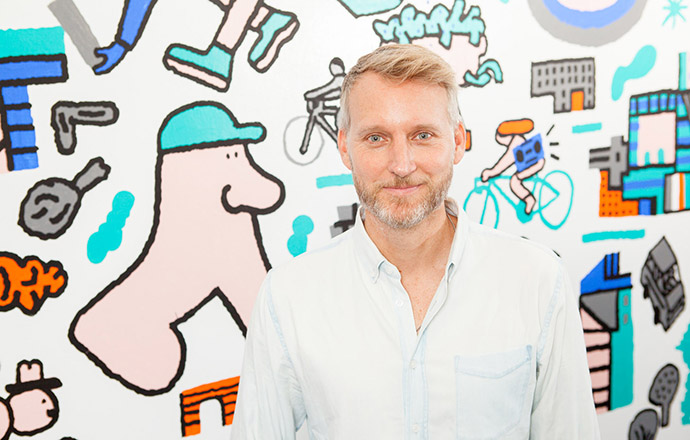

Brooklyn College Assistant Professor of English Matthew Burgess '01 M.F.A. stands in front of the work of artist and collaborator Josh Cochran, a mural that is a part of Burgess' Poetry Urban Mural Project (PUMP). Photo by Craig Stokle.

"These murals do not please everyone," Burgess says. "Transforming a blank wall into a work of art can be a political act. They make a statement about what we value. So it's not simple. Some people like walls. Our current administration likes walls. When you paint on a wall, and you paint something vibrant, colorful, exuberant, joyful, and unifying—that will irk some people. Some are interested in dividing and separating and keeping things uniform. These murals challenge that desire. They are celebrations of imagination and aliveness."

A Southern California native deeply inspired by the works of artist Keith Haring and poet E. E. Cummings, Burgess began exploring the relationship between poetry and the visual arts while taking word and image courses at Naropa University. He previously published a children's book on the life of Cummings titled, Enormous Smallness: A Story of E. E. Cummings and is currently collaborating with Josh Cochran on a picture book about the life of Haring to be released in fall 2019. He says he further developed interest in teaching poetry to young people, which he says "electrified" him, when he came to Brooklyn College and participated in programs which exposed high school students to poetry.

"I've always had these parallel interests—an ongoing question about ‘Do I want to be an artist or a writer?' And so that duality, and how the elements of this project intersect, has been in me for a long time."

At P.S. 51, students sit and contemplate PUMP's first mural project based on their collaborative poem. Photo by Matthew Burgess.

Reading the works of poet Frank O'Hara, who wrote extensively about his observations of life in New York, along with uncovering that famed poet Allen Ginsberg taught at Brooklyn College, inspired Burgess to move to the city and enroll in the college's M.F.A. program in creative writing, focusing on poetry.

"The city was calling out to me and I had friends here. So I drove across the country in my mint-green Jetta that my sister gave me and I came to New York."

In the program, Burgess got to work with some of the greatest poetic minds in the field, including Ron Padgett, Louis S. Asekoff, and Julie Agoos, while also teaching undergraduate English composition as an adjunct. He also began teaching poetry in public elementary schools through Teachers & Writers Collaborative. "I felt a sense of recognition," Burgess says about walking into his composition classroom at Brooklyn College to teach for the first time. "I was terrified, but I was also struck by how at home I felt. And I thought to myself: ‘This is my purpose.'"

In 2009, Burgess received his appointment as full-time lecturer, and he completed his doctorate in literature at the CUNY Graduate Center. He went on to teach a wide range of courses in the Department of English, including poetry writing, modern British poetry and fiction, advanced exposition, and postmodern American poetry.

The dynamic of going back and forth between teaching elementary school students and college students raised several questions for Burgess. For younger children, he discovered, writing is oftentimes an adventure, while for young adults, it can feel like a chore. Burgess sought ways in which to reignite the former's spirit of adventure in the latter.

"PUMP creates this encounter and exchange between artists and young people. The artists are individuals who have survived those challenges and obstacles to our creative development—and they've succeeded in making creativity central to their daily lives. So the kids get to meet a ‘grown up' who places enormous value on the imagination, and the artist, by meeting the kids and reading their poetry, reconnects vicariously to their own experiences as a child. They might remember where they came from, and some of that energy might find its way into the mural."

An award-winning educator, Nuzzo took what she learned from Burgess and, with the help of Burgess, Cochran, and her students, transformed the ordinary into the complex. Photo by Craig Stokle.

This approach to pedagogy had a profound effect on Natalie Nuzzo, a former student of Burgess's. Nuzzo, author of Color Is Dangerous: Equity Through Arts Based Literacy, which will be published with Peter Lang in 2019, started her academic career as a health and nutrition major, but slowly began to reconnect with her childhood desire to teach, which led her to change her area of study to English secondary education.

"I became reinterested in teaching because I had a number of great professors in the English Department," Nuzzo says. "The subject matter simply became more relevant to my goals and what I wanted to achieve to make an impact on society and to help shape young people, empower them, and help them become critical thinkers."

She says that her course with Burgess, an introduction to poetry class, was another pivotal moment in her education, reintroducing her to her love of the subject. "He exposed me to the fact that there's this conversation between art and literature—which was something I think, in my subconscious or cellular memory, I knew, but he was just so explicit and direct in saying, ‘Okay, pair a picture with this poem that you wrote. Go look for a photograph or a painting that best brings to life the ideas you are expressing in your work."

Even after she graduated with both undergraduate and graduate degrees from the college, Nuzzo and Burgess kept in touch and continued to share ideas and have conversations about these interdisciplinary notions. Out of these discussions came the idea of creating PUMP's second mural, this time at the school she had been teaching at since graduating: I.S. 228.

Nuzzo is a featured academic in PBS's 'Understanding LGBTQ+ Identity: A Toolkit for Educators,' which 'offers a series of digital media resources to help administrators, guidance counselors, and educators understand and effectively address the complex and difficult issues faced by LGBTQ students.'

Nuzzo is also an adjunct lecturer in Brooklyn College's English secondary education program. Part of the City University of New York Counseling Assistantship Program (CUNYCAP), Nuzzo worked at the college's Women's Center while enrolled as a graduate student. At the center, Nuzzo helped bring activist and poet Staceyann Chin to campus.

"To create a mural like the one we've created takes a lot of planning, coordination, and other skills that I had a bit of, but really sharpened when I worked for the Women's Center. That was where I learned the project management skills that aided me in helping to pull this together."

An award-winning educator and a PBS LearningMedia Master Teacher who recently helped the network promote its "Understanding LGBTQ+ Identity: A Toolkit for Educators," Nuzzo gathered over 20 of her students, eighth graders who essentially gave up their lunch period, to participate in the poetry exercises that would result in the collaborative poem, "Where We're From." This poem served as the starting point and inspiration for Cochran's mural design. One of the students who participated was thirteen-year-old Mahmoud Ali.

Burgess, Mamoud Ali, and Nuzzo are all smiles in front of the mural that exemplifies joint effort. Photo by Craig Stokle.

Bright-eyed, sure-footed, and hefting the weight of his backpack, Ali is a ball of infectious energy. He introduces himself with a firm handshake and some small talk about the World Cup games. He says he was rooting for the underdog Egyptian team as they represented his homeland—which he left with his family when he was five years old, but visits regularly. Mid-conversation, he darts off down the hall, and enters a classroom just across from the mural. He emerges from the classroom with a look of relief and excitement on his face.

"I got a 97!" he exclaims, pumping his fist and generously giving a pound to any extended, congratulatory fist. He had just received his score on the Math Regents Exam. He is pleased because he is interested in the STEM fields and wants to become a surgeon—or perhaps a politician; he has not yet decided for certain. It is curious, then, how a left-brained thinker might come to be interested in such a right-brained activity as PUMP.

"I kind of really like poetry because it allows you to express yourself with words that rhyme and have deep meaning to them," says Ali.

His poem, "Life in Egypt," sought to articulate the aspects of his life as a Muslim Egyptian that are often overlooked, unheard, and unseen in the larger cultural narratives.

Ali looks at the PUMP mural on the wall at his school, admiring how it interpreted the poetry he and his classmates wrote. Photo by Craig Stokle.

"Like anywhere else, there is a class system in Egypt, where the less money and resources you have, the more you suffer. Life can get really hard. But for a kid, it's relatively easy because all you have to do is go to school. Although, a school day begins at seven in the morning and ends at seven at night. So you only have time to come home eat, do homework, go to bed, and then start the whole process over again."

Ali does see a bit of his poem represented in the mural itself just in the way that it interprets the everyday as well as the aspirations of those who reside in particular urban landscapes.

"The fact that one mural can take over 20 people's different ideas and ways of seeing things, and bring it together so neatly is helpful and hopeful—helpful because it illustrates visually each of our experiences for anyone who looks at it and hopeful because it shows that even though there are so many diverse points of view, we can still find common ground."